Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition (78 page)

Read Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition Online

Authors: Colin Barrow,John A. Tracy

Tags: #Finance, #Business

You submit this budgeted cash flow from profit statement (Figure 10-3) to top management. Top management expects you to control the increases in your short-term assets and liabilities so that the actual cash flow generated by your division next year comes in on target. The cash flow from profit of your division (minus the small amount needed to increase the working cash balance held by your division for operating purposes) will be transferred to the central treasury of the business.

Capital Budgeting

This chapter focuses on profit budgeting for the coming year, and budgeting the cash flow from that profit. These two are hardcore components of business budgeting - but not the whole story. Another key element of the budgeting process is to prepare a

capital expenditures budget

for top management review and approval. A business has to take a hard look at its long-term operating assets - in particular, the capacity, condition, and efficiency of these resources - and decide whether it needs to expand and modernise its fixed assets. In most cases, a business would have to invest substantial sums of money in purchasing new fixed assets or retrofitting and upgrading its old fixed assets. These long-term investments require major cash outlays. So, a business (or each division of the business) prepares a formal list of the fixed assets to be purchased or upgraded. The money for these major outlays comes from the central treasury of the business. Accordingly, the capital expenditures budget goes to the highest levels in the organisation for review and final approval. The chief financial officer, the CEO, and the board of directors of the business go over a capital expenditure budget request with a fine-tooth comb.

At the company-wide level, the financial officers merge the profit and cash flow budgets of all divisions. The budgets submitted by one or more of the divisions may be returned for revision before final approval is given. One main concern is whether the collective total of cash flow from all the units provides enough money for the capital expenditures that have to be made during the coming year for new fixed assets - and to meet the other demands for cash, such as for cash distributions from profit. The business may have to raise more capital from debt or equity sources during the coming year to close the gap between cash flow from profit and its needs for cash. The financial officers need to be sure that any proposed capital expenditures make good business sense. We look at this in the next three sections. If the expenditure is worthwhile, they may need to raise more money to pay for it. We cover that subject in Chapter 18.

Calculating payback

The simplest way to evaluate an investment is to calculate

payback

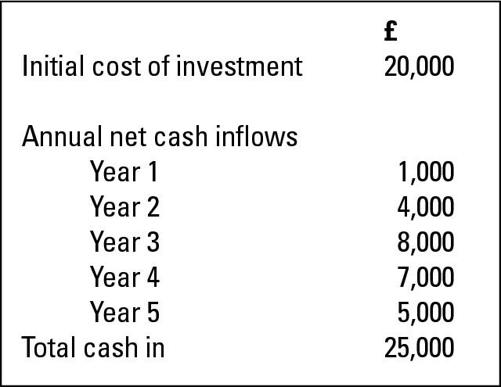

- how long it takes you to get your money back. Figure 10-4 shows an investment that calls for £20,000 cash up front in the expectation of getting £25,000 cash back over the next five years. The investment is forecasted to return a total of £20,000 by the end of year 4, so we say that this investment has a four-year payback.

Figure 10-4:

Calculating payback.

When calculating the return on long-term investments, we use cash rather than profit. This is because we need to compare like with like: Investments are paid for in cash or by committing cash, so we need to calculate the return using cash, too.

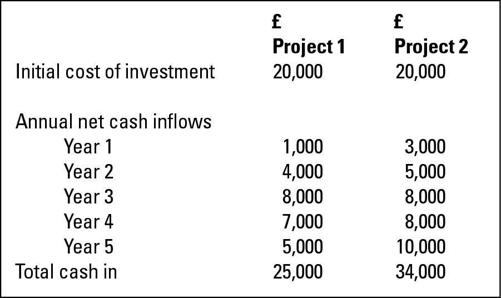

Let's suppose that we have two competing projects from which we have to choose only one. Figure 10-5 sets out the maths. Both projects have a four-year payback, in that the outlay is recovered in that period; so this technique tells us that both projects are equally acceptable, as long as we are content to recover our outlay by year 4.

However, this is only part of the story. We can see at a glance that Project 2 produces £9,000 more cash over five years than Project 1 does. We also get a lot more cash back in the first two years with that Project 2, which must be better - as well as safer for the investor. Payback fails to send those signals, but is still a popular tool because of its simplicity.

Figure 10-5:

Comparing investments using payback.

Discounting cash flow

A pound today is more valuable than a pound in one, two, or more years' time. For us to make sound investment decisions, we need to ask how much we would pay now to get a pound back at some date in the future. If we know we can earn 10 per cent interest from a bank, then we would only pay out 90p now to get that pound in one year's time. The 90p represents the

Net Present Value

(NPV) of that pound - the amount we would pay now to get the cash at some future date.

In effect what we're doing is discounting the future cash flow using a percentage that equates to the minimum return that we want to earn. The further out that return, the less we would pay now in order to get it.

The formula we use to discount the cash flow is:

Present Value (PV) = £P × 1/(1+r)n

where £P is the initial investment, r is the interest expressed as a decimal, and n is the year when the cash will flow in. (e.g in year 1 n =1, year 2 it will be 2 and so on). So if we require a 15 per cent return, we should only be prepared to pay £0.87 now to get £1 in one year's time, £0.76 for a pound in two years' time, and just £0.50 now for a pound coming in five years' time.

Take a look at Figure 10-6. If we use a discount rate of 15 per cent (which is a very average return on capital for a business) the picture doesn't look so rosy. Far from paying back in four years and producing £25,000 cash for an outlay of £20,000, Project 1 is actually paying out less money (£15,642) in real terms, allowing for the time value of money, than we have paid out.

Figure 10-6:

Comparing cash with the Net Present Value of that cash at 15 per cent discount rate.

Calculating the internal rate of return

Net Present Value is a powerful concept, though a slightly esoteric one. All we know so far about our attempt to evaluate Project 1 is that if we aim for a return of 15 per cent, our returns will be disappointing. So, we move on to the next stage in our quest for a sound way to appraise capital investment proposals - calculating exactly what the return on investment will be.

To arrive at this figure we need to calculate the actual return the project made on the discounted cash flow - the

Internal Rate of Return

(IRR). To do this, we need to find the value for ‘

r

' in the Net Present Value formula (see the section ‘Discounting cash flow') that ensures the present value of the future cash flow equals the cost of the investment. You can do this by using a guessing process of trial and error, but the easiest way to do this is to use a spreadsheet, such as the one at

www.solutionmatrix.com

(click on ‘Download Center' and ‘Download Financial Metrics Lite for Microsoft Excel') that crunches the numbers for you. In the case of Project 1, the IRR is just short of 7 per cent. You would fare little worse by leaving the money on deposit in a bank, in this case.