Untamed: The Wildest Woman in America and the Fight for Cumberland Island (19 page)

Read Untamed: The Wildest Woman in America and the Fight for Cumberland Island Online

Authors: Will Harlan

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Nonfiction, #Retail, #Top 2014

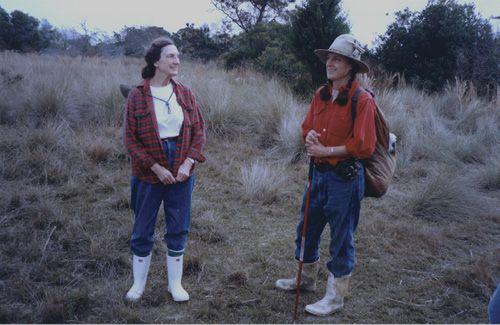

Carol and her mother, Anne (left), hike together near Lake Whitney.

BOB SHOOP

Bob Shoop collects specimens for the museum he helped build with Carol.

WILL HARLAN

Bob and Carol were pioneers in sea turtle research.

WILL HARLAN

Carol reaches inside a sea turtle carcass to examine its gut contents.

SASHA GREENSPAN

Shrimp trawlers near Cumberland often capture sea turtles in their nets.

SASHA GREENSPAN

Nuclear submarines prowl offshore and dock directly across from

Cumberland at Kings Bay.

SASHA GREENSPAN

Carol guards her wild island.

SASHA GREENSPAN

part three

shot through the heart

12

Just as foxes have dens and birds have nests, the human animal is deeply attached to home turf. Home is hardwired into us. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors had home ranges that they knew as intimately as their own bodies. They knew where water flowed out of the ground, when trees’ fruits ripened, and which plants provided medicines. Human survival—then and now—depends on our connection to our habitat. Home is the geography of life.

Home is not just shelter, nor is it simply the scenic backdrop to our lives. Places shape people.

Home

comes from the Sanskrit word

aham

, meaning self. Where we are determines who we are. It’s why we take pride in our hometowns and root for the home team.

Humans long to belong. Home is where we mesh, where we fit into place. It’s a refuge where we feel centered and connected to a larger community, where relationships root, where bonds deepen.

Modern humans are homeless and homesick, Carol believed. We didn’t know our neighbors, whether human or animal. We didn’t know where our food and water came from.

We had boxed ourselves in: we lived in climate-controlled boxes, drove fossil-fueled boxes, and worked in skyscraping stacks of boxes so we could buy boxes of food from big-box stores. But our home wasn’t a box; it was a sphere. Our lonely blue marble was the only planet we had. Our extended human family shared its home planet with our animal relatives. They were our contemporaries, Carol said. Saving wildlife was saving ourselves. We were all in this together.

To protect endangered species, the first step taken is to safeguard its critical habitat, the territory essential to its survival. Humans have critical habitat, too, Carol believed, whether a neighborhood park, backyard creek, or tree that we climbed as kids. We must go home again, she maintained, and protect the places that sustain us.

Carol’s critical habitat was Cumberland Island. Like the magnet in a sea turtle’s brain guiding her back to her birth beach, Carol had been called home to Cumberland. A homing instinct deep inside her had drawn her there.

Then suddenly the Candlers had given Carol the heave-ho. She had two weeks to pack up and leave her island home. But Carol wasn’t leaving without a fight. She knew carpentry and mechanics better than most men, and she worked cheap. Surely one of the other wealthy island families could use an extra set of hands, she reckoned. But they all turned her down, politely insinuating that they didn’t want a female custodian, especially one who ate horse.

She was thirty-six years old and stuck. Finally she had found where she fit, only to be told that she didn’t belong. She considered every possible option. Move to the mainland and buy a boat? Look for work on another nearby island? Get hired on with the National Park Service?

Then she remembered the vow she had made in her cave beside the river years ago: she would live on her own terms in an honest and original relationship with the natural world. She didn’t need a job, she realized. She needed land.

With property of her own, she could scrape up everything else. She could gather shrimp from the creeks, hunt hogs, and grow a garden. The island had plenty of freshwater springs and abundant wood for fuel and shelter. The only thing missing was the land. And no one knew land better than her new friend Louie McKee.

Louie was a surveyor who had mapped every parcel of Cumberland and owned several properties on the island. He had made a fortune in Florida real estate and was a prominent figure in Jacksonville business circles. When he learned about the National Park Service plans for Cumberland, he shrewdly purchased 126 acres, subdivided them, and sold them a year later, netting 1,400-percent profits. He kept one property for himself. Louie built a two-bedroom house on Cumberland Island’s Half Moon Bluff as a weekend vacation cottage. It was surrounded by live oaks draped in Spanish moss, and it overlooked a tributary of Christmas Creek and the north end’s amber marshes.

Carol drove down to Louie’s house in her rusted jeep—now over twenty years since she first pulled it out of a mud hole and fixed it up in her dad’s garage. Louie was drinking a scotch on the front porch, looking out across the marsh at high tide.

“Still riding that hunk of junk?” he said.

“It beats walking—though not by much.”

He offered Carol a drink. Louie was fifty years old, fair-complected, and freckled, with a slight paunch and reddish-brown hair graying at the temples. Carol joined Louie on the porch and watched the twilight stars rise out of the marsh. Inside the house, his wife Betty was being entertained by Ebby Johns, a wiry country boy who played a mean fiddle. Ebby used to work for Louie’s surveying business, but these days he spent more time with Betty. Music and laughter trickled out of the open window onto the dark porch.

“The Candlers are kicking me to the curb,” Carol said. “I have to be out by next weekend.”

“You can stay here if you want.”

“I don’t think Betty would like that.”

He glanced back at the window. “Betty and I have an understanding.”

There was a long silence. Carol felt her throat catch.

“Do you think there’s any island property still available?” she asked him.

“None that you can afford.”

“I guess I’m out of luck, then.” Carol felt the island slipping away from her. She tossed back the rest of her scotch and shook the ice against the glass. Louie poured them both another drink.

“You might be able to buy the old Trimmings house in the Settlement.”

“It’s about to collapse,” Carol said. “A sneeze would knock it over.”

“If you can keep it propped up for another year, the Park Service will buy it from you.”

Carol sat up straight in her chair.

“Do you know who owns it?”

“I can find out.”

He slipped his hand around hers. In the tar-black Cumberland night, Carol saw the lightning flash of Louie’s smile.

The next morning, Carol and Louie boated off the island and found the deed at the county courthouse. The original owner of the half-acre lot was Charlie Trimmings, a former slave who had built the shack in 1895 from boards that washed up on the beach. Now, the dilapidated house and property belonged to his grandchildren—seven brothers and sisters living in Brunswick, Georgia, about an hour north of Cumberland. Carol drove up to Brunswick that afternoon. She tracked down the address of the eldest male, Ike Trimmings, who lived in a small vinyl-sided house near the paper mill. His wife answered the door.

“What you want?” she asked, hands on her hips.

“I was hoping to speak to Ike.”

“Why a white girl want to talk to my husband for?”

Just then, Ike walked around the side of the house.

“It’s all right, Esse,” he said, smiling. “I’m Ike. Most of my kin still call me Bubba.”

“Howdy, Bubba. I’m Carol Ruckdeschel. Good to meet you.” They shook hands. Esse eyed Carol from the porch.

Bubba worked at the paper mill in Brunswick six days a week. He was in his forties, thickly built, and slightly hunched from decades of factory work, but his broad face and toothy grin radiated warmth.

“So, Miss Carol, how can I help you today?”

She breathed deeply. She felt the heft of the first thirty-six years of her life teetering on the edge of some new counterweight.

“I was wondering if your family would have any interest in selling your house on Cumberland Island.”

“That old shack?” Esse shouted from the porch. “Why would a white woman want that old shack? There must be gold buried there or somethin’.”

“No gold that I know of,” Carol said. “But the island is priceless to me. I’ve been working as a custodian there, and I’d like to have a place of my own.”

“Custodian, eh? Cleanin’ up after the rich folks?”

Carol told him about washing windows and hauling garbage for the Candlers, living with the other black caretakers, and doling out liquor to her best friend Jesse every morning. She described Jesse’s wisdom, humor, and grace, and how she had learned to cast a shrimp net from his johnboat. Bubba nodded his head and smiled.

“Miss Carol, if you were black, you could be my sister.”

“Listen, Bubba. I’ve been scraping by my whole life, working like a dog and saving up to put a roof over my head. Your house is the only one on the island that I can ever afford.”

“That shanty ain’t worth the nickel in my pocket,” Esse hollered. “I’m tellin’ ya, there must be gold under that house, Bubba.” Esse stared straight at Carol, her eyes searching Carol’s for a glimmer of doubt. Carol didn’t flinch.

“I’ll talk it over with the rest of the family,” Bubba said.

Esse was right. It wasn’t exactly gold, but that house held hidden treasure. The National Park Service was planning to buy the Trimmings shack and every other property on Cumberland. As part of the purchase deal, it would offer each of those homeowners the opportunity to live there—within a federally protected national park—for the rest of their lives.

Only a handful of Cumberland insiders knew about the National Park Service’s deals. Certainly Bubba and his family were unaware of the potential for selling their house to the park and receiving lifetime rights. But Esse suspected something, and she wasn’t going to rest until she figured out Carol’s hidden motives.

Carol didn’t rest either. She slept fitfully, fearing the worst. The Trimmings house was her last hope. All she could do was wait.

Since Carol didn’t have a telephone, she gave Louie’s phone number to Bubba. Every day for the next week, she stopped by Louie’s to borrow a tool or drop off some greens from the garden, hoping for a phone call. In the meantime, they sat on the porch or strolled down to the bluff, hanging their bare feet off the dock and watching mink swim the creek. Louie was a bright ray in her increasingly gloomy outlook.

Other than their tastes in music and alcohol, Carol and Louie had little in common, though. At heart, Louie was a city guy. Though he enjoyed fishing on Cumberland, he was an urbanite who preferred the comforts and conviviality of Jacksonville’s social scene. But he had taken a keen interest in the wilder, younger woman visiting him. While Ebby and Betty were hootin’ and hollerin’ to fiddle music, Louie and Carol began wandering off into the woods together. They soon became romantically entangled, though Carol didn’t see anything long-term developing with Louie. Louie was a welcome distraction from her worries, and, conveniently, he was also a helpful handyman with real estate know-how.

On her last day, Carol still hadn’t heard from the Trimmings family. She took a long walk on the beach to consider her options. She was prepared to move back to her animal house in Atlanta if things didn’t work out with the Trimmings’ property. She was considering Louie’s offer of staying with him for a while, too. He only came to the island for a few days at a time. She would have the place to herself while he was in Jacksonville.

Carol splashed a handful of seawater across her face and then headed back to the Candler compound to collect her belongings. Everything she owned—mostly clothes, books, and field notes—filled three boxes. She had already dug up her vegetable garden and relocated her beehive. Carol was sharpening her knives against a whetstone, preparing to butcher her chickens, when she heard Louie’s truck drive up. He rolled down the window and smiled.

“Bubba called. His family wants to meet with you tomorrow.”

Carol wore her only nice clothes—a black, loose-fitting dress and a plain white blouse she had picked up at the Salvation Army thrift store. Bubba waved from the porch and welcomed her in. All of Bubba’s sisters were gathered in the living room, talking and laughing. One of the women eased out of her chair and walked up to Carol.

“Howdy, ma’am. I’m Frances.”

“Nobody call her Frances since she was sixteen!” Bubba laughed. “Everyone just call her Sister.”

Bubba led Sister and Carol into the kitchen for a drink. On the counter was a chocolate cake that Esse had baked for Carol. The hardness in Esse’s eyes had vanished. Carol thanked her with a hug.

“I still wouldn’t sell it to you,” she whispered.

Bubba ushered Carol back into the living room, and everyone grew quiet.

“Miss Carol, we all talked it through, and we gonna sell you that property.”

Carol shook hands with Bubba.

For the first time in her life, Carol had a place to call home.

In the fall of 1978, Carol bought a wobbly shack on one-third of an acre for $36,000. Carol had saved every penny from working in Atlanta, but she was still several thousand dollars short. So her dad loaned her the money. It was also a kind of penance for his stern parenting. “I know it wasn’t always easy for you,” he told her. “I’m glad you finally found what you were looking for. At least you can’t get into any trouble out there.”

“I can get into trouble anywhere,” Carol smirked.

After the legal ink dried, Carol felt pangs of guilt about the Trimmings deal. She stayed in touch with Bubba and Esse—and with the animated elder sister, Frances. But still.

“It was devious,” Carol told her parents after signing the papers. “I feel really bad about it.”

Despite her misgivings, she was finally free. “I’m here! This is mine!” she shouted when she opened the door to her shack for the first time in 1978. She didn’t have to worry about making money or pleasing a boss. She could live off the land. She could live by her own rules.