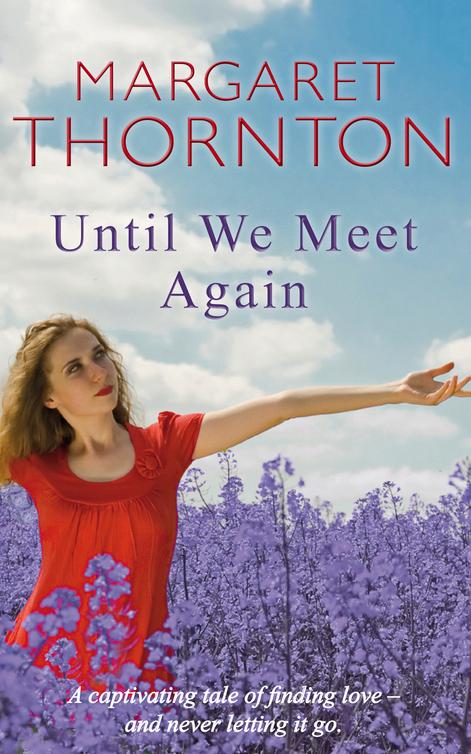

Until We Meet Again

Read Until We Meet Again Online

Authors: Margaret Thornton

M

ARGARET

T

HORNTON

Once again, for my husband, John, with my love and thanks for all his support and encouragement. And the hope that we may enjoy many more holidays in our favourite resort of Scarborough.

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-One

- Chapter Twenty-Two

- Chapter Twenty-Three

- Chapter Twenty-Four

- Chapter Twenty-Five

- Chapter Twenty-Six

- About the Author

- By Margaret Thornton

- Copyright

T

illy Moon lifted Amy out of her baby carriage, sitting her on one arm as she pointed with her other hand to the billboard. ‘See, Amy – that’s Mummy,’ she said.

Amy, aged two, couldn’t read, of course, but she was already talking well. She was as bright as a button as the saying went, and her Aunt Tilly thought the world of her.

‘Wednesday, August 5th, 1914, at 6.30 p.m. Guest appearance of Madeleine Moon, Yorkshire’s own Songbird,’ read the notice. It was advertising the special event which was to take place at one of the shows given by Uncle Percy’s Pierrots at their open air stand on the beach, in the north bay of the town.

‘Mummee…’ said the little girl, pointing and laughing as though she understood.

‘Yes, your clever mummy,’ said Tilly, kissing the child’s downy soft cheek, ‘and that – see – that’s Daddy.’

Further down the poster, in somewhat smaller letters, were the words ‘Freddie Nicholls, Conjuror Extraordinaire’. Freddie was Amy’s father, and had been married to Madeleine – who was usually known as Maddy – for four years.

‘Daddee…’ echoed the child as Tilly, finding her somewhat heavy, put her down on the ground. ‘Walk…walk’ she cried when Tilly made to lift her up and put her back in the perambulator. ‘Amy walk.’

‘Very well then, just for a little while,’ said her doting aunt.

They were a pleasant sight, the tall sandy-haired girl and the toddler, as they made their way through the gate of Peasholm Park, at the northern end of the town of Scarborough. The little girl wore a coral pink coat with a shoulder cape, made of fine woollen cloth, and her matching feather-trimmed bonnet was tied loosely beneath her chin revealing her dark curly hair, which her mother had coaxed into ringlets. Tilly’s long-sleeved cotton dress with narrow stripes of apple green and white and a large white collar suited her fair colouring and her willowy slimness; her small straw hat trimmed with matching apple green ribbon sat at a jaunty

angle atop her light gingerish hair, which she wore in the fashionable short style.

Tilly pushed the pram with one hand, holding her niece’s hand with the other one, as they walked by the side of the park lake.

‘Ducks!’ cried the little girl. ‘Quack, quack!’ A couple of the more adventurous birds came out of the water, waddling onto the path just in front of them.

‘Yes, they’ve some to say hello to us, haven’t they, darling?’ said Tilly. ‘Here we are – let’s give them a treat, shall we?’ She opened her long-handled bag, which she wore slung over one shoulder, and took out a paper bag containing stale crusts of bread. She handed a couple to the little girl, who threw them onto the ground, laughing excitedly as the ducks, joined now by two more, quacked and jostled one another in an attempt to seize the bounty.

‘There’s plenty more,’ said Tilly, scattering the remaining crusts on the path. Amy clung tightly to her hand as the birds squawked and squabbled and then, replete at last, waddled back to the lake and swam away.

‘Gone.’ said Amy. ‘Ducks all gone.’

‘Never mind,’ said Tilly. ‘We’ll come and see them again another day. And now I think we’d better be heading back.’ Aware that the child was

getting tired – three of her little steps equalled one of Tilly’s – she lifted her into the perambulator and they retraced their steps back to the gate.

Peasholm Park was a favourite haunt not only of Tilly and her niece but of all manner of folks, both young and old, and had been ever since it was first opened in 1912. As well as the lake there were leafy avenues and colourful flower-beds, even a bandstand in the centre of the lake, to which the bandsmen were rowed over to perform on summer afternoons. The park had proved to be a much needed boost to the northern end of Scarborough, known as the North Bay. More visitors were being attracted to this area now, as well as to the South Bay, on the other side of the headland, which had long been popular.

‘We’ll call and see Grandma on the way back, shall we?’ said Tilly to the little girl, who was now sitting up in her carriage with the hood pulled down, staring around her with interest. She nodded eagerly.

‘Yes, Grandma,’ she replied. ‘And Grandad Will?’

‘Yes, Grandad as well, if he’s there,’ said Tilly. She was panting just a little as she pushed the pram up the steepish slope from Peasholm Park and on to North Marine Road.

At the top end of this road, nearer to the town

centre, were the premises of William Moon and Son, Undertakers, consisting of the offices and workshop and, next door, the store which the Moon family also owned; a clothing emporium known as Moon’s Modes for all Seasons. When the store first opened in the late Victorian era it had been called Moon’s Mourning Modes, dealing exclusively in all kinds of funeral wear and requisites. This had been the era when there had been quite a cult made of mourning, following the death of Queen Victoria’s beloved husband, Prince Albert. But times had changed, and the store now sold all manner of clothing for all occasions. In charge of this establishment was Faith Moon, who was William’s wife and the mother of Tilly.

As for the undertaking business, that had been in existence since the middle years of Victoria’s reign, and had been passed down from father to son in an unbroken line. The present owners were William Moon and his son, Patrick.

William had two children: Patrick, aged twenty-eight, and Madeleine, Amy’s mother, who was twenty-four. They were the son and daughter of his first wife, Clara, who had died of pneumonia in the winter of 1900, just after the death of the old queen. His marriage to Faith Barraclough a few years later had given him four more step-children: Samuel, now twenty-eight, the same age

as his own son, Patrick; Jessica, aged twenty-four; and the seventeen-year-old twins Thomas and Matilda, who had always been known as Tommy and Tilly.

This marriage of William and Faith had caused no discord or ill-feeling amongst the off-spring of both former marriages, even though the one of Faith and Edward Barraclough had ended in divorce. Jessica, Tommy and Tilly, in fact, had agreed willingly several years ago to change their name officially to Moon. Only Samuel had proved recalcitrant; he had, in point of fact, not been asked to do so as it had been known that he would not agree. He was the only one of the four who had not become a true member of the Moon family, and the only one who had kept in close contact with his father, Edward.

Samuel, still unmarried, was a lecturer in Geology at the University of Leeds, the city in which he also resided. Jessica was now married to Arthur Newsome, a solicitor in the Scarborough firm of Newsome and Pickering started by Arthur’s grandfather. The twins, Tommy and Tilly, lived with their mother and stepfather in Victoria Avenue in the South Bay; they both still had one year to complete at their private schools near to their home.

Tilly, now on holiday from school, was spending

a good deal of her time looking after her little niece. Well, her step-niece, really, she supposed, but she had long thought of Maddy as her real sister, just as real as Jessie. She had always been devoted to Maddy ever since she had first met her back in 1900, fourteen years ago when she had been a little girl of three.

It was part of the family lore how Maddy and Jessie, both aged ten at the time, had met when they were watching a Pierrot show on the sands, the same Uncle Percy’s Pierrots, in fact, in which Maddy still took part from time to time. Jessie and Maddy had become firm friends, and thus, so had the Moon and the Barraclough families. And when William and Faith had married some years later the two girls had become sisters as well as remaining bosom friends, and Tilly had been delighted to claim Maddy as her sister as well.

Tilly stopped the perambulator outside Moon’s Modes, stopping to gaze for a little while into the plate-glass windows on either side of the door. All the women of the Moon family – Jessie, Maddy, Tilly, and Faith herself – purchased most of their clothes from the store, at reduced rates, of course. The windows were stylishly and elegantly dressed, as always. The right-hand window held what was known as leisure wear – a cycling costume, a golfing costume, and even two bathing suits with

knee-length drawers and turbans to match – and casual daytime wear; cotton dresses in the new ankle-length style, and jackets with reveres or shawl collars. Gone were the high-necked dresses and blouses made so popular by Queen Alexandra; necklines were lower and the styles were now much less stiff and formal-looking.

The other window showed bridal dresses, one in cream-coloured satin and another in white lace, ankle-length and with V-shaped necklines; and more formal evening wear in bright shades of gold, deep pink and purple, in contrast to the bridal wear. There were accessories displayed on the floor of the window; feather-trimmed hats, turbans of fine wool, and long-handled bags in suede and velvet, for day or evening wear.

Tilly lifted Amy from her carriage once again, then she pressed the latch on the glass-panelled door, hearing the musical jingle of the bell as they entered. The store was welcoming as well as being luxurious, with a deep-piled carpet in maroon and gold, and maroon velvet curtains to the cubicles where the customers could try on the articles of their choice. There had been a change in the last few years, inasmuch as they no longer stocked men’s or children’s clothing as they had done in the beginning. It had been felt that there were other stores in the town which catered very well

and exclusively for the menfolk and for children; and the women, it was found, preferred to shop at an establishment that was devoted solely to the needs of the female sex.

Faith was standing behind the mahogany counter which ran the full length of the store, at the rear. She stepped forward with a welcoming smile on seeing her daughter and granddaughter. Strictly speaking, Amy was her step-granddaughter, of course, but Faith made no distinction between Amy and her other grandchild, Gregory, the son of her daughter, Jessie, and Arthur Newsome.

Amy ran towards her with her arms outstretched. ‘Grandma!’ she cried in delight as Faith swept her up and gave her a hug. ‘I’ve been to see the ducks, an’ we gave them some bread, me and Tilly.’ It was rather difficult for the child to get her tongue round the words ‘Aunty Tilly’, but it would suffice. It would be quite a while before Amy understood the complications of their family relationships.

‘Well, that’s lovely, darling,’ said Faith. ‘Hello, Tilly. This is a nice surprise. I didn’t know you were in charge of Amy today. You didn’t say so at breakfast time.’

‘No; Maddy phoned up just after you left,’ said Tilly. ‘She has a couple of fittings to do this morning – for important clients, she said. So I was only too pleased to look after Amy for her. I’m

taking her back home soon, when I’ve said hello to Uncle Will.’ Tilly still called her stepfather by the name she had used since she was a tiny girl, even before her mother had married him.

‘He’s not here at the moment, dear,’ said Faith. ‘He’s out on a job with Katy. They’re seeing to an elderly lady who died early this morning.’ Tilly understood that the job referred to was a laying-out assignment. Katy, Patrick’s wife, often went with her father-in-law or with her husband when it was a woman who had died. Rather her than me! Tilly had often thought, but Katy was a practical, no-nonsense sort of young woman who was not easily fazed by anything. She and Patrick had been married for several years – longer than both Jessie and Maddy – but to their disappointment there were still no children.

‘Patrick’s out there, and Joe,’ Faith continued. ‘They’re quite busy, as usual.’ She gave a wry smile. ‘There’s always work to be done in this line of business, all the year round. Not as much now as in the winter, of course, but they’ll never be out of work, that’s for certain.’ She took hold of Amy’s hand. ‘Come along, Amy love. Let’s see if we can find some orange squash and a biscuit before Aunty Tilly takes you home… You can manage for a little while, can’t you, Miss Phipps?’ she called out to her assistant.

Muriel Phipps, who was completing a sale with a customer, nodded gravely. ‘Certainly, Mrs Moon.’

They did not usually address one another so formally, but they adhered to protocol whenever there were customers in the store. Muriel, who was now almost sixty years of age, had worked there for many years, from the time before Faith and William were married. When Faith took over the business she had insisted that she and Muriel should be regarded as joint manageresses. She had, in fact, benefited a good deal from the older woman’s tuition.

‘Only one biscuit, mind,’ said Tilly, as they went into the small room behind the store, where the assistants could rest for a few moments and make a cup of tea, ‘or else her mummy will say it’s spoiling her dinner.’ Faith opened the tin containing Amy’s favourite ‘choccy biccies’ and poured her a cup of orange squash.

‘All right,’ she laughed. ‘Just one. And what about you, Tilly? Would you like some orange, or a cup of tea?’

‘No, thank you,’ said Tilly. ‘I’ll get back home when I’ve returned this young lady to her mummy. I’ve left my bicycle at Maddy’s so it won’t take me long to ride back. I have some piano practice to do this afternoon… Which reminds me,’ she went

on. ‘We saw a poster advertising the Pierrot show, and Maddy’s name in big letters. It was on a billboard near to the Floral Hall. We’ll all be going, won’t we? It’s a week today.’