Vegetable Gardening (78 page)

Pac choi

No Oriental stir-fry is complete without some juicy, crunchy stalks of pac choi (

Brassica rapa

) tossed in. If you see the words bok choy, pac choi, and pak choi, they're all referring to the same vegetable. These greens feature sturdy, white, crunchy stalks and lush, large, green, flat leaves. They produce their vase-shaped, very open heads about 40 to 50 days after transplanting and, like other greens, love cool weather. Judging from their sweet, almost nutty taste, it's difficult to imagine that these plants belong to the cabbage family.

Two great varieties are ‘Mei Qing Choi', a baby-size head that only reaches 6 to 8 inches tall, and ‘Joi Choi', a standard 12- to 15-inch-tall head that tolerates hot and cold weather without bolting. ‘Violetta' and ‘Red Choi' are two varieties with attractive red coloring on their leaves.

To try your hand at pac choi, see the growing instructions for Chinese cabbage earlier in this chapter. Because it matures so quickly, pac choi can be succession planted in spring, summer, or fall in most areas (see Chapter 16 for details). However, avoid summer planting in hot climates.

Parsnips

Parsnip (

Pastinaca sativa

) is the quintessential fall root crop. I love to grow these white, carrotlike roots because, like gardeners, parsnips get sweeter with age.

As with leeks (which I discuss earlier in this chapter), you plant parsnip roots in spring and forget about them until fall. Then, after a few hard frosts, you're ready to start digging. The cold weather helps the carbohydrates in the roots turn to sugar, and boy do they get sweet! But don't yank them all in fall. In all but the extremely cold areas of the United States, parsnips can be harvested all winter right into spring (as long as the ground hasn't frozen) for a sweet spring treat. Some standard varieties to try are ‘Cobham Improved Marrow', ‘Harris Model', and ‘Andover'.

Parsnips take a long time to germinate and mature. Most varieties take 2 weeks or more to germinate and 100 to 120 days to produce roots. Luckily, they grow well in cold weather. Grow parsnips as you would carrots (see Chapter 6), but with one exception: When planting, place pairs of seeds in small holes that are 1/2 inch deep and spaced 1 inch apart, and then fill the holes with potting soil. Because parsnips may not germinate well, the second seed ensures a better germination rate. When the seedlings are 3 to 4 inches tall, thin them to one seedling per hole.

When growing root crops, especially parsnips, don't spread high-nitrogen fertilizer on the beds before planting. Soils rich in nitrogen produce hairy, forked roots.

When growing root crops, especially parsnips, don't spread high-nitrogen fertilizer on the beds before planting. Soils rich in nitrogen produce hairy, forked roots.

Peanuts

The peanut is a crop you can grow that will taste good and amaze your kids (who may have thought that peanuts only grew in ball parks and circuses). The peanut (

Arachis hypogaea

), a warm-season crop, isn't really a nut; it's actually a legume similar to peas and beans. They grow where okra and sweet potatoes thrive. They like heat and a long growing season. However, even gardeners in cold areas can have some success with peanuts, provided they start early and choose short-season varieties such as ‘Early Spanish'.

Unless you grow a field of peanuts, you probably won't get enough to make a year's supply of peanut butter, but boiled in salt water, roasted, or eaten green, fresh peanuts are a tasty and healthy snack food. (I still remember when my daughter Elena and I ate almost nothing but hot, boiled peanuts on a vacation in Georgia one winter.) Some other varieties that have big pods and more seeds per pod include ‘Tennessee Red Valencia' and ‘Virginia Jumbo'. They all need 100 to 120 days of warm weather to mature.

There are actually four different types of peanuts (runner, Virginia, Spanish, and Valencia). The first two are runner types with 2 large seeds per pod. The second two are bush types with 2 to 6 seeds per pod. Growing techniques are the same for each type.

There are actually four different types of peanuts (runner, Virginia, Spanish, and Valencia). The first two are runner types with 2 large seeds per pod. The second two are bush types with 2 to 6 seeds per pod. Growing techniques are the same for each type.

Peanuts like well-drained soil and can tolerate some drought. Plant the seeds, with the shells removed, directly in the soil after all danger of frost has passed. Space plants 1 foot apart in rows 2 to 3 feet apart. The young plant looks like a bush clover plant. Fertilize and water the plants as you would beans (see Chapter 7), but side-dress with 5-5-5 organic fertilizer when flowers appear to help with the nut formation. Yellow flowers appear within 6 weeks after planting. Hill the plants to kill weeds (see Chapter 6 for more on hilling), mulch with straw, and then watch in amazement as the fun part begins.

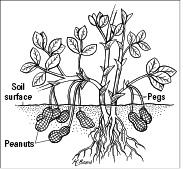

After the flowers wither, stalklike pegs emerge from the flowers and curve downward, eventually drilling 3 inches into the soil (see Figure 11-3). At the ends of these pegs, peanut shells containing the peanuts form. When the plants start yellowing, the peanuts growing underground are mature and ready to harvest. Pull the whole plant up and dry it in a warm, airy place out of direct sun; then crack open the peanut shells for a tasty treat. Most kids are fascinated by things that grow underground, and peanuts are pretty amazing in their own right, so watch your kids get wide-eyed at this underground treasure.

After the flowers wither, stalklike pegs emerge from the flowers and curve downward, eventually drilling 3 inches into the soil (see Figure 11-3). At the ends of these pegs, peanut shells containing the peanuts form. When the plants start yellowing, the peanuts growing underground are mature and ready to harvest. Pull the whole plant up and dry it in a warm, airy place out of direct sun; then crack open the peanut shells for a tasty treat. Most kids are fascinated by things that grow underground, and peanuts are pretty amazing in their own right, so watch your kids get wide-eyed at this underground treasure.

Figure 11-3:

Peanut flowers produce stalklike pegs that curve underground.

Radicchio

Radicchio (

Cichorum intybus

) is a type of leaf chicory that can be eaten as a lettuce or allowed to form a small, red, cabbagelike head. It's the latter form that people are most familiar with in salad bars and restaurants. The heads form white veins and grow to the size of grapefruits. Radicchio has a slightly bitter, tart, and tangy flavor and adds culinary and visual pizazz to salads.

For some home gardeners, radicchio isn't the easiest crop to grow, because it often doesn't form heads. Radicchio likes it cool, and it sometimes grows best in spring and sometimes in fall, depending on the variety. The following four modern varieties more consistently form heads than older varieties: ‘Palla Rossa', ‘Chioggia Red Preco No. 1', ‘Early Treviso', and ‘Indigo Hybrid'. The latter two varieties are good fall and winter selections. If you grow these four varieties at the right time, they should form heads.

In cold-winter climates, start radicchio indoors, similar to lettuce transplants, and grow it as a spring or fall crop. In mild-winter climates, it's best grown as a fall crop. Grow radicchio as you would lettuce (see Chapter 10). Most modern varieties, including those previously mentioned, form heads on their own (without being cut back) 80 to 90 days from seeding. Harvest the heads when they're solid, like small cabbages. The heads are crunchy, colorful, and good for cooking.

If plants don't start forming heads about 50 days after setting them out in the garden, cut the plants back to within 1 inch of the ground and enjoy the lettucelike greens. The new sprouts that grow will form heads.

If plants don't start forming heads about 50 days after setting them out in the garden, cut the plants back to within 1 inch of the ground and enjoy the lettucelike greens. The new sprouts that grow will form heads.

Radishes

If you're looking for quick satisfaction, grow radishes (

Raphanus sativus

). The seeds germinate within days of planting, and most varieties mature their tasty roots within 30 days. Daikon, Spanish, Chinese, and rat-tail radishes take 50 days to mature. When grown in cool weather and not stressed, radishes will have a juicy, slightly hot flavor. Of course, anyone who's grown radishes knows that if radishes are stressed by lack of water, too much heat, or competition from weeds or each other, you end up with a fire-breathing dragon that people won't tolerate. I list some popular varieties and provide tips for growing radishes in the following sections.

Varieties

Most gardeners are familiar with the spring-planted red globes or white elongated roots found in grocery stores, but exotic-looking international radishes are now showing up in specialty food stores and restaurants. These radishes require a longer season and are often planted to mature in fall or winter. (They're often called

winter radishes

for that reason.) Here are some you can try:

Japanese radishes called

Japanese radishes called

daikons

can grow up to 2-foot-long white roots.