Vera (19 page)

Authors: Robert; Vera; Hillman Wasowski

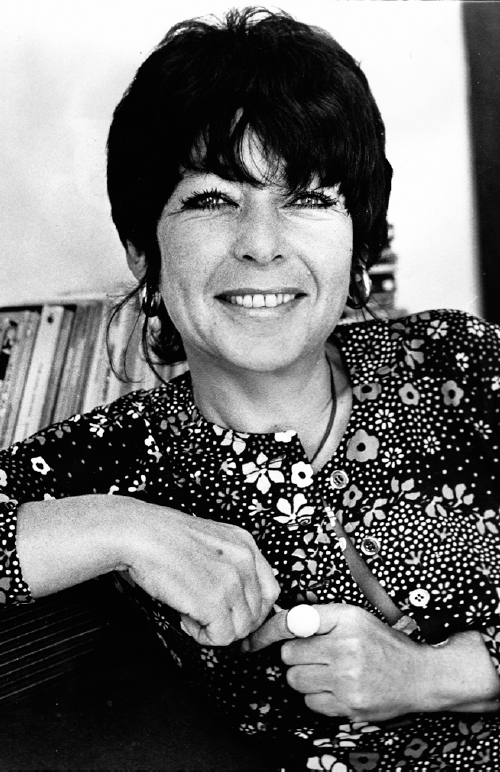

In my office at the ABC.

This Day Tonight

had just commenced. Halcyon days.

In the Loch Street house, St Kilda, supremely relaxed beneath Mirka's fresco painted on the wall in our bedroom.

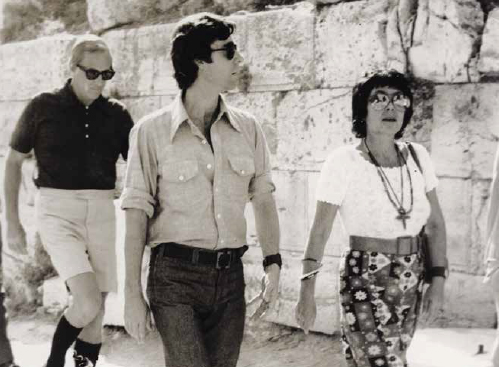

With a particularly handsome young friend in Athens, 1974. Lucky girl, Werunia.

On location for

TDT

with Peter Couchman, 1975.

With Hazel, dearest Hazel, comforting me. Why? Because I needed comforting, just as she did, at times.

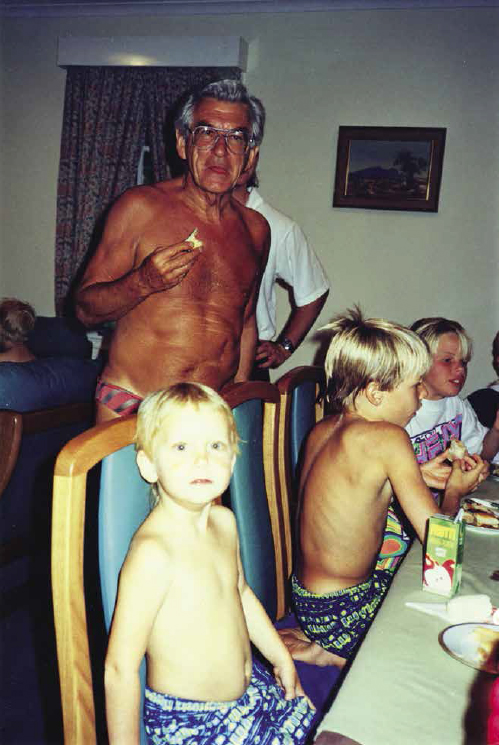

Christmas at the Lodge, in Canberra, 1990. Bob, PM, being Bob. Pani is in the foreground.

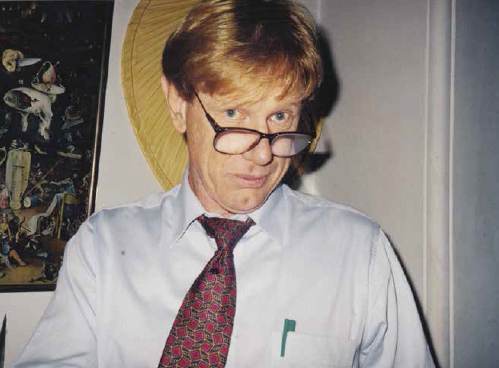

Kerry O'Brien, of course.

With Mary Delahunty in Japan, on a work trip. Mary has been my dear friend for years now. It was on the Japan jaunt that we bonded, as they say.

Twenty years at the ABC. âVera, my dear, accept this plaque in recognition of your loyal service. And Vera, my dear â love your hair.' With the ABC Chairman, and the General Manager.

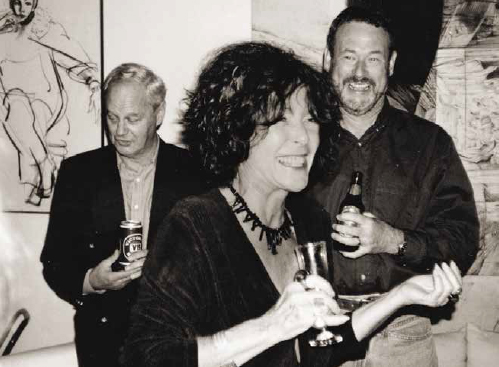

My sixtieth birthday party: I am highly delighted about something. Behind me are Peter Ross and Allan Hogan.

With Michael Leunig, 2004. A most loveable man. And witty.

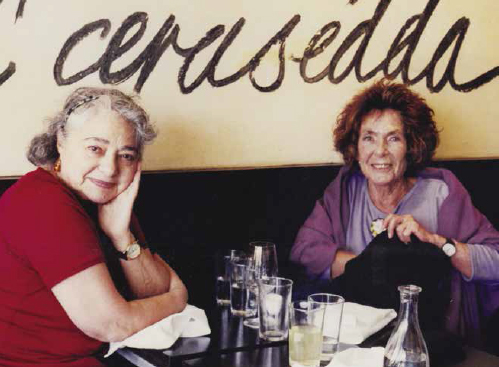

With the beloved Mirka Mora, lunch at Grossi Florentino, 2006. I'm fishing in my bag for a cigarette. I probably had been told by the nicotine nazis that smoking indoors was verboten.

Â

16

Â

ABC

M

aking costume jewellery for a living, in the way I do, can't go on forever. It's like a thousand things in life â for a while, okay, then you've had enough.

One fine day, as I'm sitting at my work table with pliers and tweezers, a voice, mine, complains loudly:

Werunia, you're driving me crazy. Do something.

Do something? Do what? Petition the government to employ me as a journalist? I have to show some initiative.

What do you think, Werunia? That the Australians are going to come to your door and say,

â

A thousand apologies, clever Vera, what were we thinking, yes, go to work at the

Age'

?

I watch television â the ABC only. The other channels, why would you? For children. I watch the news, of course. The man who reads the news each night does a fine job. I could write his news scripts: why not? I have the experience. My English is okay now; I could do it. If not news scripts, something else. Drama scripts; many other things.

I've been thinking for weeks,

Werunia, show some initiative. What's the worst that can happen?

Maybe the ABC will say, âPerhaps not.' So what? I am thick-skinned.

Actually I'm not.

But, Werunia, show some initiative.

I dress myself beautifully, take the tram down Brighton Road to Ripponlea, stroll to Gordon Street, the studios of the ABC in Victoria, and ask the commissioner in my most charming Polish-accented English to see the person, man or woman, who has the power to hire hopeful people like myself who arrive unannounced.

The commissioner, a very courteous chap, says, âYou are looking for employment?'

âYes, I am looking for employment.'

âIn what capacity, if you don't mind my asking?'

âI do not mind you asking. I am a journalist.'

âAre you indeed? A journalist? Will you object to taking a seat for a minute or two while I make a call?'

âI have no objections at all.'

In the foyer, where I wait for the commissioner to make his calls, hang portraits of ABC presenters, all in black and white, as if the fact that television is broadcast in black and white means that the presenters will only be recognisable in monochrome. There are portraits of James Dibble, Michael Charlton, and a woman with a brilliant smile who, I think, hosts a program for small children. There is also a portrait of Talbot Duckmanton, the boss of the whole thing, as far as I know.

Sitting here in the foyer, I feel a type of contentment. Warsaw comes back to me with great force, nostalgia of a sort. The people I knew when I was learning one thing and another at Warsaw Television had a better idea than the party stooges who ran the station of the potential of television. We saw it all at once and completely. We had read

1984

in Polish (in hiding) and we knew that Orwell was right to depict television as a brutish agent of totalitarian manipulation. But we saw, too, that the vigour of the new medium would surely exceed the exploitation that the party stooges imagined. It excited us in the way that a new, adored lover excites you; everything that you knew about arousal soon to be left behind, superceded. Okay, the new lover has a few gross habits that you might be forced to overlook â he picks his nose; he farts unapologetically â but dear God, what he can conjure with his hands, his lips.

This was our time. Our time. Yes, television was invented decades earlier, but real broadcast television with a full schedule of shows only got into the homes of the people after the war. On Polish television, State Television, there was a great deal of nonsense: carefully curated news and current affairs, of course, but also ludicrous comedies (Papa arrives home from work only to find that Mama has accidentally locked the family dog in the refrigerator, some such craziness), children's shows hosted by a clown with a big red nose, soap operas slanted toward socialist realism (Wladyslaw, the factory foreman, goes to Moscow to learn more about spiggots or something and falls in love with the Russian spiggot genius, Dunya, but responsibly returns to Kraków, with blueprints for a new super-spiggot). All of that silliness. We saw what it could be, and we were right, if not in Poland then in America, in England, Scandinavia. Do you think we wanted Beckett and Pinter twenty-four hours a day? No. We wanted

Checkerboard

, and

Four Corners

. We wanted Aunty Jack. We imagined original dramas, whole series that gave to the filmed script the liberty of the novel, such productions as those that Krzysztof Kieslowski was one day to provide with his

Decalogue

stories, and what American television would give us in such dramas as

Deadwood

, The

Sopranos

,

Breaking Bad

. It came. Not on this day in 1959 when I sit on a couch in the foyer of Gordon Street with my legs on show, but it came.

The commissioner has concluded his conversation on the telephone. He calls me to the desk.

âI should have asked before,' he says. âIs there anyone in particular you wish to speak to?'

âThe boss.'

âDo you have experience in anything other than journalism, by any chance?'

âSure. In drama.'

âIn drama. Good. You should perhaps see Henry Cuthbertson, the head of drama.'

âI would be happy to see Henry Cuthbertson.'

âMr Cuthbertson is at the Lonsdale Street studios. Not here at Gordon Street. Do you think you could take yourself round to Lonsdale Street?'

I say, âSure.'

And off I go, down to the tram stop and into Melbourne.

Oh, I am full of confidence. This is destiny, or something distantly related to destiny. Or not destiny at all, but just initiative. But maybe initiative

is

destiny, part of its process. Werunia, who cares? Just be charming to Henry Cuthbertson.

But Henry Cuthbertson, when I meet him an hour later, is the one who does all the charming. He is a handsome man, with one of those trained acting voices that are never heard outside cinemas and theatres anywhere in the world other than on the BBC in England and on the ABC in Australia. Voices of this sort, invariably male, could make the reading aloud of an omelette recipe sound seductive and inspiring.

Seated in his office, he faces me and says, âMay I call you Vera? I dislike formality. Please call me Henry. Your résumé is impressive, I must say. You appear to have had your fingers in an extraordinary variety of pies. But Miss Wasowski' â he knew to pronounce the âW's as âV's â âVera, I don't know if we can accommodate you in Drama. And yet, I have a suggestion. I'm going to send you back to Gordon Street to meet our Ada Jacobi, a wonderful woman, in charge of make-up, and from Poland, like you. What I'm anticipating is this: that you think of coming to work for us in make-up, pending Ada's approval. Tell me what you think.'

What did I think? After listening to his gorgeous voice, enjoying his gorgeous manners? He could have told me that he wanted me to empty the ashtrays in Gordon Street and I would have felt flattered.

I return by tram to Gordon Street to meet my compatriot, Ada Jacobi. Henry has phoned ahead. Ada is very like me in certain ways; she has a theatrical background. I sit in a chair in the make-up studio, with Ada in another chair, leaning towards me. She is studying my own make-up, and appears to be impressed. We talk in Polish and in English.

After a half hour of chatter about politics, theatre and television in Poland, she says, âYou come and work for the ABC. Of course in makeup, but who knows? Other chances will come your way. Positions come up. They like to recruit inside the tribe.'

I'm back on the tram for the fourth time that day. And you know, it's a beautiful day, it's the Australian spring. Along Brighton Road, the London Planes are coming into leaf. I get off at Carlisle Street and walk down to Fitzroy Street, my soul singing.

Clever girl, Werunia! Clever girl to go to the ABC and show off your brain and your pretty face.

It is the character side of make-up that I most enjoy. People are led into the studio hungering for the beauty they have never known, but believe they deserve. âMake me ten years younger and ten times more lovely!' â that is what they wish to say. What they really say, often, is this, and they say it in a murmur, just between the woman in the chair and me: âCan you do something for this poor, abused complexion, Vera dear? Say yes, for God's sake! I look like the mother of Dracula.'

And I say, âMy dear, when I am done with you, boys of eighteen will write you sonnets and beg you to send them your knickers.'

Or they say, âVera, my darling, does wardrobe have a scarf for my neck? I can't show these wrinkles! Dear God, can you help me? Also the crow's feet, make them go away!'

The men say, âI can't submit to this. Let them take me warts and all. I'm a mess, I admit it, but what would you expect after a litre of scotch and sixty cigarettes a day? No, no, I refuse to play the peacock!'

While they complain, I am at work smoothing out the furrows, exciting some colour in the sallow cheeks. I say, âSo you want me to stop?'

âYes! I mean no. Maybe. Okay, just a little. Make me look as young as I feel. Twenty.'

The art is one thing. Then there is the conversation. You make a judgement in a couple of seconds about the tolerance for chatter of the woman or the man in the chair, choose the subject, switch on, and â zoom! I rarely get it wrong. There is something about being ministered to by a person who is going to use all of her craft to make something glorious of your looks that brings out the urge to speak confessionally in both women and men; in women especially, of course, with their appetite for intimacy. A make-up artist works in the same space as the priest, the priestess, but saving your looks rather than your soul. A blemish disappears, a wrinkle is smoothed over, a fuzzy upper lip is all at once sheer and free of undergrowth â I am talking of women at the moment â and the gratitude of the poor, salvaged creature spills over into a story about a boy half her age who pesters her and pesters her with compliments that teeter on the brink of proposition, and of course it would be wrong, it would be grotesque, but she can't hold out for much longer.

âShould I, Vera? Oh God, he's unbelievably beautiful, and so gentle!'

Women adore confessing to another woman, the right woman, one who's discreet when it's important, full of sympathy and understanding, with all the right phrases at her disposal: âDid you, now?' And: âI know what you mean, I really do.' And: âThe exact same thing happened to my friend.' And: âOh, you poor, poor thing, poor baby!' And: âDid he? What an oaf!'

I have that knack, sure. But I also wish to amuse myself. If the person I am hovering over wants to talk about a home renovation (shall we say?), I might protest after a minute or two of colour-scheme nonsense: âEnough about Dulux. Who cares? Tell me about Don Chipp and what's-her-name.'

Men â straight men, at least â usually want to be considered frank and forthright. A senator says, âWhat do I think of Black Jack? A complete and utter bastard. Pardon my French. Don't quote me. I never said a damned thing, and I've never seen you before. But, yeah, he's a bastard.' The senator's party is in government with Jack McEwen's party.

And there are stories that unfold as serials. I hear the opening of the story one day, the continuation the next, more the next, then the crisis and the requests for advice, which I give.

âSo you are saying you're happily married. Pardon me, but a man who is happily married does not allow a woman to unzip his trousers in the back of a taxi. She can be your mistress.'

I'm like one of those magazine columnists who respond to letters from readers. And I recognise what the columnists also recognise: that nobody is going to take the advice; that she or he just wants to hear it in order to reject it then go ahead and do the catastrophic thing they really want to do.