Victoria & Abdul (17 page)

Authors: Shrabani Basu

By summer that year, the Queen had another mission on her mind. She had sensed the hostility towards the Munshi from her Household and family. Knowing that they were capable of racism, she decided that she would provide for Karim so that he was comfortable after her death. She foresaw that they would not be very kind to him after she was gone.

With this in mind, the Queen started writing the first of what was to become a volley of letters to the Viceroy, Lord Lansdowne, and to the Secretary of State for India, Lord Cross, to get a generous grant of land for the Munshi in India.

As was her style, the Queen sent a telegram, then a detailed letter, always referring to herself in the third person. She wrote to the Viceroy saying she had a request which was ‘much at heart, viz, a grant of land to her really exemplary and excellent young Munshi, Hafiz Abdul Karim, who is quite a confidential servant, – (she does not mean in a literal sense, for he is

not

a servant) – and most useful to her with papers, letters, books etc’.

3

The Queen pointed out that it was the ‘

first time in the world

’ that any native had ever held such a position and that she was anxious to mark this permanently. She felt strongly that she needed to do this as her wish to help his father, Dr Wuzeeruddin, had failed on account of his age. Promotions for other members of Karim’s family had also not been granted, despite her request, and she reminded the Viceroy that people with lesser merit had been given promotions in the past by officials who were ‘interested in them’.

The Queen wrote to the new Viceroy: ‘The Queen hopes … that this

will be done

as a mark of approbation of the Queen Empress. The Queen always rewards and promotes those who have served, or do serve her well in England, and has generally found those whom she asked to assist her in this ready to do so.’ She also asked him to call on Dr Wuzeeruddin when he visited Agra and tell him how satisfied she was with his son.

The tone of the Queen’s letter left no doubt as to her displeasure in not having been able to do anything for Wuzeeruddin or other members of Karim’s family, and the fact that she expected the Viceroy to co-operate fully. As was her habit, the letter was severely underlined. She would also refer to herself as the ‘Queen Empress’ whenever she wanted to make it clear that her command had to be followed. The letter, written on Windsor notepaper on 11 July 1890, would have been blotted approvingly by Karim. The Queen also mentioned her wish to the Secretary of State, Lord Cross, who conveyed the request to Lord Lansdowne in Calcutta.

The Viceroy was uneasy with the request as there was no precedence for a land grant of this sort for an Indian attendant. He made enquiries with the Governor of the North-West Provinces, Auckland Colvin, who informed him that local government had no power to make land grants. Gifts of land were only made very occasionally for recognition of a very long and meritorious military service. Karim did not qualify on military grounds, besides he had served for only a year. The Viceroy wrote cautiously to the Queen explaining his reservations that ‘under ordinary circumstances a man of Abdul Karim’s age would be regarded as too young for such a reward’. The Viceroy pointed out that the Munshi’s father had been transferred from one appointment to another and that an appointment had also been given to his brother, Hafiz Abdul Aziz, in recognition of the Queen’s approval of Abdul Karim’s services. He would, however, if the Queen wished, take the necessary steps for the land grant. The Viceroy suggested a grant of land that would yield an annual revenue of Rs 300 to the government and probably double that to the grantee. It was the equivalent amount given to an old soldier for exceptional service. ‘The Viceroy thinks that such a grant would be sufficient in Abdul’s case, having regarded to what would be considered proper and reasonable in his caution,’

4

he wrote.

The distance between India and Britain, and the difficulty of communication in those days, meant that letters would take fifteen to twenty days to arrive by ship and train. The Queen travelled between Windsor, Osborne and Balmoral and the Viceroy was often on tour in various regions of India, when not at his head office in Calcutta or the summer capital of the British Raj in Simla. Telegrams were inevitably quicker, but not suitable

for lengthy despatches. The business of government, nevertheless, carried on via letters and telegrams over the thousands of miles: a triangular round of letters between the India Office in Whitehall, the Viceroy’s office in India and the Queen’s various palaces. The Queen wrote practically every day, especially when driven by a particular issue. The Viceroy replied less frequently, busy as he was with the troublesome business of governing the Indian Empire.

The Viceroy, careful not to upset the Queen, said he would make a point of seeing Dr Wuzeeruddin at Agra, and ‘conveying to him the expression of your Majesty’s satisfaction with his son’.

The Queen had been spending a peaceful summer in Osborne and was not happy with the Viceroy’s letter. Once again she sensed the attempt to slight Karim’s achievements. She decided it would be best to give the Viceroy precise instructions about how much land she wanted for Karim, as she did not think his idea of Rs 300 was generous enough.

A telegram dated 1 August instructed the Viceroy: ‘Wish you to proceed with grant of land for Munshi. Think that ought not to be less than five to six hundred rupees. Position peculiar and without precedent. Father was only transferred, not promoted. Brother’s place not much promotion either. My last letter explains …’

5

A few weeks later yet another telegram reached the Viceroy, this one was from Balmoral. ‘Glad, if possible, land little more than six hundred as that so little yearly.’

6

And just in case the telegram hadn’t reached or been instructive enough, she wrote again the next day: ‘She [the Queen] sent him another telegram yesterday expressing a hope if it

were possible

to give land to the Munshi Abdul Karim worth a little more than Rs 600 as that sum brings in so little yearly.’

7

The Queen was on a roll. She was determined to give Karim what she thought he richly deserved and had little patience for the bureaucracy or the prejudice she seemed to be encountering from her Viceroy in India.

Realising that the Queen was determined to achieve her objective, Lord Lansdowne gave instructions to the officials to hunt for a plot of land for the Munshi and informed the Queen of this. He had requested that the land, if possible, ‘be not far from Agra’.

8

Over a month later, no land had been identified and the Queen was getting impatient. The letters and telegrams

were flying from Balmoral on the matter. The Queen was also pressurising the Secretary of State, Lord Cross.

The Viceroy updated the elderly Queen, delicately giving her some good news first. The good news was that John Tyler had been confirmed in his position and his appointment was to be recorded in the

North Western Provinces Gazette

dated 27 September. Lansdowne informed the Queen that it had given him ‘much pleasure’ to carry out Her Majesty’s wish in connection with this matter. With regard to Abdul Karim, however, the Viceroy did not have any positive updates.

The case of Abdul Karim is being attended to, but there is in these days v. gt. difficulty in obtaining land suitable for such a purpose. Your Majesty may rely on the Viceroy doing his best. These grants appear insignificant in amount, when judged by European standards, but in India they are

immensely prized

and given only in the most exceptional circumstances

.

9

The delay vexed the Queen further. The Munshi was to leave for India soon on holiday and she wanted the matter wrapped up urgently. On 1 October she sent a telegram to the Viceroy from Balmoral: ‘Is there chance hearing about land before 30th, when Munshi leaves for India?’ The elderly Queen’s request was proving to be a headache for the Viceroy.

The bureaucratic process of procuring vacant land was quite involved. The matter had to go from him to the Revenue Board, from the Revenue Board to the Commission, from the Commission to the Collector and from him again to the local officials, who had to enquire into and report on the land available. The Viceroy was also not sure that any land was available in the Agra area as government lands, other than waste lands, were infrequent in these provinces. He promised the Queen, nevertheless, that he would ‘expedite the matter’.

10

Apart from getting her Munshi a land grant, the Queen was also keen that his position in her Court was recognised in official circles. She made her request to Lord Cross, who had been visiting her at Balmoral, and asked him whether the India Office could recognise Karim’s appointment as her Munshi and Indian clerk. When Cross explained to her that this was not an official appointment but a personal one in her Majesty’s Household,

she wrote to him asking whether it would be possible to have it gazetted in India. She was eager for the Munshi’s position to be recorded in India as she had some concerns that Sir Auckland Colvin may not be very co-operative about the grant of land for him and therefore felt the need to make his seniority clear in Colvin’s eyes. Though the Queen was sitting thousands of miles away from India, her instinct told her that the British authorities would not be willing to give Karim a senior status unless she absolutely insisted on it. She was particularly wary of Colvin’s attitude knowing how he had tried to block Tyler’s promotion in the past.

Cross passed the request through Lansdowne saying he had informed the Queen that a gazette was an official thing and he did not see how a private appointment could be treated as official. He told the Viceroy that he could ‘make it [Karim’s position] known anyhow you think best, if you think fit to do so’.

11

The Queen was particularly sensitive to any attempt by her Household or a government official in India or Westminster to lower Karim’s position. Once, when she had learnt that the Keeper of her Privy Purse, Sir Fleetwood Edwards, had not addressed Karim as the Munshi, she was so annoyed that she wrote to Ponsonby about it. Ponsonby replied that he was surprised that Sir Fleetwood did not know that Abdul was to be called the Munshi. He said he had given the order to this effect through the house and to Major Bigge and it had been recorded in the Red Book. Ponsonby explained that perhaps Sir Fleetwood was away at the time and escaped hearing it. He said he would write to Sir Fleetwood about Abdul’s ‘proper place at the performance’.

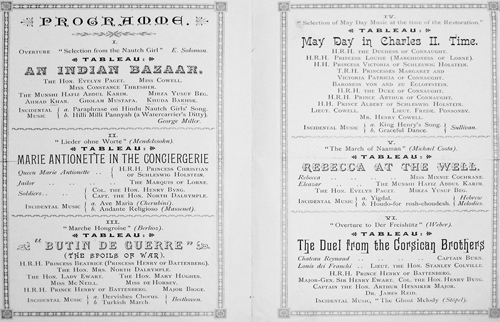

Victoria also made sure that Karim was cast in the tableaux vivant that were staged in the palaces. The roles in these tableaux were usually performed by senior members of the Household and the Royal family. That October, Karim played a major role in the tableau

Oriental Bazaar

, which was done at Balmoral in the presence of Lord Cross and many other invited guests. The Munshi helped organise the characters for the Bazaar scene and co-ordinated the costumes and sets. He chose the incidental music for the piece – an Indian folk song called

Hilli Milli Pannyah

– translated in the programme as ‘A Watercarrier’s Ditty’ and prided himself on his work. The Queen was delighted with the colourful tableau, which she praised as being ‘a really lovely and realistic scene, with such beautifully painted scenery’.

12

Karim and the Indians were also part of another tableau called

Arab Encampment

and the Queen could not have enough praise for Karim’s efforts in putting these together. Lord Cross watched in amusement.

Picture of a tableau programme.

At the same time as the Queen was writing to Lansdowne, the Viceroy and Cross were having their own private exchanges on the matter. On the delicate issue of the Queen’s request for gazetting Karim’s appointment, the Viceroy assured the Secretary of State:

I do not think we could Gazette him [Karim] to an appointment entirely unconnected with the Indian Service … but I will take steps to have it made known that AK has been duly appointed by Her Majesty, and the knowledge that he has been appointed will be sufficient to define his position satisfactorily and to prevent any misconception as to the nature of his employment.

13

He also confirmed that he would ‘take care that there is no misconception as to Abdul Karim’s status’.

14

All the negative responses from both her Viceroy and the Secretary of State to her ideas of procuring a generous land grant for Karim would not throw the Queen off course and she continuously pursued her objective over the next weeks. In October she wrote to the Viceroy that she had the highest regard for Karim and was keen to reward him. She informed him that the news of Tyler’s appointment was a relief, especially since she had been getting the sense of ‘being unable to get done what she has asked for, for nearly 3 years’.

But on the subject of ‘the grant of land for her excellent Munshi, Abdul Karim’, she was ‘a little disappointed that the grant had not yet been accomplished’, as she would have liked the matter to be settled before he left for India on leave on the 30th. However, the Munshi had told her he was ‘quite content to wait’ till it could be arranged. She informed the Viceroy that Karim would be the bearer of a letter from the Queen Empress to the Viceroy, whom he hoped to pay his respects to at Agra. ‘The Queen is very glad that he is going out in the same ship as Lady Lansdowne, and she trusts that the gales which we have had many of lately will have subsided by that time,’ she wrote.