Vimy (34 page)

Authors: Pierre Berton

Meanwhile a ration party had arrived at headquarters, and Bill Breckenridge and a fellow signaller were ordered to take the rations to the battalion’s advance headquarters beyond the crest of the ridge. It was not an enviable job. The gap between the two divisions was still open, and the German snipers were busy. The runner sent out to guide Breckenridge was suffering from shell shock, having just seen two of his friends killed by his side; he had lost his bearings and was no longer sure of his direction.

The trio set off across the shell-torn slopes, tripping over wire, sinking in mudholes to the waist, crawling over corpses. Suddenly the guide turned to the others, white-faced, and announced that he was lost. They stumbled on in the general direction of the front line, their rifles further encumbering their progress, the shrapnel and stray bullets hissing above them.

A German 5.9 shell hit twenty yards ahead, sending up a geyser of mud that showered them as it fell. Breckenridge had jumped into a shell hole to escape the blast and was now stuck fast in three feet of muck. Another shell landed beside them with a crump, piling more earth on him.

“For God’s sake,” cried Breckenridge, “pull me out and let’s beat it before we get hit!”

The other two hauled and grunted and the signaller emerged, leaving half his clothing on the barbed wire at the bottom of the hole. They ran two hundred yards to another shell hole, sat on its edge with their legs in the water, and began to laugh uncontrollably, partly out of nervousness, partly out of relief.

“She’s a great old war,” Breckenridge said. “That damn fool of a Fritz almost got us.”

“It was close enough,” his companion replied. “The mud saved our necks.”

After two hours of stumbling about the lines they finally found their advance headquarters and tossed the rations off their shoulders.

“Here are your blinking rations,” Breckenridge growled, and explained their close shave.

“That’s too bad,” said one of the headquarters men. “We’ve got all kinds of German rations here. If we’d have known we would have called and told you to remain at your H.Q.”

He waved an arm around the dugout to indicate mountains of German rations stacked in every corner. Breckenridge nodded glumly, went into the dressing station, handed the medical officer ajar of rum-the one item the Germans hadn’t left- and then headed back to his own lines.

Over on the right, Private George Johnston of the 1st CMRs was talking to a German prisoner, a former cook who’d worked in New York and spoke good English.

“I’m sorry for you,” said the German.

“Why?” asked the astonished private. “You’re going back to live in a prison camp.”

“Yes,” replied the prisoner, “but you don’t know if you’re going to get killed or not. I’m not.”

And that was all too true, for the battle was not yet over. The 4th Division had not been able to achieve its objective.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

The 4th Division

1

What had happened to the 4th Division?

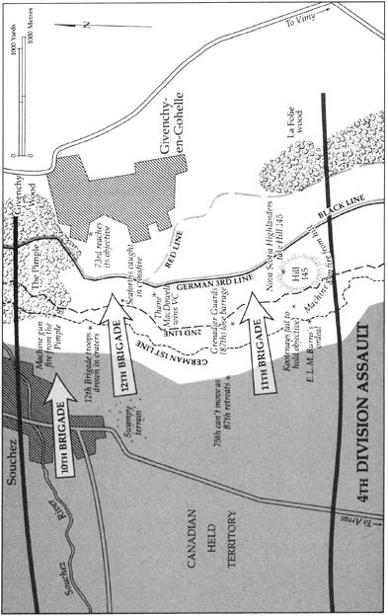

By mid-morning it had become terribly clear that the left flank of the Vimy assault was in chaos. Few of the attackers had been able to reach their objectives, and many who did had been hurled back; there were gaps all along the line. Worst of all, the fire from Hill 145, which was supposed to be seized by the battalions of Victor Odlum’s 11th Brigade, was creating havoc among the neighbouring units of the 3rd Division digging in on the ridge to the immediate right.

The planners had badly underestimated the strength of this bastion, by far the toughest and best-defended section of the ridge. Although it lay only six hundred yards from the Canadian trenches, the slope was far steeper and higher than the gentler rises to the south. The Canadian guns had not been able to blast down to the honeycomb of concrete tunnels and dugouts-the deepest on the escarpment-that sheltered the German reserves. Nor did they realize that the Germans had carefully camouflaged a network of concrete machine-gun nests on their side of the crest. These hidden guns were purposely kept out of action until the moment of the attack. Thus, the division was lured into a hail of fire.

The 4th was also the weakest division in the Corps as a result of the abortive gas raid that had left it badly mauled on March 1. That débâcle had shaken the troops. Close to seven hundred men were casualties; a dilution of green troops had reduced the fighting capacity of the division. The worst blow was the loss of so many officers. Two of the battalions chosen to make the final assault on Hill 145 had lost their commanders. In addition, they had had to replace half their officers and NCOs just five weeks before the Vimy battle.

Victor Odlum’s system of trench rotation, which made it impossible for his battalions to train as a team, may also have contributed to the anarchy that reigned on his front that cold morning. The other divisions removed entire battalions from the line for rest and training. But Odlum’s had to rehearse piecemeal because he maintained permanent battalion sectors in which smaller units were rotated. Because each battalion always had some men in the front line, its commander naturally kept his eyes focused on the front, where the danger lay, while lesser officers took over the training. Clearly, in the Canadian Corps senior officers were given a good deal of leeway, encouraged to act on their own initiative. Byng had let Currie have his way in the matter of trench raids. Watson of the 4th had let Odlum have his way in the matter of troop rotation. And Odlum let Major Harry Shaw, the acting C.O. of the Grenadier Guards (87th), have his way when he asked that the artillery leave one German trench undamaged. It was a major miscalculation.

This trench, in the very centre of the brigade front, formed part of the Germans’ second line of defence. In hindsight it seems incredible that the commander of an attacking battalion would ask the artillery to hold off. At the time, however, Shaw’s reasoning seemed to make sense. The trench was only a short distance from the Canadian line-not much more than the length of a football field; no doubt he felt his men could rush it before the Germans could recover from their surprise. The slopes facing him were steep; if the trench were destroyed by the Canadian barrage, the heaped-up rubble could form a barrier over which the men, sweating up the incline, would have to scramble. But if captured intact, it would provide instant protection from the guns on the heights above.

Whatever his reason, Shaw’s request was granted, with devastating results. In the first six minutes, the Grenadier Guards lost half their number. Of eleven officers, ten were wounded-five mortally. The fire from the undamaged trench slowed the advance; the troops, unable to maintain the timetable, lost the protection of the barrage, which leaped over the German positions. Nor did they ever regain it. Some tried to escape over to the right, only to find themselves inextricably mixed up with two other battalions. Many of the Mississauga troops-the “Jolly 75th,” who were supposed to back up the Guards-couldn’t even get out of the assembly trenches because of the pile-up in front.

Jack Quinnell, the red-headed scout who had survived the March 1 gas raid, managed to force his way over the top directly behind the Guards. “My God,” he said to himself, “there’s no barrage at all.” Ahead of him there was only mud, shell holes, and corpses. All Quinnell could see were hordes of the enemy in his path, pouring out of the galleries and passages unscathed, slaughtering the men in front of him. He jumped into a hole full of refuse and was pinned down by an explosion that half covered him with earth. He didn’t dare move because he knew that if he popped into sight he’d be a dead man. He was certainly a sick one, suffering so badly from trench mouth he could scarcely speak and so seriously from trench foot he could hardly walk. But he didn’t die. When he finally made his way to the rear he kept asking himself:

What went wrong?

As a result of this stalemate, a dangerous enemy bulge appeared in the centre of the line – the kind that every commander fears-a salient bristling with machine-gun and mortar nests that the Guards had failed to destroy. From this vantage point the Germans could pound the flanks of Odlum’s remaining troops on the Canadian right (already under fire from Hill 145) and those of the neighbouring 12th Brigade on the left, bogged down in the swamps in the teeth of a blinding snowstorm.

Now the 4th Division’s attack was divided into two separate skirmishes with the salient separating them like a knife piercing the line.

The 12th ran into trouble early, for the terrain its troops had to cross was the soggiest in the entire Vimy sector. Scores of wounded men slid into the reeking shell holes and drowned. An eerie spectacle greeted the soldiers who finally relieved the 12th the next day – dozens of corpses sitting under the water at the bottom of the great slimy craters, as if pausing for a moment to rest.

The going was so hard that some battalions could not keep up with the barrage. This left them sitting ducks for the machine guns in the salient. The 38th from Ottawa, which was closest to the German bulge, had by-passed three large craters in the confusion, all swarming with the enemy. The battalion now found itself attacked from front, flank, and rear.

It was here that Major Thane MacDowell, a darkly handsome company commander from Lachute, won the Victoria Cross. With two battalion runners beside him, MacDowell leaped forward, bombed out two machine-gun nests, then acting entirely alone chased one of the survivors down the fifty-five steps of a long tunnel. Seventy-five feet underground, in the pitch blackness, he could hear human sounds. He shouted aloud, demanding surrender, his voice echoing in the confined space, but there was no answer. MacDowell kept going, turned a corner in the tunnel, and suddenly came face to face with two German officers and seventy-seven members of the Prussian Guard.

By rights MacDowell should either have become a prisoner or a corpse at that moment. Instead, with enormous aplomb, he called back to imaginary troops as if he were at the head of a small army. At that, all the Germans raised their hands. MacDowell was in a quandary. He knew that if he were to lead all seventy-nine of the enemy up the long stairway to the top the Germans would quickly overpower him and his two runners. He solved the problem by telling them off in small groups and sending these up in a series to the runners waiting up above. The first Germans to reach the top realized they’d been bluffed. One made so bold as to reach for his rifle. That was the end of him. MacDowell had already won the DSO for a similar capture of fifty Germans earlier in the war. Now he added the purple ribbon of the V.C. to his decorations.

The Winnipeg Grenadiers, following behind MacDowell’s unit, were supposed to push on through to the next objective beyond the ridge. A few reached it but could not hold it; none returned alive. The rest of the battalion was unable to go further. By nightfall it had been reduced to two hundred disheartened men out of a total strength of seven hundred.

Stewart McPherson Scott, a subaltern with the Winnipeggers, was totally confused. He sat in a big shell hole all day long, gathering together the wounded as best he could. He had no idea where his battalion had got to. He was being harassed by his own artillery but had no way of letting the gunners know that their shells were falling short – the snow was too thick for his flares to be seen. And he had no way of getting word back to find out where the other companies and platoons might be.

Scott bound up the wounded who crouched with him in the shell hole; then, when dusk fell, he moved back a little where he found a confused mêlée of men from three battalions all mixed up together. Scott summoned the most reliable of the NCOs and did his best to straighten things out and hook up with the flanking units. For the next four days he stayed in the front line.

The other leading battalion of the 12th Brigade, the Sea-forth Highlanders from Vancouver, was as badly off as its neighbours in the maze of shell holes and obliterated trenches. Under fire from the Pimple on their left and from the German salient on the right, they had lost all sense of direction. They too failed to reach their objective. By nightfall the battalion had only sixty men who were not killed or wounded. Of the thirteen officers, eleven were casualties. The Germans never let up. Harry Bond, a stretcher-bearer with the Seaforths, had the unnerving experience of trying to carry a wounded man back through the fire on a stretcher. Before he could reach his own lines a sniper had shot the wounded man through both hands.

Of the four battalions in the 12th Brigade, only the 73rd reached its objective that morning with minimal losses, thanks to the protective presence of the 10th Brigade, acting as an anchor between the Canadians and the British on their left. The 10th had orders not to move until the other two brigades seized their objectives. Its job was to take the Pimple on the following day. But the discouraging events of Easter Monday had postponed that plan.

2

In the other mini-battle on the right, the remaining two battalions of Odlum’s brigade, faced by the unexpectedly strong opposition from Hill 145 and the flanking fire from the German salient, quickly lost their momentum. The 102nd Battalion from Northern British Columbia, dubbed “Warden’s Warriors” after their popular C.O., managed to gain its objective half-way up the slope, but only at terrible cost. With every officer knocked out, a company sergeantmajor took over until he, too, was put out of action by wounds in the hands and stomach.