Vintage Sacks (13 page)

ISLAND HOPPING

As a child I had visual migraines, where I would have not only the classical scintillations and alterations of the visual field, but alterations in the sense of color too, which might weaken or entirely disappear for a few minutes. This experience frightened me, but tantalized me too, and made me wonder what it would be like to live in a completely colorless world, not just for a few minutes, but permanently. It was not until many years later that I got an answer, at least a partial answer, in the form of a patient, Jonathan I., a painter who had suddenly become totally colorblind following a car accident (and perhaps a stroke). He had lost color vision not through any damage to his eyes, it seemed, but through damage to the parts of the brain which “construct” the sensation of color. Indeed, he seemed to have lost the ability not only to see color, but to imagine or remember it, even to dream of it. Nevertheless, like an amnesic, he in some way remained conscious of having

lost

color, after a lifetime of chromatic vision, and complained of his world feeling impoverished, grotesque, abnormalâhis art, his food, even his wife looked “leaden” to him. Still, he could not assuage my curiosity on the allied, yet totally different, matter of what it might be like

never

to have seen color, never to have had the least sense of its primal quality, its place in the world.

The text of this selection has been edited slightly from its original form in

The

Island of the Colorblind.

Ordinary colorblindness, arising from a defect in the retinal cells, is almost always partial, and some forms are very common: red-green colorblindness occurs to some degree in one in twenty men (it is much rarer in women). But total congenital colorblindness, or achromatopsia, is surpassingly rare, affecting perhaps only one person in thirty or forty thousand. What, I wondered, would the visual world be like for those born totally colorblind? Would they, perhaps, lacking any sense of something missing, have a world no less dense and vibrant than our own? Might they even have developed heightened perceptions of visual tone and texture and movement and depth, and live in a world in some ways more intense than our own, a world of heightened realityâone that we can only glimpse echoes of in the work of the great black-and-white photographers? Might they indeed see

us

as peculiar, distracted by trivial or irrelevant aspects of the visual world, and insufficiently sensitive to its real visual essence? I could only guess, as I had never met anyone born completely colorblind.

Knowing that congenital achromatopsia is hereditary, I could not help wondering whether there might be, somewhere on the planet, an island, a village, a valley of the colorblind. When I visited Guam early in 1993, some impulse made me put this question to my friend John Steele, who has practiced neurology all over Micronesia. Unexpectedly, I received an immediate, positive answer: there

was

just such an isolate, John said, on the island of Pingelapâit was relatively close, “barely twelve hundred miles from here,” he added. Just a few days earlier, he had seen an achromatopic boy on Guam, who had journeyed there with his parents from Pingelap. “Fascinating,” he said. “Classical congenital achromatopsia, with nystagmus, and avoidance of bright lightâand the incidence on Pingelap is extraordinarily high, almost ten percent of the population.” I was intrigued by what John told me, and resolved thatâsometimeâI would come back to the South Seas and visit Pingelap.

When I returned to New York, the thought receded to the back of my mind. Then, some months later, I got a long letter from Frances Futterman, a woman in Berkeley who was herself born completely colorblind. She had read my essay on the colorblind painter and was at pains to contrast her situation with his, and to emphasize that she herself, never having known color, had no sense of loss, no sense of being chromatically defective. But congenital achromatopsia, she pointed out, involved far more than colorblindness as such. What was far more disabling was the painful hypersensitivity to light and poor visual acuity which also affect congenital achromatopes. She had grown up in a relatively shadeless part of Texas, with a constant squint, and preferred to go out only at night. She was intrigued by the notion of an island of the colorblind, and wondered if I knew of a book called

Night Vision

âone of its editors, she added, was an achromatope too, a Norwegian scientist name Knut Nordby; perhaps he could tell me more.

Knut Nordby was a physiologist and psychophysicist, I read, a vision researcher at the University of Oslo and, partly by virtue of his own condition, an expert on colorblindness. This was surely a unique, and important, combination of personal and formal knowledge; I had also sensed a warm, open quality in his brief autobiographical memoir, which forms a chapter of

Night Vision

, and this emboldened me to write to him in Norway, asking how he might feel about coming with me on a ten-thousand-mile journey, a sort of scientific adventure to Pingelap, and he replied yes, he would love to come, and could take off a few weeks in August.

I asked my friend and colleague Robert Wasserman if he would join us as well. As an ophthalmologist, Bob sees many partially colorblind people in his practice. Like myself, he had never met anyone born totally colorblind; but we had worked together on several cases involving vision, including that of the colorblind painter, Mr. I. As young doctors, we had done fellowships in neuropathology together, back in the 1960s, and I remembered him telling me then of his four-year-old son, Eric, as they drove up to Maine one summer, exclaiming, “Look at the beautiful orange grass!” No, Bob told him, it's not orangeâ“orange” is the color of an orange. Yes, cried Eric, it's orange like an orange! This was Bob's first intimation of his son's colorblindness. Later, when he was six, Eric had painted a picture he called

The Battle of Grey Rock

, but had used pink pigment for the rock.

Bob, as I had hoped, was fascinated by the prospect of meeting Knut and voyaging to Pingelap. An ardent windsurfer and sailor, he has a passion for oceans and islands and is reconditely knowledgeable about the evolution of outrigger canoes and proas in the Pacific; he longed to see these in action, to sail one himself. Along with Knut, we would form a team, an expedition at once neurological, scientific, and romantic, to the Caroline archipelago and the island of the colorblind.

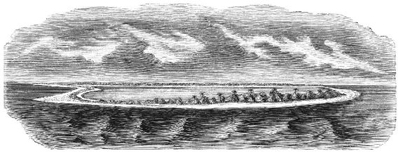

PINGELAP

Pingelap is one of eight tiny atolls scattered in the ocean around Pohnpei. Once lofty volcanic islands like Pohnpei, they are geologically much older and have eroded and subsided over millions of years, leaving only rings of coral surrounding lagoons, so that the combined area of all the atollsâAnt, Pakin, Nukuoro, Oroluk, Kapingamarangi, Mwoakil, Sapwuahfik, and Pingelapâis now no more than three square miles. Though Pingelap is one of the farthest from Pohnpei, 180 miles (of often rough seas) distant, it was settled before the other atolls, a thousand years ago, and still has the largest population, about seven hundred. There is not much commerce or communication between the islands, and only a single boat plying the route between them: the MS

Microglory

, which ferries cargo and occasional passengers, making its circuit (if wind and sea permit) five or six times a year.

The text of this selection has been edited slightly from its original form in

The

Island of the Colorblind.

Since the

Microglory

was not due to leave for another month, we chartered a tiny prop plane run by the Pacific Missionary Aviation service; it was flown by a retired commercial airliner pilot from Texas who now lived in Pohnpei. We barely managed to squeeze ourselves in, along with luggage, ophthalmoscope and various testing materials, snorkeling gear, photographic and recording equipment, and special extra supplies for the achromatopes: two hundred pairs of sunglass visors, of varying darkness and hue, plus a smaller number of infant sunglasses and shades.

The plane, specially designed for the short island run-ways, was slow, but had a reassuring, steady drone, and we flew low enough to see shoals of tuna in the water. It was an hour before we sighted the atoll of Mwoakil, and another hour before we saw the three islets of Pingelap atoll, forming a broken crescent around the lagoon.

We flew twice around the atoll to get a closer viewâa view which at first disclosed nothing but unbroken forest. It was only when we skimmed the trees, two hundred feet from the ground, that we could make out paths intersecting the forest here and there, and low houses almost hidden in the foliage.

Very suddenly, the wind roseâit had been tranquil a few minutes beforeâand the coconut palms and pandanus trees began lashing to and fro. As we made for the tiny concrete airstrip at one end, built by the occupying Japanese a half century before, a violent tailwind seized us near the ground, and almost blew us off the side of the runway. Our pilot struggled to control the skidding plane, for now, having just missed the edge of the landing strip, we were in danger of shooting off the end. By main force, and luck, he just managed to bring the plane aroundâanother six inches and we would have been in the lagoon. “You folks OK?” he asked us, and then, to himself, “Worst landing I ever had!”

Knut and Bob were ashen, the pilot tooâthey had visions of being submerged in the plane, struggling, suffocating, unable to get out; I myself felt a curious indifference, even a sense that it would be fun, romantic, to die on the reefâand then a sudden, huge wave of nausea. But even in our extremity, as the brakes screamed to halt us, I seemed to hear laughter, sounds of mirth, all around us. As we got out, still pale with shock, dozens of lithe brown children ran out of the forest, waving flowers, banana leaves, laughing, surrounding us. I could see no adults at first, and thought for a moment that Pingelap was an island of children. And in that first long moment, with the children coming out of the forest, some with their arms around each other, and the tropical luxuriance of vegetation in all directionsâthe beauty of the primitive, the human and the natural, took hold of me. I felt a wave of loveâfor the children, for the forest, for the island, for the whole scene; I had a sense of paradise, of an almost magical reality. I thought, I have arrived. I am here at last. I want to spend the rest of my life hereâand some of these beautiful children could be mine.

“Beautiful!” whispered Knut, enraptured, by my side, and then, “Look at that childâand that one, and that. . . .” I followed his glance, and now suddenly saw what I had first missed: here and there, among the rest, clusters of children who squinted, screwed up their eyes against the bright sun, and one, an older boy, with a black cloth over his head. Knut had seen them, identified them, his achromatopic brethren, the moment he stepped out of the planeâas they, clearly, spotted him the moment he stepped out, squinting, dark-glassed, by the side of the plane.

Though Knut had read the scientific literature, and though he had occasionally met other achromatopic people, this had in no way prepared him for the impact of actually finding himself surrounded by his own kind, strangers half a world away with whom he had an instant kinship. It was an odd sort of encounter which the rest of us were witnessingâpale, Nordic Knut in his Western clothes, camera around his neck, and the small brown achromatopic children of Pingelapâbut intensely moving.

44

Eager hands grabbed our luggage, while our equipment was loaded onto an improvised trolleyâan unstable contraption of rough-hewn planks on trembling bicycle wheels. There are no powered vehicles on Pingelap, no paved roads, only trodden-earth or graveled paths through the woods, all connecting, directly or indirectly, with the main drag, a broader tract with houses to either side, some tin-roofed, and some thatched with leaves. It was on this main path that we were now being taken, escorted by dozens of excited children and young adults (we had seen no one, as yet, over twenty-five or thirty).

Our arrivalâwith sleeping bags, bottled water, medical and film equipmentâwas an event almost without precedent (the island children were fascinated not so much by our cameras as by the sound boom with its woolly muff, and within a day were making their own booms out of banana stalks and coconut wool). There was a lovely festive quality to this spontaneous procession, which had no order, no program, no leader, no precedence, just a raggletaggle of wondering, gaping people (they at us, we at them and everything around us), making our way, with many stops and diversions and detours, through the forest-village of Pingelap. Little black-and-white piglets darted across our pathâunshy, but unaffectionate, unpetlike too, leading their own seemingly autonomous existence, as if the island were equally theirs. We were struck by the fact that the pigs were black and white and wondered, half seriously, if they had been specially bred for, or by, an achromatopic population.

None of us voiced this thought aloud, but our interpreter, James James, himself achromatopicâa gifted young man, who (unlike most of the islanders) had spent a considerable time off-island and been educated at the University of Guamâread our glances and said, “Our ancestors brought these pigs when they came to Pingelap a thousand years ago, as they brought the breadfruit and yams, and the myths and rituals of our people.”

Although the pigs scampered wherever there was food (they were evidently fond of bananas and rotted mangoes and coconuts), they were all, James told us, individually ownedâand, indeed, could be counted as an index of the owner's material status and prosperity. Pigs were originally a royal food, and no one but the king, the nahnmwarki, might eat them; even now they were slaughtered rarely, mostly on special ceremonial occasions.

Knut was fascinated not only by the pigs but by the richness of the vegetation, which he saw quite clearly, perhaps more clearly than the rest of us. For us, as color-normals, it was at first just a confusion of greens, whereas to Knut it was a polyphony of brightnesses, tonalities, shapes, and textures, easily identified and distinguished from each other. He mentioned this to James, who said it was the same for him, for all the achromatopes on the islandânone of them had any difficulty distinguishing the plants on the island. He thought they were helped in this, perhaps, by the basically monchrome nature of the landscape: there were a few red flowers and fruits on the island, and these, it was true, they might miss in certain lighting situationsâbut virtually all else was green.

45

“But what about bananas, let's sayâcan you distinguish the yellow from the green ones?” Bob asked.

“Not always,” James replied. “âPale green' may look the same to me as âyellow.'”

“How can you tell when a banana is ripe, then?”

James' answer was to go to banana tree, and to come back with a carefully selected, bright green banana for Bob.

Bob peeled it; it peeled easily, to his surprise. He took a small bite of it, gingerly; then devoured the rest.

“You see,” said James, “we don't just go by color. We look, we feel, we smell, we

know

âwe take everything into consideration, and you just take color!”

I had seen the general shape of Pingelap from the airâthree islets forming a broken ring around a central lagoon perhaps a mile and a half in diameter; now, walking on a narrow strip of land, with the crashing surf to one side and the tranquil lagoon only a few hundred yards to the other, I was reminded of the absolute awe that seized the early explorers who had first come upon these alien land forms, so utterly unlike anything in their experience. “It is a marvel,” wrote Pyrard de Laval in 1605, “to see each of these atolls, surrounded by a great bank of stone involving no human artifice at all.”

Cook, sailing the Pacific, was intrigued by these low atolls, and could already, in 1777, speak of the puzzlement and controversy surrounding them:

Some will have it they are the remains of large islands, that in remote times were joined and formed one continued track of land which the Sea in process of time has washed away and left only the higher grounds. . . . Others and I think . . . that they are formed from Shoals or Coral banks and of consequence increasing; and there are some who think they have been thrown up by Earth quakes.

But by the beginning of the nineteenth century it had become clear that while coral atolls might emerge in the deepest parts of the ocean, the living coral itself could not grow more than a hundred feet or so below the surface and had to have a firm foundation at this depth. Thus it was not imaginable, as Cook conceived, that sediments or corals could build up from the ocean floor.

Sir Charles Lyell, the supreme geologist of his age, postulated that atolls were the coral-encrusted rims of rising submarine volcanoes, but this seemed to require an almost impossible serendipity of innumerable volcanoes thrusting up to within fifty or eighty feet of the surface to provide a platform for the coral, without ever actually breaking the surface.

Darwin, on the Chilean coast, had experienced at first hand the huge cataclysms of earthquakes and volcanoes; these, for him, were “parts of one of the greatest phenomena to which this world is subject”ânotably, the instability, the continuous movements, the geological oscillations of the earth's crust. Images of vast risings and sinkings seized his imagination: the Andes rising thousands of feet into the air, the Pacific floor sinking thousands of feet beneath the surface. And in the context of this general vision, a specific vision came to himâthat such risings and fallings could explain the origin of oceanic islands, and their subsidence to allow the formation of coral atolls. Reversing, in a way, the Lyellian notion, he postulated that coral grew not on the summits of rising volcanoes, but on their submerging slopes; then, as the volcanic rock eventually eroded and subsided into the sea, only the coral fringes remained, forming a barrier reef. As the volcano continued to subside, new layers of coral polyps could continue to build upward, now in the characteristic atoll shape, toward the light and warmth they depended on. The development of such an atoll would require, he reckoned, at least a million years.

Darwin cited short-term evidence of this subsidenceâpalm trees and buildings, for instance, formerly on dry land, which were now under water; but he realized that conclusive proof for so slow a geologic process would be far from easy to obtain. Indeed, his theory (though accepted by many) was not confirmed until a century later, when an immense borehole was drilled through the coral of Eniwetak atoll, finally hitting volcanic rock 4,500 feet below the surface. The reef-constructing corals, for Darwin, were wonderful memorials of the subterranean oscillations of level . . . each atoll a monument over an island now lost. We may thus, like unto a geologist who had lived his ten thousand years and kept a record of the passing changes, gain some insight into the great system by which the surface of this globe has been broken up, and land and water interchanged.