Vodka Politics (27 page)

Authors: Mark Lawrence Schrad

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Europe, #General

It was up to his successor, Alexander II, to wind down the humiliating and exhausting debacle, and confront the shortcomings it had laid bare. The practical initiatives of Russia’s “great reformer” included reorganizing and modernizing the military, judiciary, and bureaucracy, and also loosening press censorship—for the first time permitting discussion about social and political challenges, including the alcohol problem. While historians commonly point to defeat in the Crimea as prompting Russia’s emancipatory reforms, the protests and riots that pitted entire swaths of Russian society against the state’s antiquated system of dual servitude through serfdom and vodka were arguably a more proximate cause. Serfdom was certainly the most obvious relic of a bygone era, but the state’s reliance on the antiquated tax farm was arguably just as important. So intertwined were the two, it was difficult to consider getting rid one fossil without the other—which is just what Alexander did.

29

Sometime between 1858 and 1860, the tsar decided that the vodka farm had to go. Beyond the perverse impact on public health and morality and the specter of an ever-widening vodka rebellion—corruption was running rampant, tax farmers were getting more brazen with their wealth, and neither the treasury nor the gentry distillers were profiting. In 1860, a report by the Department of Political Economy to the State Council openly admitted the fundamental contradiction of vodka politics:

The government cannot and must not lose sight of the effects of this system on the moral and economic welfare of the people. Everyone

knows that tax farming ruins and corrupts the people; keeps the local administration itself under a sort of “farm,” which nullifies all efforts to introduce honesty and justice to the administration; and slowly leads the government into the painful situation of having not only to cover up the flagrant breaches of the law engendered by the system, and without which it cannot operate, but even to resist the people’s own impulses to moral improvement through abstention. In this way, the government itself offers a model of disrespect for the law, support for abuse and the spreading of vice.

30

On October 26, 1860, Tsar Alexander II assented to the report and its recommendation not to renew the tax farms set to expire in 1863, at which time they would be replaced with modern system of excise taxes. Not only did this signal the end of the ancien régime in Russian finance, it also nominally removed the source of the systemic corruption (though not the deeply ingrained practices it produced) that was the lifeblood of the vodka farm and finally separated the public from the private—taxes and profits—when it came to the vodka trade. Nevertheless, the systemic corruption and dynamics of vodka politics proved to be far more resilient.

The liquor question likewise had a palpable influence on Alexander II’s other monumental reform: the abolition of serfdom in 1861. “If there have been riots for a bottle of

polugar

[cheap vodka],” asked Yakov Rostovtsev—one of the major figures in drafting the emancipation—“what will happen if we cut off a

dessiatin

[hectare] of land?”

31

While the fate of serfdom may have been determined well before the roiling liquor riots, the logistics were not. The gentry slaveholders were pressuring the Crown to protect their power by granting the serfs their release without land. The specter of a massive peasant population that was both restive

and

dispossessed spooked the “Tsar Liberator” Alexander II into a compromise arrangement that made Russia’s newly landed citizens nominally self-sufficient but still retained significant power for the landowners. In this way, then, as historian David Christian suggests, “it is reasonable to maintain that the liquor protests did play a significant role in the shaping of the emancipation settlement.”

32

Laissez Faire, Laissez Boire

In 1861, Alexander II liberated the peasants from serfdom and by ending the tax farm in 1863 liberated them from their slavery to vodka too… right? Unfortunately, no. Just as Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation was an important symbolic break with America’s feudal past that did not translate

into immediate freedom from domination, the same could be said about Russia’s emancipation. For one, the land the newly liberated peasants received was rarely enough for their own survival, while the crushing weight of the redemption tax—meant to compensate the landowner for the sudden loss of his workforce—effectively kept the village dependent on the landowner. Likewise, the dumping of the tax farm for a free market system that collected only an excise of four rubles per bucket (or

vedro

—3.25 gallons) of 100-proof spirits only masked the continued subservience of Russian society to the state through the bottle.

33

The new system effectively strengthened Russia’s state capacity by expanding its bureaucracy to take over functions that had been outsourced to the tax farmers. Regulating the liquor trade and collecting vodka revenues required recruiting over two thousand honest and competent civil servants—no small task. To reduce the incentives for bribery, the new administrators had to have no ties to the former system and had to be paid well—to the tune of over three million rubles per year in combined salaries. The system aspired to meritocracy: well-performing regulators received bonuses while incompetence, nepotism, and corruption would be punished. Still, elements of the old system endured. For one, the tavern remained untouched as the central exchange point between the village and the state, and the tyranny of the unscrupulous

tselovalnik

, or tavern keeper, continued unabated. Also, many of the tax farmers who had long profited handsomely from the drink trade simply moved into the lucrative practice of distilling—since it was effectively no longer monopolized by the nobility—and colluded to hide much of their actual production to avoid paying the excise tax.

34

The greatest continuity, however, was the state’s reliance on vodka revenues. As

figure 9.1

demonstrates, from the introduction of the excise system in 1863, government revenues crept upward steadily before being replaced by a state vodka monopoly in 1894 (at which time they increased even more dramatically).

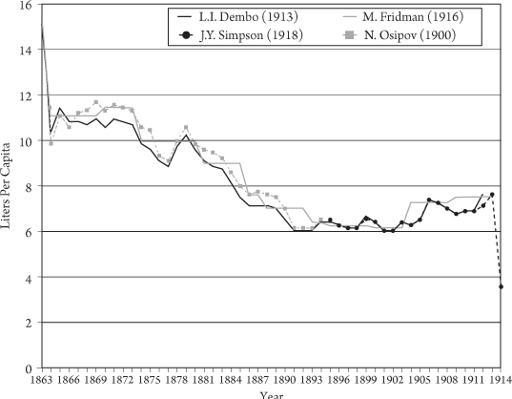

Did the demise of the tax farm lead to cheaper vodka prices, and an “orgy of drunkenness,” as the defenders of the old system warned? At first, perhaps: with their tax farms expiring and with warehouses of vodka to dispose of before the introduction of new taxes and market competition, the years around 1863 saw a spike in alcohol consumption. Overall, though, the years of imperial Russia’s excise tax experiment generally saw a gradual decrease in alcohol consumption (see

figure 9.2

).

The slight decline of consumption and simultaneous increase in alcohol revenues in the late nineteenth century hints at the autocratic state’s steady retreat from laissez faire principles to reestablish a greater presence in the vodka market. Liquor licenses in 1865, for instance, cost all of 10 rubles—twenty years later, they had risen to 1,100 rubles, leading to fewer outlets. In another effort to squeeze out every kopeck, the government increased the excise tax in 1864, 1869, 1873, 1881, 1885, 1887, and 1892, leading to gradual decreases in consumption.

35

Figure 9.2

E

STIMATES OF

R

USSIAN

P

ER

C

APITA

C

ONSUMPTION OF

40-P

ROOF

V

ODKA

, 1863–1914 Sources: L. I. Dembo,

Ocherk deyatel’nosti komissii po voprosu ob alkogolizmeza 15 let: 1898–1913

(St. Petersburg, Tip. P. P. Soikina, 1913), 163; Mikhail Fridman,

Vinnaya monopoliya, tom 2: Vinnaya monopoliya v Rossii

. (Petrograd: Pravda, 1916), 66, 265, 444; Nikolai Osipov,

Kazennaya prodazha vina

(St. Petersburg: E. Evdokimov, 1900), 77; J. Y. Simpson,

Some Notes on the State Sale Monopoly and Subsequent Prohibition of Vodka in Russia

(London: P. S. King & Son, 1918), 32.

Many countries of Europe and North America achieved similar decreases in alcohol consumption but by different means: political reform coupled with grass-roots temperance activism.

36

Yet while the vodka market was heavily regulated, it was at least nominally free—unlike the tsar’s subjects. With civic activism still outlawed, ordinary Russians could scarcely hope to stand up to the imperial alco-state. For all of the modernizing reforms of Alexander II, the state still largely relied on alcohol revenues (

figure 9.1

) and would not tolerate any threat to the state’s finances, no matter how well intentioned. If temperance were to succeed, the Russian state would fail—it was as simple as that.

“In 1865 the people fancied that because they were no longer serfs they could not be treated so unceremoniously as of yore,” wrote British journalist Eustace Clare Grenville Murray about Russia’s temperance aspirations, “but they found out their mistake. They were simply dealt with as insurgents, and though not

beaten, were fined, bullied, and preached at till there was no spirit of resistance left in them.” Written in 1878, Murray’s

Russians of To-Day

explained:

A person may also be severely punished for not getting drunk, as a certain Polish [!] schoolmaster whom we met one day disconsolately wielding a besom on the quays in company of a dozen kopeckless rogues who are being made examples of because they have no friends. The crime of our schoolmaster was that he lifted up his voice in his school and in tea-shops against “King Vodki,” and tried to inveigle some university students into taking a temperance pledge. He was privately warned that he had better hold his peace, but he went on, and the result was that one evening as he was walking home somebody bumped against him; he protested; two policemen forthwith started up, hauled him off, charged him with being drunk and disorderly, and the next day he was sentenced to sweep the streets for three days—a sentence, which fortunately does not involve the social annihilation which it would in other countries.

The fact is that in Russia you must not advocate temperance principles; the vested interests in the drink trade are too many and strong. Nobody forces you to drink yourself; the Raskolniks, or dissenters, who are the most respectable class of the Russian community and number 10,000,000 souls, are in general abstainers, but they, like others, must not overtly try to make proselytes. There are many most enlightened men who hate and deplore the national vice, who try to check it among their own servants, who would support any rational measure of legislation by which it could be diminished; but if one of them bestirred himself too actively in the matter he would find all his affairs in some mysterious fashion grow out of joint. Authors and journalists are still less in a position to cope with the evil, for the press censors systematically refuse to pass writings in which the prevalency of drunkenness is taken for granted.

37

Even after winning their emancipation, the peasantry of late-imperial Russia knew little more of freedom than that of their forefathers. Instruments of mass servility can take many forms—so even when it came time to put away the whips and chains, vodka remained. Indeed, the bottle proved to be an even more durable and effective means of maintaining dominance and control. Not only did it mollify the people; it made a tremendous profit in the process.

“It must be remembered that the policy of the Russian Government has always been to keep the State wealthy at the expense of the population. Ever since Ivan the Terrible the Tzars have been fabulously rich princes of a very poor

country.” Writing in 1905, Italian diplomat and historian Luigi Villari explained that “it enables the Government to undertake great schemes of territorial expansion while keeping the people in a state of economic subjugation and rendering them incapable of rising against their rulers. Of course the final object is to increase the wealth and the importance of the whole Empire, but everything is done from a narrow bureaucratic point of view, so that the end is apt to be forgotten in the elaboration of the means.”

38

The macabre beauty of building such a system on a foundation of vodka was that the peasant did not see vodka as the source of his bondage but, rather, as an escape to freedom.

39

The bottom of the bottle promised sweet annihilation from life’s boundless disappointments and hardships. For the drinker, there was no escape: the only escape from slavery was a different slavery—one disguised as freedom. For the state, it was an almost perfect system—so long as the state need not concern itself with the well-being of its society. Of course, only autocracies can completely disregard the interests of their peoples, which is why it is necessary to understand vodka politics as an intractable and enduring element of Russia’s autocratic system, from its very beginning to the present.