Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison

Read Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison Online

Authors: David P. Chandler

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Political, #Political Science, #Human Rights

BOOK: Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison

11.16Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Voices

from S

-

21

Terror

a11d

l

l

istory

in Pol

Pot

'

s

Secret

P

riso

11.

L)a,

id

c

:

ha ndlcr

Voices from S-21

A

B O O K

The Philip E. Lilienthal imprint honors special books

in commemoration of a man whose work

at the University of California Press from

1954

to

1979

was marked by dedication to young authors and to high standards in the field of Asian Studies.

Friends, family, authors, and foundations have together endowed the Lilienthal Fund, which enables the Press to publish under this imprint selected books

in a way that reflects the taste and judgment of a great and beloved author.

David Chandler

Voices from S-21

Terror and History in Pol Pot’s Secret Prison

University of California Press Berkeley

Los Angeles London

University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd. London, England

© 1999 by the Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chandler, David P.–.

Voices from S-21 : terror and history in Pol Pot’s secret prison / David Chandler.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 0-520-22005-6 (alk. paper).

1. Torture—Cambodia. 2. Political prisoners— Cambodia. 3. Political persecution—

Cambodia. 4. Genocide—Cambodia.

5. Cambodia—Politics and government—1975–79. I. Title.

II. Title: Voices from S-Twenty-one. HV8599.C16C48 1999

303.6

'

09596—dc21 99-13924

CIP

Manufactured in the United States of America 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 99

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997)

(Permanence of Paper).

Preface vii

- Discovering S-21 1

- S-21: A Total Institution 14

- Choosing the Enemies 41

- Framing the Questions 77

- Forcing the Answers 110

- Explaining S-21 143

Appendix. Siet Chhe’s Denial of Incest 157

Notes 161

Bibliography 207

Index 233

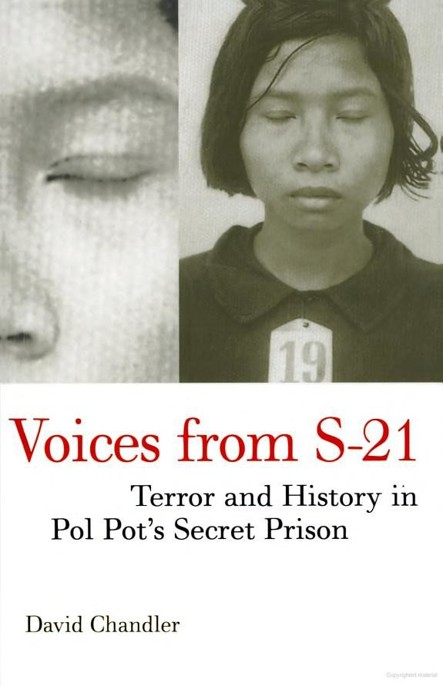

Photographs follow page 76

In April 1975 armed Cambodian radicals, known to the outside world as the Khmer Rouge, were victorious in a fi -long civil war. Almost at once, and without explaining their rationale, the Khmer Rouge forcibly emptied Cambodia’s towns and cities, abolished money, schools, private property, law courts, and markets, forbade religious practices, and set almost everybody to work in the countryside growing food. We now know that these decisions were made by the hidden, all-powerful Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) as part of its plan to preside over a radical Marxist-Leninist revolution. The Khmer Rouge regime of Democratic Kampuchea (DK), led by a former schoolteacher using the pseudonym Pol Pot, was swept from power by a Vietnamese invasion in January 1979. By then, perhaps as many as 1.5 million Cambodians were dead from malnutrition, overwork, and misdiag-nosed and mistreated diseases. At least another 200,000 people, and probably thousands more, had been executed without trial as “class enemies.” Overall, roughly one in five Cambodians died as a result of the regime. Because so many of the victims were ethnic Cambodians, or Khmer, the French author Jean Lacouture coined the term

auto-genocide

to describe the process.In August 1981, two years after the collapse of the Pol Pot regime, I traveled to Phnom Penh with four academic colleagues. It was the first

vii

time in ten years I had been in the city. During our three-day sojourn we were struck by the way that the city and its people seemed to be recovering from their catastrophic experiences in the 1970s, when foreign invasions, a ruinous civil war, and the Khmer Rouge regime had successively swept through Cambodia with typhoon force. The people’s courage and resilience in 1981, however, could not diminish the horrors of the Khmer Rouge era.

On our second day in Phnom Penh, we were taken to see the Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocidal Crimes, located in a southern section of the city. The museum had been set up by the pro-Vietnamese regime that had replaced the Khmer Rouge. It had been open to the public for about a year and was a prominent feature of government-organized tours for foreign visitors. In prerevolutionary times, we learned, a high school had occupied the site. Under the Khmer Rouge the abandoned school became the headquarters of the regime’s internal security police or

santebal.

This secret facility, known as S-21, was an interrogation center where over fourteen thousand “enemies” were questioned, tortured, and made to confess to counterrevolutionary crimes. All but a handful were put to death. The existence of S-21 was known in the DK era only to the people inside it and to the country’s leaders, who were themselves concealed from view.Two Vietnamese photographers had stumbled across the compound in January 1979, in the aftermath of the invasion. They discovered the bodies of “about fifty” recently murdered prisoners, instruments used for torture, and a huge, hastily abandoned archive. It was clear to them that under the Khmer Rouge S-21 had been an important and horrific institution. Within days the site was cleaned up and shown to sympathetic foreign visitors. Over the next few months, under Vietnamese guidance, it was transformed into a museum.

On our guided tour we were first taken to small classrooms on the ground floor. We saw metal beds, fetters, and photographs of murdered prisoners taken by the Vietnamese when they had entered the compound in 1979. In other ground fl rooms instruments of torture were displayed, alongside paintings by a survivor that depicted prisoners being interrogated, tortured, and killed. Hundreds of enlarged mug shots of prisoners were also posted on the walls.

On the second floor we saw the tiny cells assigned to prisoners being questioned and larger rooms where groups of less important captives were held. In a suite of smaller rooms we were shown what remained of S-21’s archive. Stacks of documents, some of them several feet high,

were piled into glass-fronted cabinets, on tables, and against the walls. The vast majority, it seemed, consisted of typed or handwritten confessions. There were over four thousand. Some covered only a page or two. A few, drawn from high-ranking prisoners, were several hundred pages long. Other documents in the archive included entry and execution records, interrogators’ notes, copies of speeches by DK officials, Khmer Rouge periodicals, cadre study notebooks, and biographical data about workers at the prison. We spent a few minutes riffling through the papers, taking desultory notes on the prisoners’ “treasonous activities” before emerging, numbed, into the darkening afternoon. Over the next few years, the visit lingered in my mind as other writers, including Elizabeth Becker, Ben Kiernan, and Steve Heder, drew on materials from the archive for their research. In the early 1980s, the human rights activist David Hawk assembled hundreds of documents from S-21 to use as evidence for an unsuccessful campaign to bring the leaders of DK to justice. Throughout the decade, copies of confessions circulated among scholars and journalists interested in the Khmer Rouge. Thanks to the generosity of these people and the cooperation of the museum staff, I used many of these documents for my own research before returning to Cambodia in 1990, when I spent several hours

working in the archive, assembling material to be copied.

In 1992 and 1993 the S-21 archive was microfilmed under the aus-pices of Cornell University and the Cambodian Ministry of Culture, which had jurisdiction over the museum. Judy Ledgerwood, John Marston, and Lya Badgley supervised the microfi at different times. During this period I visited Cambodia four times and kept track of the microfilming project. When the microfilming was complete, the prospect of examining the S-21 archive in depth and at leisure struck me as tempting, and I began to map out an agenda.

I hoped initially to use the archive as the basis for a narrative history of opposition to DK. I soon discovered, however, that the truth or falsity of the confessions, along with the innocence or guilt of the people who produced them, could rarely be corroborated. For a narrative history of DK, I realized, I would have to cast a wider net, with no assurance that corroborating documentation for the confessions would ever come to light. On the other hand, the challenge of studying S-21 and its archive on their own terms remained attractive, particularly as a means of entering the collective mentality of the Khmer Rouge and also as a way of coming to grips with a frightening, heavily documented institution. Changing direction in this way soon led me to concentrate on

those texts that would help me answer such questions as: How did the prison work? Who were the “enemies” being held? How were interrogations structured? When was torture applied? Was S-21 primarily a “Communist” facility or a “Cambodian” one? Were there foreign mod-els for it? And so on. Between 1993 and 1998 I examined over a thousand confession texts, scanned hundreds more, and read all the administrative materials from the prison that had come to light. These included hundreds of documents that were discovered in 1996 and 1997, after the Cornell project was complete. Over the years I supplemented my readings in the archive with research in secondary literature, looking for comparative insights.

This book is the result. Over the years that it took me to write it, I received generous financial support for my research and incurred a mul-titude of intellectual debts that I am happy to acknowledge.

The greatest of these debts, extending over the past thirty-two years, is to my wife, Susan. During our sojourns in Melbourne, Paris, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere, she has shared the ups and downs of my teaching career and the joys and glooms of my research. She has read successive drafts of everything I’ve written. Her comments have improved everything she has read. She has accomplished all this with baffling good humor in the midst of her own busy professional life, in the course of raising our three children, and on top of many other interests. This book, like my earlier ones, would never have taken shape without her close reading, her support, and her astute suggestions.

Work on the book was formally set in motion when the vice chan-cellor of Monash University, Professor Mal Logan, underwrote the pur-chase of a set of S-21 microfilms for me to work with. John Badgley, the curator of the Southeast Asia collection at Cornell University, saw to it that all 210 reels were waiting for me in 1994 when I took up a fellowship at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C. Over the next eight months I familiarized myself with the archive, copied hundreds of confessions, and gave several seminars that helped me to refi my research focus and my conclusions. Back in Australia, the Australian Research Council provided me with a generous grant that defrayed the cost of research assistance and allowed me to copy hundreds of confessions onto paper. In 1995 a fellowship from the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation paid for further research assistance and a trip to Cambodia. The fellowship also allowed me to reduce my Monash teaching load for a semester. In March 1996, when I was ready to start writing, a resident fellowship at the Rockefeller Foundation’s study center at

Bellagio gave Susan and me an unimpeded month to consider how my research might be turned into a book.

At every stage of my work I have been favored with excellent libraries, assiduous administrative support, and superb research assistance. Library staff at Monash University and the University of Wisconsin were helpful in tracking down secondary materials. I am particularly grateful for the administrative support provided as the book was being written, fi at Monash by Val Campbell and Wendy Perkins, and later at the University of Wisconsin by Danny Streubing and at the University of Oregon by Martina Armstrong.

My talented research assistants at the Wilson Center, Thong-Chi Ton Nu and Tim O’Connell, refined the computerized index to the archive and hunted down invaluable secondary materials. For the next three years my research assistant in Australia was Sok Pirun, a survivor of the DK era who had been trained as a historian in Phnom Penh in the 1960s. Pirun gave unstintingly of his time, arranged some fascinating interviews for me, and translated dozens of key documents from the archive. As we worked together, he provided a running commentary on the project and thereby gave me an invaluable entrée into the murky thought-world of the Khmer Rouge. Another survivor of the DK regime, Mouth Sophea, took an interest in my work when I was teaching in Madison and helped me over several hurdles of interpretation. Over the years I have been buoyed up by friends and colleagues who have read all or part of the manuscript. These include Sara Colm, May Ebihara, Craig Etcheson, Kate Frieson, Alexander Hinton, Charles F. Keyes, Judy Ledgerwood, Alfred W. McCoy, and Keith W. Taylor. Steve Heder in particular has been unstinting in his help, sending me hundreds of pages of unpublished translations, several unpublished essays, numerous interview transcripts, and invaluable comments on the full text and on specific points. Several of Richard Arant’s graceful translations from the S-21 archive have found their way into the book, and I am grateful for his interest in the project. Henri Locard shared his findings about “the Khmer Rouge gulag” with me in 1995–1997, and my more recent discussions with Alexander Hinton about the collective psychology of the Khmer Rouge have helped me to reformulate some of

my ideas.

In 1994 I came to know Douglas Niven and Chris Riley, two intrepid photojournalists who formed the Photo Archive Group in Phnom Penh to clean, index, and reprint over six thousand photographs—the vast majority of them mug shots—from negatives that they discovered in woe—

ful condition at S-21. Along with their friend Peter Maguire, Doug and Chris provided me with transcripts of interviews they conducted in 1995 and 1996, and Doug arranged several interviews with former workers at S-21 that we conducted together in 1997 and 1998. Additional interview transcripts were kindly provided at various times by Richard Arant, David Ashley, Chhang Youk, Sara Colm, David Hawk, Steve Heder, Alexander Hinton, Ben Kiernan, Nate Thayer, and Lionel Vairon.

Soon after I began writing, I learned that the Cambodia Genocide project administered by Yale University had gained access to a range of new materials dating from the Lon Nol period (1970–1975) and the DK era. Thanks to Dr. Timothy Castle in the Office of the DPMO-MIA in the U.S. Department of Defense, I was given a contract to examine these materials to see whether they contained information useful to the MIA program. In 1997 I visited Cambodia three times to review the materials, now housed in the Documentation Center–Cambodia (DC– Cam) under the able supervision of Chhang Youk, whose enthusiastic help in 1997 and 1998 was crucial to DPMO-MIA and to my S-21 project. During these visits, Lach Vorleak Kaliyan, the archivist at the Tuol Sleng Museum, located and copied several hundred pages of materials that had been found at S-21 after the Cornell University microfilming project had been completed.

Many other people have been helpful to me along the way, clearing up specific points, making comparative suggestions, and sharing their ideas about the Khmer Rouge.

Other books

Fox Evil by Walters, Minette

Bound by Jenika Snow, Sam Crescent

Area 51: The Grail-5 by Robert Doherty

Martyr (The Martyr Trilogy) by Beckwith, N.P.

All Dressed Up and No Place to Haunt by Rose Pressey

Three Minutes to Midnight by A. J Tata

True Colors by Jill Santopolo

McNally's Dare by Lawrence Sanders, Vincent Lardo

It's a Don's Life by Beard, Mary