Volpone and Other Plays (27 page)

Read Volpone and Other Plays Online

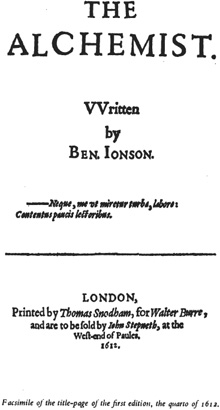

Authors: Ben Jonson

LOCATION AND TIME-SCHEME

The Alchemist

is set inside Lovewit's house, and outside his front door. The fluidity of the Elizabethan Theatre or of a modern composite stage-setting is necessary in performance, and the acting-area has to indicate two or three rooms inside the house, the street, and possibly the garden. The pace of the action is fast. Act II follows briskly upon Act I, and perhaps Sir Epicure Mammon and Pertinax Surly should already be coming into the audience's view in the street when Dol, inside the house, describes Sir Epicure's approach in the last lines of Act I, so that the action is really continuous. Act IV seems to require several locations â the principal room in Lovewit's house, two smaller rooms, and the garden, but Jonson did not specify locations, and an ingenious director, following the example of Sir Tyrone Guthrie in 1962, could set the scenes in the main area of traffic, and on the staircase, the balcony, and so on. The

décor

for

The Alchemist

, as for any modern farce, requires many doors and exit-points, including the privy in which Dapper is incarcerated. In the Herford-Simpson edition the time-scheme has been worked out from internal evidence as follows: 9 a.m.: arrival of Dapper; 10 a.m.: Mammon seen approaching; 11 a.m.: Ananias threatened if he does not return quickly with more money; noon: Ananias returns on the stroke of the hour; 1 p.m.: Dapper comes back as requested; 2 p.m.: Surly arrives in disguise; 3 p.m.: Lovewit returns home unexpectedly.

EDITIONS AND CRITICAL COMMENTARY

The Alchemist

is reprinted in many editions of Jonson and in anthologies, including

Elizabethan and Stuart Plays

, edited by C. R.

Baskervill, V. B. Heltzel, and A. H. Nethercot (1934). It has been edited by Felix E. Schelling (1903), by C. S. Alden (1904), and by G. E. Bentley (1947). F. H. Mares' edition for the Revels Plays (1967) appeared after the present volume. The editor for the Yale Ben Jonson is R. B. Young. J. J. Enck and E. B. Partridge both devote chapters to the play. Brian Gibbons in

Jacobean City Comedy

relates

The Alchemist

to other comedies satirizing life and to the coney-catching pamphlets. J. A. Barish's anthology of criticism reprints a section of Paul Goodman's

The Structure of Literature

(1954). which is an Aristotelian analysis of its comic plot. It was Coleridge who said âUpon my word, I think the

Oedipus Tyrannus, The Alchemist

, and

Tom Jones

the three most perfect plots ever planned.' (

Table Talk

: 5 July 1834.)

The Alchemist

is not primarily about alchemy, nor is Subtle a genuine alchemist. Throughout the comedy Jonson exploits alchemy and alchemical language as supreme instances of roguery and the bewitching verbal arts of the confidence-trickster. Although dramatic logic does not demand it, Jonson's use of alchemical terms, always theatrically telling, is usually accurate also. That Jonson made himself familiar with alchemical scholarship may be a further illustration of that massive erudition and pedantic thoroughness mentioned in the first pages of the introduction. Professor Edgar Hill Duncan has assured us that Jonson's knowledge of alchemy âwas greater than that of any other major English literary figure, with the possible exceptions of Chaucer and Donne'. The preoccupation with accuracy may be pedantry on Jonson's part, but it is surely significant that the various characters within the comedy who use alchemical terms use them more or less correctly â the credulous Sir Epicure, who is willingly dazzled by the lights of perverted science; the quick-talking Subtle, who is not a âcunning-man', but a con-man; and the sceptical Surly, who pours sardonic comments over Subtle's ill-founded but convincingly expressed pretensions. The main point of Jonson's satire, in this play as in

Volpone

, is that human greed and gullibility put men in the power of unscrupulous manipulators, but the accuracy of alchemical reference possibly indicates incidental Jonsonian satire on alchemy itself. Through the speeches of Sir Epicure, Jonson was able to make fun of the claims of the alchemists without having to resort to fantastic inventions of his own; their own claims, reproduced from alchemical treatises, seemed exaggerated enough. And in presenting his audience with Subtle, a bogus alchemist who sounds authentic, Jonson may have been hinting that all authentic-sounding alchemists were bogus also. It was the practice of alchemists to conceal their discoveries in symbolic language and in elaborate pictorial allegories and diagrams which remained mysterious and impenetrable to the un-initiated layman. This complex symbolism has subsequently

fascinated historians of ideas and others â for an account by a great modern European mind of the archetypal patterns in the alchemists' world-picture, see C. G. Jung's

Psychology and Alchemy

(British edition, 1953). The studiously cultivated mystery and obscurantism of the Renaissance alchemists probably amused and enraged the exact Jonson, who made of it comic poetry in

The Alchemist

.

Alchemy has a long history which itself forms the pre-history of chemistry. For some fifteen hundred years the alchemists, many of them sincere and dedicated men of science, pursued the hopeless task of transforming such base metals as lead or copper into silver or gold. The first European alchemical treatises date from the third and fourth centuries A.D. Alchemy existed earlier in China and in India, but the main Western tradition originated in Alexandria around A.D. 100. Medieval and Renaissance alchemists believed, as Sir Epicure does in Jonson's play, that men of former times had possessed the secret of transmuting base metals into gold; their own task was to recover that secret either by experiment or by poring over the mystical writings of their predecessors. The experimental and the scholarly approaches became, increasingly, separate activities, but until the middle of the seventeenth century it was in the laboratories of the alchemists that the apparatus and the experimental techniques of chemistry were developed.

Behind early alchemical thinking lay Greek assumptions about the relation between form and matter, derived from Aristotle, and about spirit. Aristotle believed that there was ultimately only one matter and that it could take any number of forms. F. Sherwood Taylor, the historian of alchemy, thus describes the task of the earliest alchemists: â⦠their endeavour to change, let us say, copper into gold, was planned as the removal of the form of copper (or, more picturesquely, as the death of copper and its corruption), to be followed by the introduction of a new form, that of gold (which process was pictured as a resurrection)'. The notion of spirit or breath is a difficult one; it indicates the subtle, almost immaterial influence which had to be present to make possible, say, the germination of a plant, or the transformation of matter from one form to another. The sentence quoted from

Taylor's book suggests how readily alchemical thinking lent itself to metaphorical expression. In Medieval and Renaissance times the language and iconography of alchemy became increasingly complex, drawing upon many sources. The early metaphor of the reduction of the metal as the slaying of the dragon was elaborated. Alchemists talked of the marriage of Sol and Luna, gold and silver, which, if it could be effected, would produce the Philosopher's Stone. The symbolic language frequently drew upon religion. Taylor writes: âThe death of our Lord Jesus Christ and His resurrection in a glorified body was to the alchemists to be compared to the death of the metals and their rebirth as the glorious Stone.' These three isolated examples are sufficient to show the range of mythological, analogical, and religious reference in alchemical symbolism.

Alchemy, which had disappeared along with Greek philosophy and science after the fall of Rome, was rediscovered in the Western world in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when scholars busied themselves translating into Latin the scientific and philosophic works of Islam, including Arabic treatises on alchemy. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries such great minds as Albertus Magnus, Roger Bacon, and St Thomas Aquinas, taking all human knowledge as their province, pondered very seriously the alchemists' explorations of the nature of matter. The attention they gave in their encyclopedic works to the alchemists' claims contributed to a revival of alchemical activities both through experimental work (notably by Geber or Jabir, a Spanish alchemist) and through the writing of mystical and, indeed, occult treatises on alchemy. In the fourteenth century there appeared more systematic and clearly written alchemical works, usually attributed to Arnold de Vallanova and to Ramón Lull, though on uncertain grounds. In England alchemists, both genuine and bogus, flourished; Chaucer's

Canon's Yeoman's Tale

is a satire on charlatans. A statute of 1403 forbade the multiplying of metals; and there are cases recorded throughout the fifteenth century of people obtaining royal licences to practise alchemy. English alchemists of the fifteenth century included Sir George Ripley who studied in Italy (and who is mentioned in this comedy), Thomas Norton, and Thomas Daulton.

Readers who wish to find out more about the alchemical background to

The Alchemist

will find a brief, old-fashioned article on Alchemy in

Shakespeare's England

(1917). A helpful book-length survey for the general reader, of which I have made use in this short summary, is F. Sherwood Taylor's

The Alchemists: Founders of Modem Chemistry

(reprinted 1958). More detailed is John Read's

Prelude to Chemistry: An Outline of Alchemy, Its Literature, and Relationships

(1936). Like Jung's

Psychology and Alchemy

both these books contain many illustrations from alchemical treatises, many of Read's plates being in colour. Edgar Hill Duncan's closely written article âJonson's

Alchemist

and the Literature of Alchemy' in

Publications of the Modern Language Association of America

, LXI (1946) shows how some speeches in the play become more significant in the light of detailed alchemical knowledge. I have drawn freely on his work in annotating certain passages in

The Alchemist

.

No edition for the general reader or playgoer can hope to cover the alchemical background thoroughly, and I have not tried to explain all the terms either in the glosses or in the longer explanatory notes. Jonson's alchemical terms fall into three main classes: (

a

) materials and substances, (

b

) alchemical equipment and apparatus, (c) alchemical processes. The following selective glossary may assist the reader and playgoer.

(a)

Materials, substances etc

.

adrop

: the matter out of which mercury is extracted for the Philosopher's Stone; the Stone itself.

aqua fortis

: impure vitriol.

aqua regis

: a mixture of acids which can dissolve gold.

aqua vitae

: alcohol.

argaile

: unrefined tartar.

aurum potabile

: liquid, drinkable gold.

azoch

: mercury.

azot

: nitrogen.

calce

: powdered substance produced by combustion or âcalcination'.

chibrit

: mercury.

chrysosperm

: elixir.

cinoper

: sulphide of mercury.

kibrit

: sulphur.

lac virginis

: mercurial water.

lato

: a mixed metal which looks like brass.

maistrie

: the magisterium or Philosopher's Stone.

realga

: a mixture of arsenic and sulphur.

sericon

: black tincture.

zernich

: auripigment or gold paint

(b)

Alchemical equipment and apparatus

alembic

: the vessel at the top of the distilling apparatus which holds the distilled material.

aludel

: subliming pot.

athanor

: a furnace.

balneum

: bath; or process of heating a vessel.

bolt's head

: a long-necked vessel.

cross-let

: crucible.

cucurbite

: a distilling vessel.

gripes egg

: a vessel shaped like a vulture's egg.

lembek

: a still.

pelican

: an alembic.

(c)

Processes

ceration

: softening hard substances.

chrysopÅia

: the making of gold.

chymia

: alchemy.

cibation

: seventh stage in alchemy.

citronize

: to become yellow.

cohabation

: redistillation.

digestion

: preparation of substances by gentle heat.

dulcify

: to purify.

inbibition

: a bathing process associated with the tenth stage.

inceration

: softening to the consistency of wax.

macerate

: to steep.

potate

: liquified.

projection

: the twelfth and last stage in alchemy.

putrefaction

: the fifth stage in alchemy whereby impurities were removed by the use of moist heat.

solution

: the second stage in alchemy.

spagyrica

: the spagiric art; Paracelsian chemistry.

sublimation

: conversion into vapour through the agency of heat, and reconversion into solid through the agency of cold.