Waggit Again (2 page)

Authors: Peter Howe

W

aggit ran and ran until he could run no more and had to lie down in some bushes, panting as if he would never stop. He was pretty sure that he was far enough away now, so even if the farmer did come looking for him the man would be unlikely to find him. But although he was feeling safe, he was also feeling lost. He had no idea where he was or which way he should go. Whichever direction he took, he would have to be careful. Although dogs alone on country roads might be a more familiar sight than in the city, those with

two feet of chain attached to their collars would attract unwanted attention.

He got up from the bushes and stretched. He had found that stretching was a good thing to do when you had to make a decision; it seemed to make thinking easier. He sniffed the air as if trying to pick up some scent of the city. He knew this was silly and that his home was many miles from here, but even so he felt a tingling in his nostrils when he faced in a certain direction, not a smell exactly but a sort of feeling. His whiskers also twitched like a water diviner's rod. He turned around in a full circle several times, but the sensation only happened when he was facing one particular way. Since he had nothing else to guide him he decided to follow this instinct and headed down the road in that direction.

In the distance he heard the sound of a truck snorting as it applied its brakes and rounded a bend. Waggit quickly jumped into the ditch on the side of the road and lay as flat as possible until the vehicle, a large milk tanker, passed him by. The sky was quite light now, and it would be safer if he could find a route that wasn't a highway. More and more cars were about, and soon he was spending as much

time hiding in the ditch as walking.

He had gone several miles and was beginning to feel tired and hungry when he came upon a lane that went away from the highway and into the fields. It was deeply rutted where tractors or trucks had used it, and it looked interesting to the dog. On either side stone walls and thick, prickly bushes hid him from sight; it seemed a better alternative than the road. He was still too scared to relax though, and he moved quickly along, glancing over his shoulder every few feet to make sure that he wasn't being followed. He had gone only a short distance when his heart sank. The path ended at a metal gate that led into an empty field from which there appeared to be no exit.

But then something at the far end of the field caught his attention. It was a tall, grassy embankment, on top of which he could see poles with wires strung between them. Something about the embankment aroused his curiosity and he squeezed his body under the bottom of the closed gate and headed toward it. He quickly ran across the field and scampered up the side of the ridge.

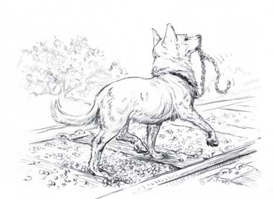

When he came to the top he was on a flat surface covered in small rocks, over which ran two strips of

metal that were mounted at intervals on crosspieces of wood and seemed to go on forever. Waggit had no idea what all this was forâhe had never seen a railroadâbut he could see it was free of cars, trucks, and people. His nose told him it was heading in the right direction. Taking it, however, was easier said than done. The rocks hurt his feet, and the wooden planks were spaced too far apart for comfort. He tried walking beside the tracks, but the slope was too steep and it tired him. The best he could do was stay between the rails, and after a while he got into a rhythm alternating between rocks and planks that made it bearable.

Apart from the surface, the railroad tracks were perfect. They went through deep countryside, and not only did he see no people, he rarely saw houses, and when he did they were far in the distance. The sun had been up for some time and was warm without being hot. Birds were singing in the trees, and he smelled a hint of cherry blossoms. He felt so lighthearted that he even dropped the chain from his mouth and let it jingle musically on the ground. Although he was fearsomely hungry, at least he wasn't thirsty. The tracks had gone through a deep cutting in the rock, with sheer sides rising up many feet. From a crack in the walls a small

waterfall descended, and under this Waggit quenched his thirst and cooled his body.

His feeling of contentment was short-lived, however. No more than a mile from the cutting, the tracks ran through more open countryside. Suddenly he felt the earth beneath his paws begin to vibrate, gently at first, and then more noticeably. His ears picked up the sound of rumbling, not the kind that trucks made but much different. Then he heard the shriek of a whistle, and as he turned and looked behind him he saw a terrible sight. An awesome metal monster was bearing down upon him, its single headlight glaring like a huge, malevolent eye, angry black fumes coming out of its nostrils.

Waggit just had time to throw himself down the embankment before the beast was upon him. It roared past, an unstoppable force, dragging dozens of large metal boxes behind it. These were freight cars that clattered rhythmically over the joins in the rails, sounding like they were saying, “Gotta go, gotta go, gotta go.” The train appeared to be endless, and Waggit feared he would never be able to walk along the tracks again, but finally, after what seemed like hours, the last car passed. Silence once again descended on the landscape,

although the dog couldn't tell because the sound the locomotive had made was so loud that his ears were still ringing.

“Well, young man, who are you and where are you going?”

Waggit spun around to see a woman standing behind him, not young but not really old either. He hadn't heard her come up because of the noise reverberating in his head. She was dressed in an assortment of strange, mismatched clothes. She had a scarf tied under her chin with an old and ragged baseball cap on top of it. Across her shoulders she wore a cape, now faded to a pale blue but still trimmed in red. Beneath it was a thick woolen plaid shirt of the kind that people think lumberjacks wear. She had on a flowing skirt that came below her knees with black sweatpants under it, and on her feet were a rugged pair of work boots. The entire outfit should have looked ridiculous, but the way she carried herself gave it a stylish quality.

Waggit's first instinct was to back off and put up his hackles, but there was something about her that was strangely soothing, and he realized that he didn't fear her at all. He wasn't sure why; it might have been the sound of her voice, which was musical and calming,

but it was more than that. Just being near her made him feel peaceful. He cocked his head and looked at her. Then he realized she had asked him a question.

“My name is Waggit,” he replied, “and I'm trying to go home.”

“I'm very pleased to meet you, Waggit,” she said in her wonderful voice. “My name is Felicia. Now where exactly is your home?”

“It's where my friends live.”

“Hmm.” She considered this thoughtfully. “That doesn't give us much of a clue as to whether or not you're going in the right direction.”

“Well,” he said, “every time I turn this way my nose tingles, so I think it's right.”

“Yes,” Felicia agreed, “that's always a good sign.”

Then something struck Waggit with the force of the train. He understood what she was saying, and she understood him. Not only that, she spoke to him the way dogs talk to each other, without making a sound and without moving her lips. Her words just popped into his brain the way they did with other dogs. This had never happened before with a human being.

“How come you know what I'm saying? I mean, you're an Upright, and Uprights can't understand

dogs.” He cocked his head in confusion.

“I'm a what?”

“An Upright, you know. You're a people.”

“Well, I suppose I am. I just never heard that term before,” she said.

“So?” persisted Waggit. “How come?”

“Well, I may be an Upright, but I also have”âshe paused for an instantâ“shall we say, certain powers that most people don't have, or at least don't think they have.”

“That's amazing,” said Waggit, truly impressed. “Can you talk to all animals?”

“I don't know,” she replied. “I suppose I could if I tried, but I only bother with the ones I like. You dogs are my favorites, with horses second, and I also find pigs quite amusing. Cows are rather dull, and I don't like cats. They're way too full of themselves.”

“Do other Uprights who can't talk to their animals ask you to tell them what we're saying?” he inquired.

“Bless you, no,” she said with a twinkle of amusement in her eyes, “quite the opposite. They think I'm strange, to put it mildly. To them I'm just a little less threatening than a witch.”

Waggit didn't know what a witch was, but the

thought of this calm woman with her soothing voice being a threat to anyone seemed odd to him.

“Come,” she said, “you have a âlean and hungry look' as Mr. Shakespeare said, and I think I have some sausages that we can cook up. Let's go to my place.”

Waggit didn't know who Mr. Shakespeare was either, but whoever he was he apparently knew a thing or two about dogs and their digestive systems, because the word

sausage

caused Waggit's stomach to start growling louder than Hodge in a bad mood. He trotted along beside her until they came to a small tent set a little way back from the tracks. She had covered it with leaves and branches so that at first sight it was almost invisible. A narrow, clear stream ran close to the tent, and Waggit ran to it to drink and let the cold water wash over his paws and ease the soreness from walking on the rocks that lay beneath the rails.

When he went back to the campsite Felicia was putting some sticks and dead, dry leaves into a circle of blackened stones. She then disappeared inside the tent, and Waggit could hear her muttering to herself.

“Matches. Matches. Now come on, matches, where are you?”

After a couple of minutes he heard her cry, “Ah-ha!”

and she reemerged, her baseball cap slightly crooked, triumphantly holding a large box of matches in her hand. She busily lit the fire, talking to the matches all the while, encouraging them to do their work. Once she got a good blaze going she let it burn for a while until all that remained of the wood were hot, glowing embers. She placed an old, battered frying pan on the coals, and into this she threw some fat sausages. Soon the sound of sizzling and the delicious smell of meat cooking wafted through the air, causing Waggit to drool.

Felicia noticed this and said, “I know that it doesn't matter to you whether they're cooked or not, but since I live without the benefits of a refrigerator it's probably best that we heat them through. We don't want you getting sick.”

Although this was sensible, it was also a nuisance, as many sensible things are. By the time she put the food on a plate and placed the plate on the ground, Waggit thought he would faint from hunger. The actual eating of the sausages was the shortest part of the whole process, and when it was over, and the dog got that wonderful, restful sensation of a full stomach, he belched softly.

“Now that you've eaten,” she said as she cleaned out the frying pan with a handful of grass, “let's try to work out where your home is.”

She put the pan back into the tent and turned toward him only to find that he was fast asleep, exhausted from the excitement of the day's adventures and the effect of the food.

“Oh well, maybe later,” she said kindly.

W

aggit awoke to the sensation of being stroked. Felicia was gently smoothing the fur down his back and caressing him behind his ears. She made him feel safe and peaceful, more relaxed than before his owner had left him at the farm.

“Welcome back,” she said as he stretched and yawned.

He got up and shook himself, and in doing so realized that she had gently taken off the length of chain while he slept. This was a great relief, because even

though it didn't weigh much, it did get in the way and, worse, it was a reminder of his recent captivity. He wagged his tail in gratitude and then sat down again.

“Well,” she said, “I think we know where your home isâor at least where it was at one time.”

She reached over to his collar and shook the rather battered red tag that hung from it.

“That, my friend, is a rabies vaccination tag from a New York City vet. So we know you lived in New York at one time. Why you don't have any other identification tags I have no idea.”

Waggit remembered that in his fight with Hodge some of the stuff that jingled from his collar had been ripped off and fallen to the ground, never to be reattached.

“New York sounds familiar,” he said uncertainly.

“Was it a big city with lots of people and very tall buildings?”

He nodded.

“And yellow cabs?” she asked.

“I don't know what a cab is,” he admitted.

“You know, a car,” she said. “A big metal thing that goes along the road carrying peopleâer, Uprights, that isâinside.”

“Oh, a roller.” He finally understood. “There were a lot of rollers that color.”

“Assuming that a roller is a car, then we can also assume that the yellow ones were taxis. I think,” she said, “that your home is New York, and that you're a long way from it. How did you end up in this neck of the woods?”

“I was living with a woman. She was the one who rescued me from the Great Unknown.”

“The Great Unknown? I don't think I've ever heard of that.”

“It's where they take you when they catch you in the park,” explained Waggit. “Anyway, we lived together for many risings, and everything seemed just fine until one day she suddenly put me in a roller and brought me to a farm near here and left me there.”

“Why did she do that?” asked Felicia.

“I don't know.” The dog was really confused. “I thought she liked me; she seemed to. I liked her, and I trusted her, but she abandoned me, like the first Uprights I lived with did.” He suddenly was shaking with anger. “That's what you get for trusting Uprights. I should've learned my lesson; I promise you I'll never trust another one.”

“Whoa, slow down there. I'm an Upright and you trust me, don't you?” said Felicia.

Strangely enough, he did, although he wasn't sure why.

“Also,” the woman continued, “there are many reasons to leave a dog somewhere. It doesn't necessarily mean she abandoned you. Maybe she left you there because she had to go away and wanted them to look after you. Maybe she was coming back.”

“No,” said Waggit. “She never went away for that long. It was too many risings ago. No, she abandoned me.”

“Oh dear, you do feel sorry for yourself.”

“So would you if you'd been abandoned, for the second time, as it happens.”

“No I wouldn't,” she cheerfully contradicted him. “I would say to myself: Here's the opportunity to do something different; here's the possibility of an adventure.”

“That's easy for you to say,” replied Waggit, somewhat resentful of her breezy optimism. “You've probably never been abandoned.”

“Actually, I was, in a way.” He waited for her to explain what she meant by this, but she fell silent.

“Look,” she said after a few minutes, “why don't we do this? I haven't been to New York City in a long time, and it might be fun to see if it's changed. I've nothing special to do at the moment, so why don't I join you and we'll go there together? Sound like a plan?”

It did sound like a plan to Waggit, especially since he didn't have one of his own. Furthermore, she made him feel happy, even if he didn't particularly want to be. He wagged his tail in agreement.

“Good,” Felicia exclaimed, “that's settled. Let's shake on it.”

She extended her hand, and he put his paw in it. It was a deal. They were traveling companions.

“I think,” said Felicia, “that with all due respect to your nose, I shall buy a map at the first opportunity.”

They decided that they would start out in the morning, and as the day drew to a close the woman prepared yet another meal. This time she opened cans of beef chili and warmed them in the same pan in which she had cooked the sausages. She put two large dollops of the food on a plate for herself but let Waggit eat his directly from the pan, when it had cooled down. Of course, being chili, even when it had cooled down it was still hot, because that's the

way chili is. It surprised the dog, who had never tasted spicy food before, but when he got used to it he found it delicious, and furthermore, as he licked the last remnants from the pan he could still taste the morning's sausages.

While the woman washed out the utensils in the stream before it got totally dark, Waggit lay by the opening of the tent licking his paws. He looked at Felicia as she worked. He had never met a human like her before. It wasn't just that she understood what he said or the peace he felt in her companyâboth of these things were remarkable enoughâbut she also didn't seem to have any of the worries and concerns that other humans had. She wasn't always in a hurry, and from the eccentric way that she was dressed she clearly didn't care what other people thought of her. She was so calm and confident that he couldn't imagine her being frightened.

“Are you ever afraid of things?” he asked her when she returned.

“Not often,” she replied. “I've found that things are rarely as scary as you think they're going to be. That's the trouble with fear. It holds you back. It stops you

from doing things that might be fun or might be good for you. Take this journey we're about to go on. I'm sure we'll come across stuff that won't be what we expect, and some parts of it will be difficult, but if you let fear of what might happen stop you, then you might as well stay right here forever.”

Funnily enough Waggit had been thinking that living with Felicia in the tent by the stream was so nice that maybe they shouldn't take the long and possibly hazardous trip back to New York, but he didn't mention this to her.

“I'll give you an example,” Felicia continued. “When we get to New York we've got to find where your woman lives. Locating someone in a big city is difficult even if you have a name and address, neither of which is in our possession, and New York is as big as big cities get. But I know that once you start moving forward, things have a tendency to fall into place, and so I have no doubt that it'll work out.”

Waggit sat there, stunned.

“Butâ” he began.

“No,” said Felicia. “Not another word. We'll find her if it takes every power that I possess.”

“Butâ” Waggit tried again. “But I don't want to find her.”

“You don't?” asked Felicia, puzzled. “I thought you wanted to go home.”

“I do,” said Waggit. “I do want to go home. I want to go home to the park.”