Wake Up and Dream (20 page)

Authors: Ian R. MacLeod

Focus, Clarkie. Think. Stay in character.

April Lamotte had almost certainly left Dan up here whilst she was in the city getting her plans sorted, coming back up again once or twice to keep him semi-calm, and probably take away and mostly destroy whatever he was writing. Except that last time, when she’d ended up dead a few miles down the road in her Cadillac. When someone else had perhaps come to get him instead. So many things to remember. The jigsaw sliding loose and somehow trying to fit in ways that made no sense.

But think—think like the guy you really are. It’s just a matrimonial. Someone fucking someone else. Just a question of the wrong kind of stains, the right kind of evidence. So where else would you look?

He peered under the bed, felt between the base and mattress. Then, what the hell, tipped the whole thing over. Nothing but dustbunnies and a lost sock. He went back into the bathroom. He sat down on the toilet seat, looked sideways, behind and up. A small metal wastecan stood in the corner beside him. He’d seen them before in out-of-the-way places where the septic tanks couldn’t cope with too much paper waste. But you’re a matrimonial investigator, Clark, so where else would you look? Turning sideways again, using the toe of Daniel Lamotte’s brogue, he flipped the lid up.

First thing he saw was enough to make him glad he’d done so. If glad was the word. A syringe exactly like the one he’d found at the overlook, or near as damn, lay on top of a balled mess of pink papers. Its plunger was down. He stood up and reopened the cabinet on the wall, just to confirm there was no sign that April Lamotte was using any of the kind of medicines you’d administer with a needle. He’d heard some dopers were starting using such things, but if that was what Dan had been up to, the signs would surely have been more obvious.

He sat back down on the toilet, lifted the lid of the wastecan again and prodded around in the toilet paper with some reluctance; there are some jobs even an unlicensed matrimonial private eye turns his nose up. Didn’t look as if there was another syringe further down, but… but… Don’t want to get too clinical here, Clarkie baby, but there’s something pretty odd about some of the marks on those pink sheets.

He picked one out by its edge. It was marked alright, but not the way you’d expect. Scrawling bursts of letters and torn-through underlinings. Mostly in pencil, although some of the deeper clumps were written in splatters of blueblack ink. Some of the top stuff which he’d hesitated at first to touch was brown, but not in the way you’d expect. Jesus—the guy had actually written in

blood

.

As to what it said… The paper was flimsy in the first place, for all that it was expensive two-ply, and hardly designed for this purpose. And then there was Daniel Lamotte’s handwriting, which had been bad enough in those sheets he’d tried to decipher in room 4A, but sometimes here barely looked to be English at all. Still, some words stood out.

Wake

and

Up

and

Dream

, for instance. And, repeatedly,

Lars Bechmeir

. Much of it, though, remained incomprehensible. The stuff was like some kind of code you could only understand when you already knew what it was about. Still, a scrawl that was recognizably

Howard Hughes

figured a great deal. The

Met

and the

Metropolitan Hospital

occurred frequently as well, which made just as little sense as it had in those missing torn out pictures, considering it was the place where the guy had ended up only after his sanity had collapsed. The seemingly made-up word

Thrasis

was in there as well, which sounded familiar. And many of the references were savagely underlined, or Daniel Lamotte had returned to the same sheet to re-mark them until the paper gave out. All very strange. But not the strangest thing of all.

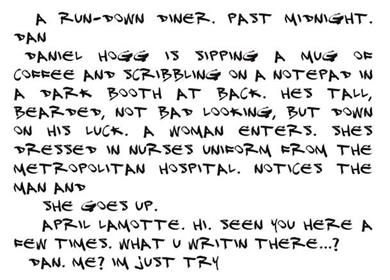

Here was the first scene of the latest version—the

pink

version, it suddenly occurred to him—which came in the standard color sequence for script revisions right after blue. Something resembling the words

Scene One Wake Up and Dream

was written across the top. Picking through the sheets, some of which were still strung by their perforations and some of which had been torn into smaller scraps, he was even able to make some sense of them. The reason being not a sudden improvement in Daniel Lamotte’s handwriting, but because he recognized the scene.

Then the sequence gave out in a confetti of starbursts, scrawls, exclamations, pentagrams, weird symbols, and splatters of shit and blood.

H

E TOOK A WRONG TURN

on his way back out of Bark Rise, and nearly got the Delahaye’s wheels stuck in the ruts of a loggers’ clearing.

Peaks clawed into view above the treeline as he re-found a road and drove on. He glimpsed narrow ravines and cols of snow, then the landscape opened out. From here, the mountains fell away and the land opened north into high desert. He’d managed to find some kind of pass.

The wind whipped hard and cold. He got out, took a breath, had a smoke. The thought came to him that he could have left Daniel Lamotte somewhere back around that lodge. Buried in the ground, hanging from a tree, or burnt in another bonfire. The thing of it was, he felt sure that he’d have found the guy if he was there. Which, as thoughts go, hardly helped. For it meant that he was following a trail that had been laid down.

The high desert glowered beneath thunderhead clouds. Lightning flickered. Shadow chased shadow. Hard-driven sand abraded his face. He got back in the Delahaye, consulted April Lamotte’s foldout map.

He stopped again at the gas station—with the wall-eyed man and dog—back on the Pasadena road, and used the payphone inside the dark little store. He again tried the number for Nero Securities. Once more, there was no answer. Then he got the operator to put him through to the phone booth on Blixden Avenue. It rang for about half a minute. Then came a clattering pick-up.

“Yeah?”

“That you, Roger?”

“Who else, my friend, do you expect it to be but I?” He was doing a cruddy English-baddie accent.

“Anything happening there?”

“Like what?”

“Haven’t seen anyone around have you? Perhaps some tallish, thin guy—probably driving a black Mercury sedan with some kind of badge on the side, wearing aviator glasses and dressed in uniform. Police, or the utilities—”

“Uti… .?”

“I mean gas, power, water. Possibly a security firm. You understand?”

“Yeah. But the only guy in uniform we sees around here apart from those cops you got sniffing everywhere last night is Schmidt the postie. And Schmidt’s plain mad.”

“Okay. But if you do see anyone else, just keep out of their way, will you Roger? You, and your mates. I’m serious. And can you tell my friend up in the apartments the same thing? She’ll probably be in either room 4A or her own room next door.”

“You mean the kike piece of ass?”

“Wish you’d stop talking like that. Her name’s Barbara Eshel. And you can also tell her that I’m going to the Metropolitan Hospital?”

“The funny farm?” Roger laughed. “Sounds, my friend, like you’re heading for the exact right place.”

H

E TOOK LUNCH AS HE DROVE

down from the mountains—a bottle of soda and a jerky-dry ham roll he’d bought at the general store—then back down Arroyo Seco, along Brooklyn, and past all the industries and warehousing around the Western Lithograph Building. He parked the Delahaye by a fence along the rail sidings beside Boyle Heights. He sat there for a while. Should have done this years ago, Clark, he told himself, when it was about something more than a will-o’-the-wisp. But, as it usually was for most things in his experience, it was way too late. Up the road, he bought a fifty cent return to Norwalk at the station booth, the same way you would if you were going anywhere. It was a few minutes gone one o’clock.

The Los Angeles Metropolitan Hospital, otherwise known as the Met or Metro, lay in farmland south and east of the city. Most of the people who worked there had to commute from the city as April Lamotte had said she’d once done. The Met ran a two shift day that went from early afternoon to early morning and back—that way, the busy times of

wake up

and

bed

were handled by separate teams—and most of the people waiting on the platform were recognizably hospital workers; females in faded caps and capes, bulky males in stained coveralls.

Pretending a deep interest in the posters on the corrugated walls—

VOTE LIBERTY LEAGUE PROTECT AMERICAN PURITY

; Uncle Sam pointing a finger to ask,

ARE YOU LOYAL

?—he wandered in the direction of a cluster of men in off-brown uniforms at the far end. When the train pulled in, he got in with them in a Whites Only carriage and sat down opposite a guy of about his height and age.

“How much you making at the Met today?”

The guy frowned and put his paper down. He had the sort of pencil-thin mustache Clark often thought of growing himself. “Waddya think, bud? It’s fifty cents an hour, bring your own lunch.”

“And that snazzy uniform…” Clark was already reaching for his billfold. “Bet you have to pay for that yourself as well?”

He kept with the main crowd outside Norwalk Junction, where a clocktower rose from the cluster of buildings amid a large expanse of grounds surrounded by a tall chainlink fence. Big iron gates set within an arched gateway bearing some Latin civic motto were already open to let the new shift in and the old shift out. Collar up and head down in his frayed uniform with its

Los Angeles County Department of Health Cleaning Division

badge on the breast pocket, and the only thing which might get him mistaken for Daniel Lamotte being the glasses

—

without which he was starting to feel oddly naked—he clicked through a turnstile and headed on along the cracked concrete path.

Security at the Met was even laxer than he’d expected and it didn’t look as much like a hospital as he’d feared. There were fields, orchards, clusters of bungalows, and he could even see how the relatives of inmates could kid themselves that this was a rural haven, although the concrete bungalows looked like army blockhouses, and the bigger cluster of buildings ahead would have stood in for a scary feelie staged in Dracula’s castle.

He aimed for the relative bustle of the main clocktower building. No sign of any inmates here, nor any of that obvious hospital smell, but business-suited admin staff, nurses and many lesser functionaries dressed in uniforms like his own were coming and going up the wide front steps. No one paid him any notice as he pushed through swing doors into a high-ceilinged hall, where someone had conveniently left a mop and trolley parked beneath an old portrait of some guy in a powdered wig.

“Say,” he asked, blocking the passage of a portly nurse as he steered the trolley across the checkered floor, “someone told me there’s a mess down in old staff records needs clearing up. Got any idea which way I should go?”

The nurse rolled her eyes as if his question was the final straw, but pointed toward an elevator and muttered something about

basement

before she waddled on. He clanked back the elevator gate, backed in the mop trolley, dragged the hooked brass lever down to B, then slid it shut. Just as he dropped from sight, he noticed that a big black guy was standing beneath the old portrait and staring right across at him.

The trolley wheels squeaked and the soles of his shoes made tick-ticking sounds as he followed subterranean tunnels. He clicked on lights and tried the door of every room he came to, and there were a lot. He found insect piles of ruined typewriters, massive drums of cleaning fluid, cockroaches dying and scurrying in the leaky pools which had formed around equally large drums of some unbranded soup … He even found heaped piles of stained, belted outfits which he took at first to be some weird kind of military uniform before he realized they were straightjackets.

The tunnels got lower and darker, although at least that ghastly ruined-soup smell became less prevalent. Then he reached a final door. Like all the rest, it was unlocked. He pulled the electric lever and the lights on the far side gave a reluctant flicker through shrouds of cobweb across tall avenues of file-racked shelves.

The prospect looked daunting. Thank the Almighty, though, for the predictabilities of bureaucracy. Each of the shelves was neatly labeled and dated. There was

Requisitions of 1936

and

Inventories of 1930

, both of which sounded like the kind of musical that no longer got made. Not to mention

Lobotomies of 1935

and

Sterilizations of 1938

. Easing out the tightly packed files from the grit of years to peer at them in the dim light, a curious muttering rose in his head. He stifled a sneeze, then glanced around, daring any of the shadows to move. But all he could sense was his own presence, and these long low passages lined with the lost history of the Met.

He ran his hands along sagging rows of

Staff Records

through coatings of dust and mouse droppings until he reached

Salaries

. If April Lamotte had worked here, it would have been—what?—before the turn of the last decade? He found January for 1928. The damp-warped volume crackled opened. Everything was still hand-written in those days, the inks color-coded in neat columns for payments and deductions.