Walking with Abel (29 page)

Authors: Anna Badkhen

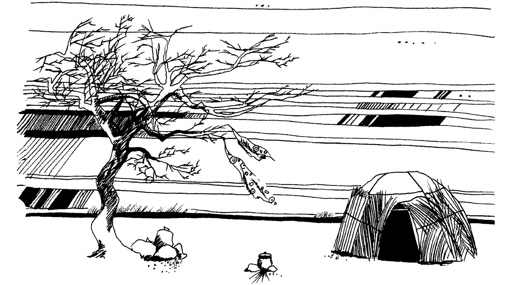

It was hot and there were no birds. There was a fairytale quality to everything: the song and the singers on their quest, the crackle of deadwood underfoot, the shrubs contorted to protect themselves from the hard white light. In the long ago, before Ballé became the staging point for migrating cattle, genii had lived in each of the sparse groves that studded the plateau. The most dangerous of all had been the genie that had made its home on the cliff where Oumarou’s father was buried. The Fulani said the cows had scared the genie away, that the genie had gone the way of hyenas and lions, but how could one know for sure? At this hour there were no cattle nearby. From time to time the girls called out each other’s names, just to make sure.

“Hairatou?”

“What?”

“Nothing!”

They walked on east. Deeper into the brambles and out into the open again, then into another low forest. They carried no knives and broke no branches. They gathered only deadfall. Some bits of wood Hairatou would not touch. “These are someone else’s,” she said.

Whose? How could she tell? Invisible borders crisscrossed the bush.

After they could barely close their arms around their bundles the girls tied them one last time and lifted them onto their heads and turned back toward the river, toward camp. Djamba sang again. She had packed her firewood smartly, her sticks almost uniformly straight. Hairatou’s bundle slightly more haphazard, lopsided on her head.

“Eh, girl! You pick crooked firewood, you’ll have a husband with a crooked thing!”

Hairatou did not respond. Her load was heavy and uncomfortable, and there was yet water to fetch from the river, for cooking. And she did not want to think about the thing of her future husband, a boy named al Hajj Oumarou Kuna, who was camping with his parents on the west bank of the river. On the very rare occasions she talked about him she covered her face with a scarf in modesty and a kind of awe. She never had spoken to him. That she even knew his name was an accident, something a careless girlfriend had let slip without thinking, because Hairatou’s father believed that it was better for the betrothed not to know the spouses their parents intended for them until the wedding day. Ideally, that also was the day they found out they had been betrothed in the first place. Such was the tradition, though in Oumarou’s view it applied particularly to boys.

As for Djamba’s own husband, Gouro, a son of Kumba and Saadou, she had not seen him for nearly two years. He and Djamba had been married only a few months when he asked his mother for a needle and thread to hem his best pants, ate a hearty breakfast, and jumped a bus first to Bamako, then to Côte d’Ivoire. Djamba had been in Djenné that morning, selling milk. He had been gone since. Whenever others discussed him in her presence Djamba would turn her head and look away. She never spoke of him, kindly or poorly. She was a proper Fulani woman, stoic and loyal. Gouro’s father had married him well.

—

A father had three obligations before his sons. The first was to give them names when they were born and pay for the naming ceremonies. The second was to decide where to have them circumcised and pay for the circumcisions. The third was to find them good wives and pay the bride price. Once a son was married he became an adult, responsible for his own family, for his own children.

The bride could not be Songhai, or Bambara, or Dogon, or rimaibe, or Bozo. She especially could not be Bwa, like the people who lived in Hayré, because the Bwa were pagans. She had to be a Fulani.

The bride had to be younger than the groom by at least three or four years. She had to come from a good, dignified, big family, and she had to be beautiful. She had to have grown up in the bush because that was where she would spend her life with her cowboy husband.

She could not be someone the boy already knew, someone about whom he had already had an opportunity to form an opinion. There had to be about a man’s future wife a mystery that he would discover gradually, in the course of his marriage.

The bride’s very existence had to be a mystery. “Until I find a bride I like and bring her here for my son I’ll tell him nothing,” Oumarou said. “When I bring her here I will tell him that he is getting married to this girl I picked for him.”

A boy who found out ahead of time which girl his father had selected for him might reject her. Other people could hear that and tell their friends, and through the rumor mill the girl and her parents inevitably would find out. That would upset the girl and embarrass both families.

Ousman met his bride Bobo on his wedding day. Neither had known that they had been engaged for three years. It was the same for Ousman’s older brother, Boucary, and it would be the same for Allaye and Hassan.

These were Oumarou’s rules, though he allowed for exceptions. Bomel, for example, married Adama, the son of Oumarou’s youngest brother, Allaye, who, like some fathers, preferred that his sons married relatives. Oumarou had agreed to the marriage, though he personally thought such a preference a little silly. “When your son marries a woman who is a stranger, she’s still a Fulani,” he said. “When they have children, the children will travel to their mother’s camp and so through them the two families will become one.”

Oumarou himself had married Fanta, who grew up in a village, not in the bush. But that was an exception, too, because he had been the widowed father of two small children, not in a position to wait for a wife who fit all his criteria. Also, Fanta did know the bush well. And she and Oumarou did love each other. In a good marriage, love mattered a lot.

Now Oumarou was making inquiries about a bride for Hassan. Discreetly he asked the Fulani men on transhumance about girls who met his requirements. Hassan’s mind, meanwhile, was on the cattle. Each night and each afternoon he drove his father’s cows to pasture and each morning and each evening he returned with a herd that looked thinner than before. Although Oumarou had said nothing to him about it, Hassan was holding himself responsible for taking the animals from the dwindling grasslands of the bourgou and bringing them too early to this vicious, arid plateau. He should have listened to his father and waited until it had rained more. He watched nearly in tears the clouds that gathered and dispersed overhead. If he could have jumped up there and wrung water out of the sky with his hands he would have.

—

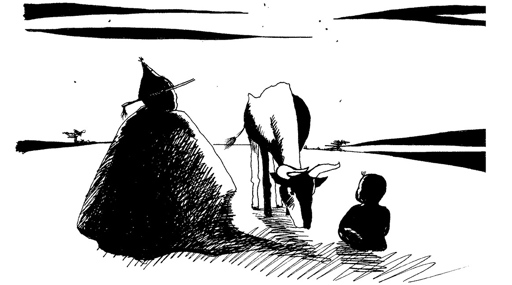

That evening Hassan drove the cows to camp in a cloud of dust. The animals walked right past the hitching rope at a hungry trot.

“Hairatou!” Ousman yelled. “Stop the cows!”

“Hairatou!” counterordered Oumarou. “Do your own work! Plenty of boys here.”

Allaye, who had been listening to music on his cellphone, reluctantly rose from his mat. Oumarou rose as well. Frustrated with the dust, the rainless sky, his feckless sons.

“Go away. You don’t know how to do it. You’ll never separate the cows from the calves.” He moved among the herd. In less than a minute the eight calves stood tethered to the rope in a neat line, the adult animals a few paces away. “See? This is how we do it.”

The sun was an angry eye in the cloud-blackened west. Then it was gone. Ousman set some manure and straw to smolder over the hearth where Hairatou was cooking millet and carried that slow fire in his bare hands and laid it among the herd, to keep away mosquitoes. He wrapped a plastic bag around his right hand and drenched it in pesticide that smelled like paint thinner and with that he set to wiping the calves’ hind legs. Ticks had been bothering the cattle since they had arrived in Ballé. He hung the pesticide bottle on a rope from Oumarou’s thorn tree and rinsed his hands with water from the Bani and returned to the cows to milk.

Later he brought Afo to the calf rope to watch the cows breathe. He sat on his haunches before the herd and Afo sat naked on the hot ground next to him. Against a sky aglitter with shooting stars. Afo leaned into his father and sucked his thumb.

Night streamed down. Hairatou sang. After dinner and prayer, an owl shrieked in flight over the camp, looking for a child’s soul to steal.

T

he only man on the plateau who did not seem tormented by anxiety about rain was Allaye. He was too busy obsessing over the bewildering workings of the human heart. He was in love.

That week Allaye fancied a girl named Binta, whose family had made camp halfway between Ballé and Hayré. Every night since the Diakayatés had arrived in Ballé, Allaye would sneak out of his father’s camp and hike to see Binta. He would return at dawn, sated, exhausted, smiling, and sleep all day long. He did not talk about his escapades in front of his father.

“The old man will never accept such foolishness—to travel so far because of a woman!” he said. There was another problem. He wanted to marry Binta, but her parents had promised her to someone else. Maybe he should seek advice from a marabout? Or get her pregnant? And what would happen to her if she got pregnant but ended up having to marry the other man anyway?

“Oh, that’s simple,” said Gano. “If a girl has sex before marriage she goes to a marabout. The marabout opens a kola nut, puts a gris-gris inside, spits, and closes the lobes. The girl eats the kola nut and becomes a virgin again.” Gano has heard of many such incidents of restored maidenhood from women friends.

Allaye had no idea that his father already had found him a bride, a girl a few years his junior, who camped with her family on the Niger River upstream from Moura, near Diafarabé. He had been betrothed for a year, since before he had left for Côte d’Ivoire.

O

umarou was not sure about looking for a bride for Drissa, who yet had years of Islamic scholarship ahead of him. He did not know if it was the place of a cowboy father to find a bride for a marabout son.

I visited Drissa twice, once during the rainy season and once in late fall. A decade into his Islamic studies he squatted in a cinderblock shack without electricity in a grimy unpaved square on San’s outskirts. This was his madrassa. There was a dug well from which he and other talibs pulled water hand over hand with a leather bucket to drink and wash and do laundry. There were inkwells made of Vaseline jars from which they copied the Koran in neat penmanship. They wiped their styluses on their hair. The buildings were tagged with spraypaint in English:

MEN STIR DELBY

.

EXTRA-MEN CLAN

.

MEN STAR

. North of the square shredded black and blue plastic bags flew from a fence of dry thornbrush. From here the boys set out into the straight provincial streets of the town with plastic lunchpails and the old tuneless beggar ditty in Fulfulde: