Walls within Walls (14 page)

Read Walls within Walls Online

Authors: Maureen Sherry

Ray drove slowly, surrounded by people and activity. The area was bustling with life, the sidewalks clogged with people selling food, books, and jewelry. As Ray headed north up Lenox Avenue, he spouted out information as if he were their tour guide. “That's the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library. And around the corner at the Schomburg Center you can see the work of Aaron Douglas, the father of African American art. And there was this terrific poetâCountee Cullen; some of his poetry is on the walls. You kids should check it out someday.”

“Nice place,” Patrick said happily. He wished the car would move faster.

Ray asked, “Know why they called this area Sugar Hill?”

“Why?” asked CJ.

“Because during the Harlem Renaissance, in the 1920s, this area was full of people with ambition, people who were striving, people looking to live the sweet life.”

“Sweet like sugar?” asked Brid as she jotted this information into her pink notebook.

“Exactly,” said Ray, who seemed to be enjoying himself.

“Here is number 409 Edgecombe.” He turned toward Eloise, and Brid saw him give her a little wink. “A famous place.”

“Whoa,” said Brid, “now that's a fancy building.” Compared to the low-slung buildings around it, number 409 looked regal and enormous. “Did Guastavino build that?” she asked CJ.

He shook his head no. “This is where all that blues music was coming from, this building and the one up the streetâthat's where all the action was. That poet Countee Cullen and that painter Aaron Douglas lived here. Also Thurgood Marshall, who became the first African American justice of the Supreme Court. This was some building.”

The kids stared at the majestic three-part building, unsure what they were supposed to be looking for. “Where is that other apartment building you were telling us about, up the street?” CJ asked. It wasn't a Guastavino building, but he was still curious.

“Yeah, let me show you that one.” Ray eased down the

street and brought the car to a stop in front of number 555.

“Now Lena Horne, the actress, lived here. So did Joe Louis, the boxer; Paul Robeson, a famous singer and actor; Duke Ellington; and Count Basie! Imagine walking around inside that place. Probably had to be able to paint and sing just to be the doorman.”

Eloise laughed loudly; she seemed to adore Ray and his waterfall of information.

Brid wondered why Eloise was being so patient with Ray. This building was interesting, but since Guastavino had not built it, it couldn't hold a clue. “But Ray,” she said as she looked at her notes, “let's go down to 522 Lenox. CJ needs to get his homework done, and that building may be important.”

“This is really interesting,” CJ said, thinking of Langston Hughes and his “Weary Blues.” “You see, Ray, we're studying a builder, Rafael Guastavino. He and his son built a few places around here. Can we swing down Lenox to 139th and then to Grant's Tomb? Those were both places he built. Do you think we could drive over there?”

“Okay, okay, one place at a time.” Ray sighed. “But you have to admit this was some neighborhood in Langston Hughes's time.”

“It was in Post's time, too,” Eloise said wistfully. “And yes, we admit it.”

On West 139th Street, it only took a moment to see that the building listed in Brid's notebook, number 522 Lenox, was gone. A modern brick building stood in its place. CJ placed his head in his hands, wondering how they would ever find the symbol for the Hughes poem, while Brid tried to keep things upbeat.

“So, Ray,” said Brid, “let's try Grant's Tomb. It should be directly toward the Hudson River, at 122nd Street and Riverside Drive.”

“Why, thank you, miss,” said Ray. “You kids are really different than I was as a boy. I don't remember too many class projects I got this excited about.”

CJ gave Brid a look that told her to calm down. They trusted Ray, but they didn't want the news of their detective work spread all over the building, especially not to Mr. Torrio.

Brid kept her eyes wide open. She felt certain she would recognize any sort of symbol if she saw it. “I'm sure the Ulysses poem refers to Grant's Tomb, because how many guys named Ulysses were there?” she said to CJ. “I just know we will see something that will make sense to us.”

Ray had crossed Broadway and was nearly to Riverside Drive, when Eloise suddenly exclaimed, “Stop the car! There's something I have to show you.” They could see the magnificent dome of Grant's Tomb just across the street.

“Do we have to get sidetracked again?” Brid moaned.

“I cannot believe this is still here! I had forgotten about it entirely,” said Eloise. “Oh, yes, we have to get sidetracked.”

“What is still here?” Pat asked.

“It's the Amiable Child.”

“What's that?”

“Amiableâit means someone who is agreeable and good natured,” CJ said.

“So it's a kid who wants to please someone?” Patrick groaned. This did not sound like his type of kid at all.

They stopped on the far side of Riverside Drive at a small, gated garden. Eloise got out of the car, and the children followed, while Ray stayed inside. Directly in front of them stood an urn-shaped cement object behind iron bars. The kids suddenly realized it was a grave site.

“Are you kidding meâthere's someone buried here?” Brid asked.

“Read the inscription,” Eloise said. “Out loud, if you please.”

Dutifully, CJ read, “Erected to the Memory of an Amiable Child, St. Claire Pollock, Died 15 July 1797 in the Fifth Year of His Age.”

“This is a grave for a kid?” Brid asked.

“You see, children, this land was farm country back then,” Eloise said. “This little boy fell to his death from those high rocks. When his family sold their farm, they

asked that his grave never be touched. And so it wasn't. Can you imagine such a valuable piece of land not being developed? Even if a rule makes no financial sense, sometimes people will comply out of respect.”

“Kind of like not touching our walls?”

“Exactly. My father liked to come sit up here,” she said, motioning to the bench that looked out over the sparkling water of the Hudson River. “This was certainly a spot that meant something to my family.”

All of this sad talk was making CJ want to move on. “You know, there isn't a poem that refers to this place. We have to keep thinking of the poems and the places they remind you of. If certain poems remind you of places in New York that meant something to your dad, and if Guastavino built them, those are the places your dad is directing us to with his book of poems.”

Eloise put her hand on CJ's arm. “You're right!” she said brightly. “I never thought to look outside our apartment building, but now this makes so much sense to me. Maybe my father wanted to lead me back to the places we went together when Julian and I were very young,” said Eloise, “when our family was still together.” The children followed her eyes across to Grant's Tomb. “Shall we make our way over there?” she asked.

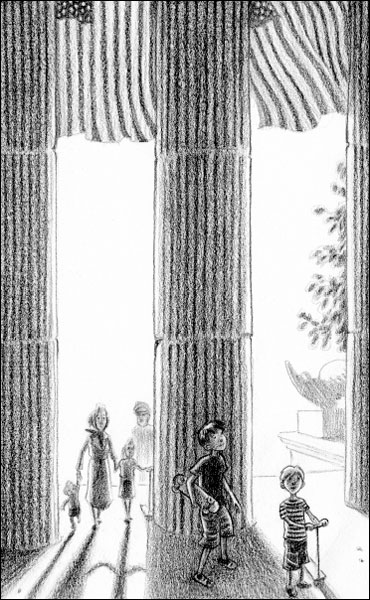

“Finally,” said Brid, and together they walked slowly to the impressive structure, looming large and round above the magnificent Hudson River.

Â

Â

“Who was this guy,” Patrick asked, “to get such a big gravestone?”

“The eighteenth president of the United States,” said Brid.

“And the leading Union general of the Civil War,” added CJ.

“And an ardent supporter of civil rights for African Americans,” said Eloise. “My father loved to come over hereâand to think I haven't visited since my childhood.”

Soaring, sloped roofs surrounded the entire mausoleum. The children stood back and took it all in.

Then Patrick piped up, “What sort of star is it called when it's shaped like that?” He pointed to a star mounted over the the center of the entrance.

“Duh, it's called a star,” Brid said.

“Well, actually, it's a general's star. Grant had several of them,” said Eloise.

“So that's the clue,” Pat said matter-of-factly.

“It's very difficult to say, Pat; there could be any number of symbols here,” Brid said.

“Yeah, but these other symbols aren't behind the wall,” said Pat.

“What?” Brid almost dropped her notebook. “Where behind the wall?”

“The part I can see some of, but can't get to,” said Pat.

“When did you see that?”

“I saw it when I went up in the dumbwaiter, but it's in a tight spot, between the Williamsons' apartment and that bad guy.”

“You mean Torrio?”

“I guess.”

“How did you see it?”

“I could only see some of it. It's a really big wooden thing; it looks like it has puzzle pieces, like a giant jigsaw, and I remember the star.”

“Why didn't you tell us?”

“Because I had all those letters on my arm, the letters from the other eye, and I thought that was the clue.”

“Well, it was, but you have to tell us everything!” said CJ. “Did it look like you could push the puzzle pieces?”

“Patrick, describe it!” Brid interrupted. “Tell us exactly what it looks like.”

“Well, it's brown and made out of wood, and the wood has lines in it.”

“What do you mean, lines?”

“Like a drawing or an outline.”

“Huh? I don't get it,” CJ said.

“Pat, why don't you draw it?” said Brid.

“Nope. Can't draw. It's like a Christmas stocking lying on its side, after you take out the presents.”

“So it's the shape of an empty stocking?”

“Yeah, but on its side.”

“Now, Patrick, dear,” said Eloise, “I really know those walls. And I know we used to have a carved wooden mural, but I am not sure I've ever seen anything like that.”

“Yeah, but you can't fit in there, because it's on the inside of the wall. That's why you didn't see it. You have to look at it sideways to see it in there, and the only way you can do that is to be inside the dumbwaiter. Guess that dumbwaiter's not so dumb!”

Everyone was staring at Pat, and it was only then that CJ realized Ray had joined them and was listening to the whole conversation.

“Whoa, guess we aren't talking about a homework assignment anymore?” Ray looked a little sad, as if he had been left out or used.

“No, Ray, I'm afraid we've kept you in the dark,” Eloise said.

“I'm guessing we're back to treasure hunting, Eloise?”

“Forgive me, Ray.”

She turned to the children. “Ray and I have had so many false leads in the past that he made me promise just to let it go.”

“What are the chances that it's at 2 East 92nd Street? Almost none, if you ask me,” Ray said.

“But Ray, with all respect, this time we aren't asking you. I know you are going to laugh at me, but these kids are really on to something.”

Brid turned to CJ. “Servantâ¦dumbwaiterâ¦

Gustavino! Are you thinking what I'm thinking?”

“You mean, maybe the symbols we need to push aren't actually on the structures? Like, maybe there is a symbol for each structure behind the wall, and that's what we push?” CJ replied.

Eloise smiled. “Maybe I need to go see that carved wooden installation before we go see any more Guastavino buildings.”

“Exactly,” said CJ.

“But how do we get inside the wall?” asked Brid.

“Now, children,” interrupted Eloise, “I will not permit you to climb behind the wall. It's too risky. I simply won't permit it.”

“I've

got

it!” shouted Brid. Dramatically, she flipped back many pages in her notebook. “This plan is flawless,” she said. “We will get behind that wall.”

Normal life kept interfering with their detective work. On Monday morning, their dad left for his business trip to China. Their mom was busy trying to find a preschool for Carron and seemed preoccupied at breakfast.

That day after school, CJ had his first friend over from Saint James's. His name was Brent, and he was CJ's science lab partner. For a kid from a fancy family, he didn't act or look fancy. He had thick blond hair that shrouded his blue eyes. His shirt was mostly untucked, and his tie was pulled askew.

Brent knew a lot about different things. Even though he was rich like the other kids, he was fun to be around. Instead of a nanny like the other kids, he had a mannyâa man.

Brent had asked for the playdate, and when CJ said okay, Brent had the manny set it up. He never even had to ask his parents.

“You guys want to stop in the park and shoot some hoops?” the manny asked when they left the school. So they played basketball for a while, until Brent suggested they go to CJ's house, which was just two blocks away. The manny was tall and African American. With his perfect teeth, chiseled body, and the way he was always being upbeat, he reminded CJ of a talk show host. Brent told CJ that the manny wanted to be an actor, and he sometimes left Brent in odd places while he auditioned for a movie or a play. Brent didn't mind at all.

“My dad's never home,” said Brent. “So this is the next best thing, 'cause we do guy stuff, and he's really good at my homework.”

CJ didn't want to ask about the manny doing the homework, because Brent was pretty capable in science lab. He also didn't want to talk to Brent about his own missing dad, as he was certain this was a temporary thing. Once Bruce Smithfork got that factory opened in China, he would resume being his old self. CJ hoped.

When the three guys got to CJ's house, the manny told Brent he would be back in an hour. They did some complicated secret handshake, then the manny turned and left.

“Where's he going?” asked CJ.

“He mostly talks to girls,” Brent said. “At least that's what he tells me.”

The apartment was mercifully quiet, the other kids all out with Maricel. “Wanna play some cards?” Brent asked.

“Uh, okay,” said CJ, not really into it. They pulled CJ's desk to the middle of the room, and CJ was glad he had hung a poster over the grille so the eye wouldn't peek out at them. Brent took the seat facing the door. CJ shuffled, letting the cards fan his face before he dealt.

“What's with the dot writing?” Brent asked casually.

“What?” replied CJ, startled.

“The dot writing, like they used in the late eighteen hundreds. It's all around your room.” Brent pointed at the poem that wrapped around the moldings.

“They're poems,” said CJ. “The guy who lived here was really into poetry and had them written like that in the moldings.”

“No, I mean the dots have a message. You see how certain letters have a tiny dot over them? You just put them in order and then check out what they spell. So what does that one spell?” Brent said, staring at the eastern wall.

CJ was embarrassed that he'd never even noticed the tiny dots. “I never really looked at them.”

“Really? Well, let's check them out.”

Brent had already pulled a piece of paper out of his backpack and was writing down the letters that had a dot above them. The dots were small, almost like a pinprick.

Still, CJ wondered how he had missed them.

While Brent wrote, CJ worried about their secret. He had to keep Brent out of the other rooms, or he'd see the poetry on the moldings there. What if he knew something about the Post family fortune?

Brent was talking. “You see, back in England, people hated paying postage to the government. So they started to mail newspapers to one another for free. They would just put a dot beneath the letters of the words they wanted to write, and that gave them a free way to communicate with others.” He seemed to like the same sort of arcane information CJ liked.

“That makes no sense. If postage was expensive, how could they mail newspapers for free?”

“Because the law was that anything with a government stamp on it could be mailed for free because they paid a government tax.”

CJ thought that if this kid weren't so nosy, he might actually like him. “I'm sure this isn't anything like that.”

Brent read the poem. “Let's see. I think Carl Sandburg wrote this:

Arithmetic is where numbers fly like pigeons in and out of your head.

Arithmetic tells you how many you lose or win if you

know how many you had before you lost or won.

Arithmetic is seven eleven all good children go to heavenâ

or five six bundle of sticks.

Arithmetic is numbers you squeeze from your head to your handâ

And there the poem stopped. CJ thought the artist had simply run out of wall.

When Brent wrote the letters with a dot under them, it looked like this:

Â

INSILVERROOM

Â

“Dude!” exclaimed Brent, who CJ was beginning to not like at all anymore. “What's in the silver room?”

“Oh, that!” CJ said, thinking quickly. “There used to be a silver room here, but it was covered over years ago,” he said, wondering what could be in the silver room. Was there access to the wooden mural through there?

“I thought my grandmother was the only one who still had a silver room.”

“Really? What does she use it for?”

“She has a lot of parties, and I guess it's an easier way to keep things organized. She does an inventory of all her silverware before and after, and she has people shining stuff all the time in there.”

Both boys jumped at the buzzer. CJ ran down the hallway to answer it, closing Brid's, Carron's, and Patrick's doors on the way. He didn't want Brent snooping

and finding any other messages.

He buzzed the intercom. “Hello?”

“Got a guy named Manny here, asking for someone named Brent,” said Ray.

“I'll send him down.”

Brent had followed CJ down the hall. “Time to go, Brent,” said CJ. “Your manny guy is here.”

“Dude, he can wait.”

“He said it's important you meet him downstairs right away.”

“So you just stay home all by yourself?” Brent asked with wide eyes. “We can wait with you.”

“No, you need to leave. Now!” CJ was surprised at the sound of his voice, and he felt a little badly that Brent was getting his jacket on, grabbing his backpack, and practically running to the elevator.

“See you at school tomorrow,” CJ said, with some apology in his voice.

“Yeah, whatever,” came Brent's deflated reply.

As soon as he heard the door shut, CJ ran into Patrick's room. The poem on his moldings also had little marks over certain letters, but instead of dots, some words had numbers. Guessing he had to order the letters by these numbers, he quickly wrote down the poem, one he had never heard of.

For me, me, me.

It has a little shelf, my dear,

For me, me, me.

But when CJ wrote them out in the order of the numbers he got:

Â

NIPAMEHTHSUP

Â

What is that supposed to mean? thought CJ. He wished he hadn't kicked Brent out quite so quickly. His thoughts were interrupted by a ruckus at the front door as Maricel came home with the other three children.

Patrick came bounding into his room. “Oh, hey,” he said. Patrick never seemed to mind when others used his stuff. “Wanna play with me?” he asked as he pulled out his wrestling figures.

“No, I was just writing some things down,” CJ said as Patrick leaned over his shoulder.

Patrick studied the jumble of letters. “So what map do you want to push in?” he asked.

CJ looked at him, stunned.

“What are you talking about?”

“What map do you need to push in?”

“What are you saying?”

“What you just wrote about pushing the map in. What map?”

“Patrick, I have no idea what you are saying.”

“I'm not saying it. You're the one who wrote it and now you won't even tell me why and you're in my room writing stuff, so you should tell me!”

CJ looked again at his paper. “Show me where you see that?”

“So easy.” Patrick swept his finger right to left across the lettering. “Just read it backward. It says, âPush the map in,' and by the way, CJ, you write with no finger spaces, which is really, really bad.”

Watching Patrick, CJ thought his little brother might be smarter than any of them.

“Hey, Patrick?”

“Yup.”

“That big thing you saw behind the wall, that wooden thing with lines that looked like a Christmas stocking on its side?”

“Yup.”

CJ pulled his brother down the hall and pointed to the map of Manhattan he had pinned to his bedroom door. “Would you say it looks like this shape?” he asked.

“Totally.”