War Horse

MICHAEL MORPURGO

War Horse

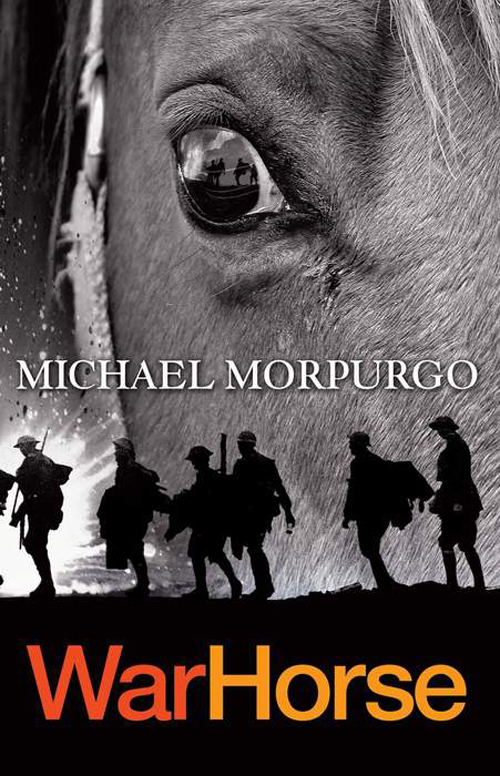

Text copyright © 1982 Michael Morpurgo

Cover copyright © 2006 from the poster for the National Theatre's stage adaptation of War Horse, playing from October 2007

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Egmont UK Ltd

239 Kensington High Street

London

W8 6SA

Visit our web site at www.egmont.co.uk

First e-book edition 2010

ISBN 978 1 4052 4933 1

For Lettice

Many people have helped me in the writing of this book. In particular I want to thank Clare and Rosalind, Sebastian and Horatio, Jim Hindson (veterinary surgeon), Albert Weeks, the late Wilfred Ellis and the late Captain Budgett – all three octogenarians in the parish of Iddesleigh.

IN THE OLD school they use now for the Village Hall, below the clock that has stood always at one minute past ten, hangs a small dusty painting of a horse. He stands, a splendid red bay with a remarkable white cross emblazoned on his forehead and with four perfectly matched white socks. He looks wistfully out of the picture, his ears pricked forward, his head turned as if he has just noticed us standing there.

To many who glance up at it casually, as they might do when the hall is opened up for Parish meetings, for harvest suppers or evening socials, it is merely a tarnished old oil painting of some unknown horse by a competent but anonymous artist. To them the picture is

so familiar that it commands little attention. But those who look more closely will see, written in fading black copperplate writing across the bottom of the bronze frame:

Joey.

Painted by Captain James Nicholls, autumn 1914.

Some in the village, only a very few now and fewer as each year goes by, remember Joey as he was. His story is written so that neither he nor those who knew him, nor the war they lived and died in, will be forgotten.

MY EARLIEST MEMORIES are a confusion of hilly fields and dark, damp stables, and rats that scampered along the beams above my head. But I remember well enough the day of the horse sale. The terror of it stayed with me all my life.

I was not yet six months old, a gangling, leggy colt who had never been further than a few feet from his mother. We were parted that day in the terrible hubbub of the auction ring and I was never to see her again. She was a fine working farm horse, getting on in years but with all the strength and stamina of an Irish draught horse quite evident in her fore and hind quarters. She was sold within minutes, and before I

could follow her through the gates, she was whisked out of the ring and away. But somehow I was more difficult to dispose of. Perhaps it was the wild look in my eye as I circled the ring in a desperate search for my mother, or perhaps it was that none of the farmers and gypsies there were looking for a spindly-looking half-thoroughbred colt. But whatever the reason they were a long time haggling over how little I was worth before I heard the hammer go down and I was driven out through the gates and into a pen outside.

‘Not bad for three guineas, is he? Are you, my little firebrand? Not bad at all.’ The voice was harsh and thick with drink, and it belonged quite evidently to my owner. I shall not call him my master, for only one man was ever my master. My owner had a rope in his hand and was clambering into the pen followed by three or four of his red-faced friends. Each one carried a rope. They had taken off their hats and jackets and rolled up their sleeves; and they were all laughing as they came towards me. I had as yet been touched by no man and backed away from them until I felt the bars of the pen behind me and could go no further. They seemed to lunge at me all at once, but they were slow and I managed to slip past them and into the middle of the

pen where I turned to face them again. They had stopped laughing now. I screamed for my mother and heard her reply echoing in the far distance. It was towards that cry that I bolted, half charging, half jumping the rails so that I caught my off foreleg as I tried to clamber over and was stranded there. I was grabbed roughly by the mane and tail and felt a rope tighten around my neck before I was thrown to the ground and held there with a man sitting it seemed on every part of me. I struggled until I was weak, kicking out violently every time I felt them relax, but they were too many and too strong for me. I felt the halter slip over my head and tighten around my neck and face. ‘So you’re quite a fighter, are you?’ said my owner, tightening the rope and smiling through gritted teeth. ‘I like a fighter. But I’ll break you one way or the other. Quite the little fighting cock you are, but you’ll be eating out of my hand quick as a twick.’

I was dragged along the lanes tied on a short rope to the tailboard of a farm cart so that every twist and turn wrenched at my neck. By the time we reached the farm lane and rumbled over the bridge into the stable yard that was to become my home, I was soaked with exhaustion and the halter had rubbed my face raw. My

one consolation as I was hauled into the stables that first evening was the knowledge that I was not alone. The old horse that had been pulling the cart all the way back from market was led into the stable next to mine. As she went in she stopped to look over my door and nickered gently. I was about to venture away from the back of my stable when my new owner brought his crop down on her side with such a vicious blow that I recoiled once again and huddled into the corner against the wall. ‘Get in there you old ratbag,’ he bellowed. ‘Proper nuisance you are Zoey, and I don’t want you teaching this young ’un your old tricks.’ But in that short moment I had caught a glimpse of kindness and sympathy from that old mare that cooled my panic and soothed my spirit.

I was left there with no water and no food while he stumbled off across the cobbles and up into the farm-house beyond. There was the sound of slamming doors and raised voices before I heard footsteps running back across the yard and excited voices coming closer. Two heads appeared at my door. One was that of a young boy who looked at me for a long time, considering me carefully before his face broke into a beaming smile. ‘Mother,’ he said deliberately. ‘That will be a wonderful

and brave horse. Look how he holds his head.’ And then, ‘Look at him, Mother, he’s wet through to the skin. I’ll have to rub him down.’

‘But your father said to leave him, Albert,’ said the boy’s mother. ‘Said it’ll do him good to be left alone. He told you not to touch him.’

‘Mother,’ said Albert, slipping back the bolts on the stable door. ‘When father’s drunk he doesn’t know what he’s saying or what he’s doing. He’s always drunk on market days. You’ve told me often enough not to pay him any account when he’s like that. You feed up old Zoey, Mother, while I see to him. Oh, isn’t he grand, Mother? He’s red almost, red-bay you’d call him, wouldn’t you? And that cross down his nose is perfect. Have you ever seen a horse with a white cross like that? Have you ever seen such a thing? I shall ride this horse when he’s ready. I shall ride him everywhere and there won’t be a horse to touch him, not in the whole parish, not in the whole county.’

‘You’re barely past thirteen, Albert,’ said his mother from the next stable. ‘He’s too young and you’re too young, and anyway father says you’re not to touch him, so don’t come crying to me if he catches you in there.’

‘But why the divil did he buy him, Mother?’ Albert asked. ‘It was a calf we wanted, wasn’t it? That’s what he went in to market for, wasn’t it? A calf to suckle old Celandine?’

‘I know dear, your father’s not himself when he’s like that,’ his mother said softly. ‘He says that Farmer Easton was bidding for the horse, and you know what he thinks of that man after that barney over the fencing. I should imagine he bought it just to deny him. Well that’s what it looks like to me.’

‘Well I’m glad he did, Mother,’ said Albert, walking slowly towards me, pulling off his jacket. ‘Drunk or not, it’s the best thing he ever did.’

‘Don’t speak like that about your father, Albert. He’s been through a lot. It’s not right,’ said his mother. But her words lacked conviction.

Albert was about the same height as me and talked so gently as he approached that I was immediately calmed and not a little intrigued, and so stood where I was against the wall. I jumped at first when he touched me but could see at once that he meant me no harm. He smoothed my back first and then my neck, talking all the while about what a fine time we would have together, how I would grow up to be the smartest horse

in the whole wide world, and how we would go out hunting together. After a bit he began to rub me gently with his coat. He rubbed me until I was dry and then dabbed salted water onto my face where the skin had been rubbed raw. He brought in some sweet hay and a bucket of cool, deep water. I do not believe he stopped talking all the time. As he turned to go out of the stable I called out to him to thank him and he seemed to understand for he smiled broadly and stroked my nose. ‘We’ll get along, you and I,’ he said kindly. ‘I shall call you Joey, only because it rhymes with Zoey, and then maybe, yes maybe because it suits you. I’ll be out again in the morning – and don’t worry, I’ll look after you. I promise you that. Sweet dreams, Joey.’

‘You should never talk to horses, Albert,’ said his mother from outside. ‘They never understand you. They’re stupid creatures. Obstinate and stupid, that’s what your father says, and he’s known horses all his life.’

‘Father just doesn’t understand them,’ said Albert. ‘I think he’s frightened of them.’

I went over to the door and watched Albert and his mother walking away and up into the darkness. I knew then that I had found a friend for life, that there was an

instinctive and immediate bond of trust and affection between us. Next to me old Zoey leant over her door to try to touch me, but our noses would not quite meet.

THROUGH THE LONG hard winters and hazy summers that followed, Albert and I grew up together. A yearling colt and a young lad have more in common than awkward gawkishness.

Whenever he was not at school in the village, or out at work with his father on the farm, he would lead me out over the fields and down to the flat, thistly marsh by the Torridge river. Here on the only level ground on the farm he began my training, just walking and trotting me up and down, and later on lunging me first one way and then the other. On the way back to the farm he would allow me to follow on at my own speed, and I learnt to come at his whistle, not out of obedience but

because I always wanted to be with him. His whistle imitated the stuttering call of an owl – it was a call I never refused and I would never forget.

Old Zoey, my only other companion, was often away all day ploughing and harrowing, cutting and turning out on the farm and so I was left on my own much of the time. Out in the fields in the summer time this was bearable because I could always hear her working and call out to her from time to time, but shut in the lone-liness of the stable in the winter, all day could pass without seeing or hearing a soul, unless Albert came for me.

As Albert had promised, it was he who cared for me, and protected me all he could from his father; and his father did not turn out to be the monster I had expected. Most of the time he ignored me and if he did look me over, it was always from a distance. From time to time he could even be quite friendly, but I was never quite able to trust him, not after our first encounter. I would never let him come too close, and would always back off and shy away to the other end of the field and put old Zoey between us. On every Tuesday however, Albert’s father could still be relied upon to get drunk, and on his return Albert would often find some pretext

to be with me to ensure that he never came near me.

On one such autumn evening about two years after I came to the farm Albert was up in the village church ringing the bells. As a precaution he had put me in the stable with old Zoey as he always did on Tuesday evenings. ‘You’ll be safer together. Father won’t come in and bother you, not if you’re together,’ he’d say, and then he’d lean over the stable door and lecture us about the intricacies of bell-ringing and how he had been given the big tenor bell because they thought he was man enough already to handle it and that in no time he’d be the biggest lad in the village. My Albert was proud of his bell-ringing prowess and as Zoey and I stood head to tail in the darkening stable, lulled by the six bells ringing out over the dusky fields from the church, we knew he had every right to be proud. It is the noblest of music for everyone can share it – they have only to listen.

I must have been standing asleep for I do not recall hearing him approach, but quite suddenly there was the dancing light of a lantern at the stable door and the bolts were pulled back. I thought at first it might be Albert, but the bells were still ringing, and then I heard the voice that was unmistakably that of Albert’s father

on a Tuesday night after market. He hung the lantern up above the door and came towards me. There was a whippy stick in his hand and he was staggering around the stable towards me.

‘So, my proud little devil,’ he said, the threat in his voice quite undisguised. ‘I’ve a bet on that I can’t have you pulling a plough inside a week. Farmer Easton and the others at The George think I can’t handle you. But I’ll show ’em. You’ve been molly-coddled enough, and the time has come for you to earn your keep. I’m going to try some collars on you this evening, find one that fits, and then tomorrow we’ll start ploughing. Now we can do it the nice way or the nasty way. Give me trouble and I’ll whip you till you bleed.’

Old Zoey knew his mood well enough and whinnied her warning, backing off into the dark recesses of the stable, but she need not have warned me for I sensed his intention. One look at the raised stick sent my heart thumping wildly with fear. Terrified, I knew I could not run, for there was nowhere to go, so I put my back to him and lashed out behind me. I felt my hooves strike home. I heard a cry of pain and turned to see him crawling out of the stable door dragging one leg stiffly behind him and muttering words of cruel vengeance.

That next morning both Albert and his father came out together to the stables. His father was walking with a pronounced limp. They were carrying a collar each and I could see that Albert had been crying for his pale cheeks were stained with tears. They stood together at the stable door. I noticed with infinite pride and pleasure that my Albert was already taller than his father whose face was drawn and lined with pain. ‘If your mother hadn’t begged me last night, Albert, I’d have shot that horse on the spot. He could’ve killed me. Now I’m warning you, if that animal is not ploughing straight as an arrow inside a week, he’ll be sold on, and that’s a promise. It’s up to you. You say you can deal with him, and I’ll give you just one chance. He won’t let me go near him. He’s wild and vicious, and unless you make it your business to tame him and train him inside that week, he’s going. Do you understand? That horse has to earn his keep like everyone else around here – I don’t care how showy he is – that horse has got to learn how to work. And I’ll promise you another thing, Albert, if I have to lose that bet, then he has to go.’ He dropped the collar on the ground and turned on his heel to go.

‘Father,’ said Albert with resolution in his voice. ‘I’ll

train Joey – I’ll train him to plough all right – but you must promise never to raise a stick to him again. He can’t be handled that way, I know him, Father. I know him as if he were my own brother.’

‘You train him, Albert, you handle him. Don’t care how you do it. I don’t want to know,’ said his father dismissively. ‘I’ll not go near the brute again. I’d shoot him first.’

But when Albert came into the stable it was not to smoothe me as he usually did, nor to talk to me gently. Instead he walked up to me and looked me hard in the eye. ‘That was divilish stupid,’ he said sternly. ‘If you want to survive, Joey, you’ll have to learn. You’re never to kick out at anyone ever again. He means it, Joey. He’d have shot you just like that if it hadn’t been for Mother. It was Mother who saved you. He wouldn’t listen to me and he never will. So never again Joey. Never.’ His voice changed now, and he spoke more like himself. ‘We have one week Joey, only one week to get you ploughing. I know with all that thoroughbred in you you may think it beneath you, but that’s what you’re going to have to do. Old Zoey and me, we’re going to train you; and it’ll be divilish hard work – even harder for you ’cos you’re not quite the right shape for

it. There’s not enough of you yet. You won’t much like me by the end of it, Joey. But Father means what he says. He’s a man of his word. Once he’s made up his mind, then that’s that. He’d sell you on, even shoot you rather than lose that bet, and that’s for sure.’

That same morning, with the mists still clinging to the fields and linked side by side to dear old Zoey in a collar that hung loose around my shoulders, I was led out on to Long Close and my training as a farmhorse began. As we took the strain together for the first time the collar rubbed at my skin and my feet sank deep into the soft ground with the effort of it. Behind, Albert was shouting almost continuously, flashing a whip at me whenever I hesitated or went off line, whenever he felt I was not giving it my best – and he knew. This was a different Albert. Gone were the gentle words and the kindnesses of the past. His voice had a harshness and a sharpness to it that would brook no refusal on my part. Beside me old Zoey leant into her collar and pulled silently, head down, digging in with her feet. For her sake and for my own sake, for Albert’s too, I leant my weight into my collar and began to pull. I was to learn during that week the rudiments of ploughing like a farm horse. Every muscle I had ached with the strain of

it; but after a night’s good rest stretched out in the stable I was fresh again and ready for work the next morning.

Each day as I progressed and we began to plough more as a team, Albert used the whip less and less and spoke more gently to me again, until finally at the end of the week I was sure I had all but regained his affection. Then one afternoon after we had finished the headland around Long Close, he unhitched the plough and put an arm around each of us. ‘It’s all right now, you’ve done it my beauties. You’ve done it,’ he said. ‘I didn’t tell you, ’cos I didn’t want to put you off, but Father and Farmer Easton have been watching us from the house this afternoon.’ He scratched us behind the ears and smoothed our noses. ‘Father’s won his bet and he told me at breakfast that if we finished the field today he’d forget all about the incident, and that you could stay on, Joey. So you’ve done it my beauty and I’m so proud of you I could kiss you, you old silly, but I won’t do that, not with them watching. He’ll let you stay now, I’m sure he will. He’s a man of his word is my father, you can be sure of that – long as he’s sober.’

It was some months later, on the way back from cutting the hay in Great Meadow along the sunken

leafy lane that led up into the farmyard that Albert first talked to us of the war. His whistling stopped in midtune. ‘Mother says there’s likely to be a war,’ he said sadly. ‘I don’t know what it’s about, something about some old Duke that’s been shot at somewhere. Can’t think why that should matter to anyone, but she says we’ll be in it all the same. But it won’t affect us, not down here. We’ll go on just the same. At fifteen I’m too young to go anyway – well that’s what she said. But I tell you Joey, if there is a war I’d want to go. I think I’d make a good soldier, don’t you? Look fine in a uniform, wouldn’t I? And I’ve always wanted to march to the beat of a band. Can you imagine that, Joey? Come to that, you’d make a good war horse yourself, wouldn’t you, if you ride as well as you pull, and I know you will. We’d make quite a pair. God help the Germans if they ever have to fight the two of us.’

One hot summer evening, after a long and dusty day in the fields, I was deep into my mash and oats, with Albert still rubbing me down with straw and talking on about the abundance of good straw they’d have for the winter months, and about how good the wheat straw would be for the thatching they would be doing, when I heard his father’s heavy steps coming across the yard

towards us. He was calling out as he came. ‘Mother,’ he shouted. ‘Mother, come out Mother.’ It was his sane voice, his sober voice and was a voice that held no fear for me. ‘It’s war, Mother. I’ve just heard it in the village. Postman came in this afternoon with the news. The devils have marched into Belgium. It’s certain for sure now. We declared war yesterday at eleven o’clock. We’re at war with the Germans. We’ll give them such a hiding as they won’t ever raise their fists again to anyone. Be over in a few months. It’s always been the same. Just because the British lion’s sleeping they think he’s dead. We’ll teach them a thing or two, Mother – we’ll teach them a lesson they’ll never forget.’

Albert had stopped brushing me and dropped the straw on the ground. We moved over towards the stable door. His mother was standing on the steps by the door of the farmhouse. She had her hand to her mouth. ‘Oh dear God,’ she said softly. ‘Oh dear God.’