Watch Me: A Memoir (24 page)

Read Watch Me: A Memoir Online

Authors: Anjelica Huston

Tags: #actress, #Biography & Autobiography, #movie star, #Nonfiction, #Personal Memoir, #Retail

Often, after the evening screenings some jury members would have dinner together and wind up at the Carlton Hotel in the suite the producer Jeremy Thomas, his wife, Eski, and

his business partner, Hercules Bellville, shared with Bernardo and Clare, and talk freely about the films in competition. Hercules wore black velvet Chinese slippers and sometimes a little wooden bow tie. Herky was now working with Jeremy Thomas at the Recorded Picture Company. Jeremy’s suite was the hub of the party, the heart of the festival. All the cool people congregated there in the after hours.

At our closing deliberations, there was a full-on lunch buffet and a bank of seafood, including a large poached salmon on the bone. As we were eating, Bernardo rose fretfully from the table and backed toward the window, waving his napkin. “There’s a bone in my throat,” he gasped. Soon all the women in the jury were staring down Bernardo’s throat. As I ran past him to go upstairs and get my tweezers, Aleksei stopped me and said, “I wish I had a bone in

my

throat.”

Bernardo was taken to a nearby hospital and attended to. That afternoon we were whisked away from the Majestic in a fleet of Citroëns and taken to a castle in the hills above Cannes, where we were to cast our final votes, then change into our evening dress—in my case, a sleeveless black velvet, lace, and yellow taffeta confection designed by the Emanuels. Mira Nair was in full sari with pendant earrings and a bindi on her forehead. Fanny Ardant was a vision in black Dior tulle and diamonds. We made the descent from the hills surrounded by gendarmes, traveling rapidly with sirens wailing, in a full motorcade to the Grand Palais du Festival to announce the winners. The Palme d’Or was awarded to

Wild at Heart.

The night after the festival, I went with Prince Albert to dinner at a delicious and proper restaurant in Èze, a drive out from Cannes in his sports car. I had worn high heels, which

was gauche, because the little medieval streets of Èze are made of cobblestone. On our drive, his bodyguards accompanied us in two cars, front and rear.

Dinner was a bit stiff. Prince Albert was very nice, but I wasn’t sure we had too much in common. After dinner, I clattered down the steep cobblestone incline to his car. As we made a wide turn, the bay of Nice shimmered before us in the sunset. He pulled over to the side of the road, opened the passenger door for me, and gave me a surprisingly ardent kiss with the bodyguards looking on, which I found quite disconcerting.

PART THREE

FORTUNE

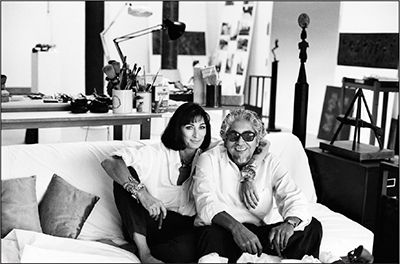

Photographed by Brigitte Lacombe

CHAPTER 23

A

lthough I may have wished for the obvious in my relationships—mutuality, sharing, caring, and fidelity—the hard reality was that these were qualities that did not necessarily turn me on. I’ve always been attracted to cowboys and rock stars, artists and wild men. Men you can’t depend on. Guys who have you waiting by the telephone—not, for the most part, the kind and easy ones you can relax around.

And then I met Robert Graham. Bob was Mexican but took his name from his Scottish grandfather. Bob was a famous sculptor, known for his massive bronze works. A mutual friend, Earl McGrath, who happened to be both an art dealer and the manager of the Rolling Stones, had told me that Bob was crazy about me and told Bob that I was crazy about him. Neither of us had any idea.

On June 23, 1990, Bob and his driver, Nick, picked me up in his long gunmetal-gray limousine on the way to Earl McGrath’s for a dinner one Gay Pride weekend in West Hollywood. Bob didn’t like to drive, he said; he got distracted. Tall and handsome, Bob had a steel-and-silver mane of thick shoulder-length hair that he wore either in a Japanese sumo twist at the nape of his neck or in a ponytail, and a small goatee. His skin was more café than lait. His eyes were dark as teak. He watched me over the rims of his blue-tinted shades.

Bob was ultra-cool. He moved with ease and grace. After dinner, we climbed the stairs to Earl’s rooftop to watch the fireworks. I looked over at Bob and thought, “Hmm, I wonder.” It was a strange feeling, being around him. There was a strong attraction but also a feeling of destiny.

When we drove back to my house that June night, I was nervous and didn’t ask Bob in. I could tell he was a little surprised. “I’ll call you tomorrow,” he said. Thirty minutes later, he called me from the car on his way home. “Will you come to my studio on Sunday?” he asked. “I’d like to show you my work.”

On Sunday I put on a dress I’d bought years before on a trip to Hawaii, black and white and flimsy, made of silk scarves stitched together, and drove myself and my dog, Minnie, down to Venice. It was a beautiful, fresh, windy day, the sun glinting off the ocean. There was a chill in the air. We had lunch and walked on the beach. Bob told me he wasn’t taking off his shoes; he didn’t like to walk barefoot.

We came to a stop and sat down. When I rolled over to lie on my stomach on the sand, the wind came up and blew the skirt of my dress over my head, exposing my underwear. With the hint of a smile, Bob simply reached over and caught the hem of the dress and pulled it back down without a word. I thought that was very courtly of him. Then we went back to his studio and made love.

I was amazed by Bob’s work. My friend Greta and I had first seen his bronze gateway, standing twenty-five feet, a colossal sculpture of two headless naked athletes, at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on the opening day of the 1984 Summer Olympics. During those high bright days of July, inside the Coliseum, the physiques of the women runners

had never looked so strong or so muscular. And the sight of those beautiful superwomen, with their red USA uniforms and their gleaming black skin, their dreads and their gold jewelry glittering in the sun, proved that the Graham sculpture was no exaggeration.

When I asked Bob about the pieces, he said, “I sculpted what I saw.”

As I came to know him and to understand his process, I saw that it was the relentless and irresistible challenge to perfect his craft that drove him. I saw him destroy work that failed to be faithful in some way to its subject. Bob never cheated, never took the easy way. The work was everything. His hands were the means by which he expressed himself; they were his voice.

Bob told me about growing up in Mexico with his three mothers—his actual mother, his aunt, and his grandmother. Bob grew up under the impression that his father had died; that was what his mother had always claimed. But then, on his twelfth birthday, a strange man had come to his house and taken him out to lunch. During the meal, he told Bob that he was his father. As far as I know, Bob never saw him again. Bob said his father had another family living in Sonora.

Bob remembered fondly the evenings when, as a small boy, he would choose among the three women whose bed to sleep in. His grandmother warned him that if he dropped their hands while walking on the Paseo de la Reforma, he would be stolen by gypsies, have his eyes gouged out, and be put out on the street to sell Chiclets. So he held on for dear life.

Bob’s predominant memories of childhood were riding his bicycle around the adjoining interior balconies of their apartment building, and craving sugary pastries from the

bakery down the street. When they went to visit his uncle’s house in Sonora, the women never allowed him to touch the earthen floor, so as a result, he never moved but stayed on his bed all day, making figures from Plasticine and drawings of his three mothers.

Bob had amazing dexterity. Sometimes in restaurants he would fashion animals or figures or make constructions out of bread dough or mashed potatoes. He threw knives with chilling expertise, usually in public after a few tequilas, which had its charm but made me a little nervous. But his friends seemed unfazed by it. He had an eclectic collection of knives, pistols, and various firearms. Bob was great on harmonica and enjoyed playing along with Van Morrison on

Astral Weeks.

At times he was dead serious, but he could be ludicrously funny. He had all the best parts of Dad and Jack but not the temper, or the women. Early on in our relationship, he amused me by walking fully clothed into a swimming pool at a fund-raiser at Paul Mazursky’s. I don’t think he even asked for a towel afterward. Bob was also pyrotechnically inclined and liked to mess around with gas and lard and flame, frying up a whole turkey sitting on a can of beer, New Orleans–style, at Christmastime.

He loved jazz. He was elegant and wise and devil-may-care. He smelled of mint soap and clay and fresh cigar ash. He liked to wear a uniform of crisp cotton trousers, a starched white shirt ironed by his devoted housekeeper, Dora, and black Nikes. When I came into the picture, Dora had been working for Bob since 1987. She had a round pretty face and a steady gaze. I think it took a while for her to like me. Bob had been married twice before and had a grown son, Steven, by his first wife, Joey.

It was quite surprising how alike his and Dad’s and Jack’s

experiences had been as kids: single male children raised like little pashas by doting, often suffocating women. Jack, whose grandmother curled his hair in the beauty parlor as his aunt and mother lied about their relationship to him, claiming instead to be his sisters; and my father, who was confined to his bedroom as a child and taught himself to draw and paint and invent stories. Perhaps it was a common thread that also made them so comfortable and attentive in the presence of women but particularly responsive to the opinions of men.

Bob’s mother, Adelina, was a Rosicrucian and a charismatic. He told me that she could move a glass across a table with sheer willpower, that she loved to sing and dance; she was, in his words, a ham. His uncle ran a radio station in Mexico City that played jazz. His aunt Mercedes had been the inspiration for the Mexican singer and songwriter Agustín Lara when he wrote “Maria Bonita” and “Solamente Una Vez.”

Bob had an unusual living space a block from the beach, comprising three trailer units that had once been joined together to form an outlet for Bank of America. His studio, a tall Victorian brick building, was next door on Windward Avenue, the gateway to Venice. When I first began staying over, we were awakened one night by the sound of someone walking on the roof above the sliding-glass doors that led to the bedroom. As I watched in silence, Bob slipped out of bed with the stealth of a puma, gripping a snub-nosed .45 between his fingers. As he pointed the gun aloft, I heard him say, “You’ve got exactly ten seconds to get down from there.” The guy was whimpering as Bob began the countdown. It was impressive.

Bob cooked me perfect breakfasts and took me salsa dancing. He owned two Rottweilers, Duke and Natasha; Minnie

made the mistake of considering Duke’s dinner one day, and he went for her. He didn’t hurt her, but she was scared. I was, too. After that, Bob rented an apartment for his dogs across the street; appropriately, it bore a mural with the words

ANIMAL HOUSE

above its windows.

I was always worried about Minnie’s diabetes, and I hoped that my assistant, Molly, would remember to give her insulin shots when I was away or working or staying at Bob’s. One evening Bob and I went to see

Schindler’s List

, and when we got back to my house, I couldn’t find Minnie. Eventually, after some panic on my part, we discovered that she had somehow gotten out of the back yard and was shivering on the first step of the swimming pool, waterlogged but mercifully still alive.

Soon Bob and I were seeing each other regularly. He often made the commute to my house, and sometimes the journey from the sea to the hills of Benedict Canyon felt endless. I decided to show Bob the farm. “Don’t dress up,” I told him. “It’s very rustic.”

On the appointed day in July, he appeared in a white ten-gallon hat with a mink hatband, ostrich cowboy boots, and a huge turquoise-inlaid belt. He looked like he’d walked straight off the set of

Dynasty.

I was momentarily horrified but determined not to show it. When our eyes met, he laughed. “It’s okay, don’t worry,” he reassured me. “It’s a joke.”

Bob was thin with long legs. Like Dad, he was born under the sign of Leo. He was a tenderfoot and, as it turned out, he hated to get his paws wet. Unaware of this phobia, in the heat of summer, I took Bob up into the Sequoia National Forest above my farm, where the river was fast-running, and the water flowed down fresh from the mountains, full of golden

and rainbow trout. Bob had borrowed some banana-yellow Bermuda shorts from Steven’s collection of surf-wear, and as we waded across the shallow water by the bank, over the slippery rocks, I laughed out loud at his incongruous appearance. Not until we were midway and entering the deeper water in the middle of the stream did I notice that his eyes were wide with fear. I could tell by the expression on his face that this was his idea of hell, like putting a cat in a bath. The rocks were very slippery and he was crouched over, visibly panicked.

When we reached the opposite bank of the river, he sank down to his knees in a cave and said, “That’s it, I’m staying here.” It took a good hour for me to convince him that he would not drown on the way back and that it would be a good thing to leave before dark, when the bears and rattlesnakes would come out.