Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (22 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

One promising new technology is to make new piers out of recycled plastics or composites (a composite is a plastic or other polymer combined with glass, carbon, or aramid fibers), which ought to be a much cheaper material than concrete and steel, as well as being more environmentally friendly. Most important, shipworms won't munch on plastic. Granted, plastics have a weaker load-bearing capacity than concrete or steel, necessitating closer-together pilings, and no one really knows how long they last underwater. But the time had come to test this intriguing solution. One such test occurred on the south side of Hunts Point, the Bronx: in the mid1990s, the Tiffany Street Pier was constructed almost entirely of “plastic lumber,” which came from millions of two-liter soda bottles. Less than a year after the recreational pier opened, to great fanfare, it was struck in a freak lightning storm and its deck incinerated. One might almost think

the Almighty had intervened with lightning bolts to protect His lowliest creature, the shipworm, from extinction.

So shipworms and New Yorkers continue to coexist, uneasily. They have much in common: “Each lives alone in a crowd,” Jeffreys says of the teredo, though he might be speaking equally of the Manhattanite; each is obsessed with finding a suitable pad or consoling cocoon; each adjusts readily to obstacles looming in its path, while remaining solitudinously, morosely driven; each has workaholic, if not bisexual, tendencies.

10 FROM 42ND STREET TO RIVERSIDE SOUTH

B

EYOND THE CONVENTION CENTER, ABOVE 42ND STREET WALKING NORTH, IS THAT WHOLE BOLLIXED-UP TRAFFIC JAM OF AN AREA, THE AIRCRAFT CARRIER

INTREPID

museum and the Passenger Terminal for ocean liners. The heyday of this area was when all the Queens docked side by side—the

Queen Mary

, the

Queen Elizabeth

, the

Normandie

, the

Ile de France—

and when Cole Porter wrote, in “I Happen to Like New York,” that he liked to “watch those liners booming in”; they came all that distance because they, too, “happen to like New York.” In those days, even Upper East Side snobs who said they never went over to the West Side amended that with “except to go to the French Line.”

Now these piers seem drab and inhospitable. If there is any glamour still attached to ocean liners, you would not be able to sense it from the

fortresslike vanilla concrete ramps designed for cars, not pedestrians. There are no sidewalks, period. I contemplate buying a ticket to the gunmetal gray

Intrepid

, but I've been on it, twice, and each time felt that the thrill of martial experience and historical sacrifice was eluding me. Instead, it seemed an ill-sorted collection of maritime junk. The glass box they've built in front to house a McDonald's doesn't help inspire feelings of nationalistic reverence. I may as well keep walking. It's supposed to be great walking along the waterfront, but around here I'm starting to feel lonely. Cut off. I'm not having a good time! I miss all the faces that would be rushing at me in the crowded streets. I'm starting to get that ominous sense of emptiness, the one that comes on me in other cities, where the dense urban web starts to thin out—like the warehouse district of Los Angeles, or the border between Houston's downtown and its ship channel—and suddenly there aren't enough buildings or color to support a walk for pleasure, and I'm thrown in on myself, that worm! that bluffer! that emotional disappointment to his friends and family, leaving them always feeling hungry, or judged. There'd better be something interesting looming up ahead, or I'll have to do a number on myself. That funny truck mounted on the roof of a one-story building, a species of folk art? No, nothing much there. The place where they make H&H bagels? So what? Hey, look at that weird sign on the World Yacht gate: dinner and brunch cruises. Whoever heard of a

brunch

cruise?

The problem with writing a walk down is that the details are infinite, therefore not worth pursuing. As the poet Louise Gluck said: “We have made of the infinite a topic. But there isn't, it turns out, much to say about it.”

At Pier 94, “The Unconvention Center,” they are shooting an episode of

Law & Order.

Lots of actors dressed as cops stand about tensely. An empty canvas-back chair reads: Jerry Orbach. The star is nowhere in sight. I remember seeing him recently at a bistro in TriBeCa, looking frail, sitting with a young admirer. After contemplating his memory, I'm thrown back on myself: you fraud, you dope, you don't know anything.

Ah, but maybe it's not my fault, maybe it's because there really isn't a continuous path for walkers along the riverfront. The promise is in the air, but the reality is decades away. So I'm trying to make a coherent experience out of something that isn't one yet. All these pathetic little bike paths

and dog runs that give out suddenly after three blocks. These makeshift “walkway” arrows that point you around a construction site, or the dan-ger?private property?keep out signs. If you would walk the waterfront, you have to do it in the spirit of a trespasser: follow the legal pedestrian route until it becomes ambiguous, or the sidewalk disappears, and you find yourself in no-man's-land, dodging eye contact with the occasional workman who might shoo you away, or the derelict who might importune you for a handout—perfectly fine, under ordinary circumstances, but it bothers you now since you feel so illegitimate yourself. In any case, I tell myself, it's not my fault, I'm not a bad person, there are objective, tangible

reasons

for my malaise.

NOTHING MUCH TO SAY about this mostly forlorn stretch of waterfront along the West Fifties, until I come to West 59th Street, where a marine transfer station is being reestablished to ship the city's garbage someplace else. The transfer station is graced with a wacky Greek temple portal, designed by Richard Dattner, and neon-lit by artist Steven Antonakos, that tries a touch too hard to be playful, but at least it tries. Across the way is the stately old Consolidated Edison/IRT powerhouse, whose distinguished architectural pedigree (McKim, Mead and White) may protect it from demolition.

At West 59th Street and the Hudson River, you may also enter the new waterfront park, Riverside South. This piece of land, stretching from here to 72nd Street, was until fairly recently the West Side Rail Yards of the New York Central. Cornelius Vanderbilt, the “Commodore,” had created that powerful railroad by merging several weaker lines in the nineteenth century. Not only did the New York Central offer passage north on both sides of the Hudson River, and westward following the Erie Canal route, it was the only railroad line actually to enter the island of Manhattan. The other lines, including New York Central's mighty competitor, the Pennsylvania Railroad, stopped short at the continental, New Jersey side of the Hudson River, and had to ferry passengers across, while loading freight onto barges pulled by tugboats.

It was New York Central's idea to split its Manhattan lines in two: one, the passenger line, would cross over eastward and terminate in Midtown,

at Grand Central Station; the other, devoted strictly to freight, would continue downtown along the West Side's perimeter, eventually concluding in St. John's Park Freight Terminal (which still exists), at Houston and Hudson Streets in Greenwich Village. In order to alert cars and pedestrians on Tenth Avenue of an approaching freight train, men on horseback would precede the train, galloping along the tracks.

One reason the practice was discontinued was that the trains occasionally struck an inattentive pedestrian or car driver, causing the route to be nicknamed “Death Avenue.” The freight delivery system that replaced the open tracks was a viaduct built between the West 33rd Street train yards and St. John's Park Terminal, passing wondrously through and between buildings, known as the High Line. (There is now a worthwhile effort to preserve it from demolition and turn it into an elevated park.)

Even after the city ordered the removal of all railroad tracks at grade below 59th Street, the West Side Rail Yards continued in full operation. It was one of three major yards along the West Side, the other two being at West 33rd Street and West 130th Street (Manhattanville). The New York Central built all three between 1877 and 1882, shortly after it had erected its first version of Grand Central Station on 42nd Street. The West Side Rail Yards contained a roundhouse, a grain elevator, stockyards, sections to make up trains, an engine service terminal, and eight piers for barges and ships. The piers testified to the importance of the Rail Yards as a marine-rail transfer zone. Although the New York Central's monopoly of rail access into Manhattan at first gave it an enormous advantage in securing freight, the company found that rail freight was still costlier than barge (since water is cheaper to maintain than railroad track), and that its freight lines would also be difficult to expand in the routes available. Consequently, the New York Central began also employing a lighterage system between its Weehawken, New Jersey, terminal and the West Sixties rail yards.

“Lighterage” refers to the movement of freight within a harbor by barge. “Car floats” more specifically designate railroad cars loaded onto a barge. So prevalent became this means of freight transport that an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 railroad cars floated every day across New York Harbor in the first half of the twentieth century. It is mind-boggling to think of all those flat-bottomed vessels piled high (one barge could hold

eight or more carloads of freight), crossing very near each other on the crowded seas. In their heyday, the barges were almost as synonymous with New York's iconography as its skyscrapers.

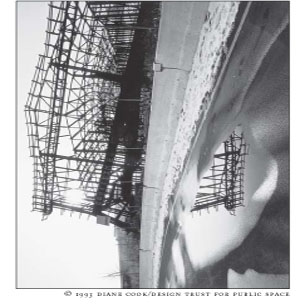

The most complicated piece of equipment in the Rail Yards was probably the West 69th Street transfer bridge, built in 1911 and engineered to load 1,000 tons on a vessel in ten to fifteen minutes. A transfer bridge (sometimes called a “float bridge”) was a technology perfected during the turn of the twentieth century; it could roll a railroad car from a train onto a barge, for transport across the river, without having to unload it. The hard part was that the car floats listed from one side to another when being loaded; the transfer bridge had to be designed to absorb these tortional motions and keep the cargo from falling in the river. The solution, invented by the engineer James B. French, was a “contained-apron” type (don't ask me to explain it). So successful was French's West 69th Street bridge that afterward “all

new

suspended bridges built at the Port (twentyone of them) were built to his design,” concluded Thomas R. Flagg, the world's authority on New York Harbor transfer bridges.

The West Side Rail Yards were located at the bottom of a sloping pit, separated from any residential neighborhood, which may be why they survived longer than similar waterfront facilities in Manhattan. The West Side Rail Yards were still on the scene when the New York Central merged with the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1968, and still on the scene when that amalgam went bankrupt two years later, in 1970, the casualty of public highways, air travel, and containerization. Pieces of the extinct Penn Central's routes were absorbed by Amtrak and local commuter systems; but the once-dominant water belt line, which had so capably moved freight on the backs of barges, had all but disappeared. As Carl Condit put it so well in his book

The Port of New York:

“One may plausibly debate the question whether the later city of vehicular bridges and tunnels and distant airports is an urbanistic and ecological improvement over the earlier city of railroads, lighters, carfloats, and ferries.”

During the 1970s, when I lived on West 71st Street, I would frequently wander west a few blocks to where the street dead-ended in an overlook, and gaze down at the idled train yards. It gave me a mysterious feeling, looking north to the landscaped Riverside Park, which began at 72nd Street, and then south, a few hundred feet away, to this scruffy, sloping terrain

and the unkempt, deserted tracks below. You knew even then, at the height of the city's fiscal crisis, that it couldn't remain that way much longer. Someone would begin to buy up the parcels and turn it into a huge, Upper West Side, Lincoln Center–oriented development. And that is precisely what Donald J. Trump did. This high-living real estate developer, whose fame rivaled that of rock stars, whose glowing good health, ego, money, and appetite for well-endowed blondes fed the tabloids' gossip pages, who wrote (or had ghost-written for him) best-sellers about how good it felt to have it all, to pull off successful deals and cut through the bureaucratic logjams of building anything in New York—this self-confident scalawag whose name was put forward at one time as a Republican candidate for president, and who represented, to a resentful faction of Democrats, Mammon himself, in 1983 purchased for $95 million, with the help of his mostly silent Chinese partners, these seventy-six acres of prime waterfront property, the then-largest undeveloped site left on Manhattan, on which he proposed to build the tallest tower on earth, 150 stories, plus the new NBC television studios, 7,600 units of housing, and a major shopping mall, all to be named—Trump City, or, on more modest days, Television City.