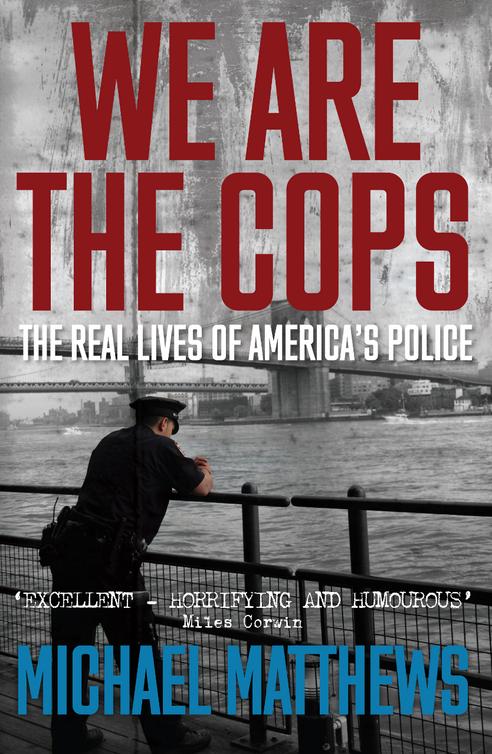

We Are the Cops

Authors: Michael Matthews

MICHAEL MATTHEWS

London

This book is dedicated to law enforcement officers, past, present and future and to those who have given their lives or who may never recover from their injuries.

‘We’re the police. We’re not fucking social workers.’

C

razy stuff happens in the States, and more often than not it’s the cops who end up dealing with it. As a result, policing in America stands alone, because of its environment (natural and man-made), its attitudes and approach, its extremes, its dangers, its excitement and its contrasts. Here is a group – a family – of men and women who are to be admired and at times even envied. These are people who face and do the extraordinary, whose job it is to run towards danger for the sake of other people.

This book is intended to be a window into their lives, a way of showing the world what it is really like to be a cop in the US by using the words of the people who know it best – the cops themselves. The voices in this book are all different, from different cities, states and counties, male and female, rookies and veterans. But they are also all the same, because they are all cops.

There are close to eight hundred thousand law enforcement

officers in the United States of America which, considering the population of the country, actually isn’t that many (the UK has more per capita) and, leaving out Federal Agencies, they are generally spread over three different types of agency: state troopers, county sheriffs and local police departments. All enforce the law in one way or another, but it is not that straightforward. Each is distinct and even within their own kind there are numerous variations and differences. So although this might not be entirely correct in all cases, put most simply, this is how I see them: State Troopers (known in some states as State Police, Highway Patrol or Department of Public Safety) are paid for by the state and have jurisdiction over the entire state. Each state is then split into a number of counties (although Alaska doesn’t have any) and each county has its sheriff’s department (although Connecticut has state marshals instead), who have law enforcement responsibility throughout their own county. Then there are the local police departments that are generally paid for by the towns and cities they police. Some of these local police departments are actually ‘Public Safety Departments’, where the officers are trained and act as both police and firefighters. It’s a good way of keeping down costs, I guess.

But not all towns and cities have their own police department because if they want one, they have to pay for it themselves, and in these circumstances the sheriffs and/or the troopers serve them. For example, if Los Angeles decided that it no longer wanted or could no longer afford a police department, the LAPD wouldn’t exist and so the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, (the

city and the county have the same name in this instance), would take over the full time policing of the city.

But a city would never let its police department go, right? Wrong. This does happen. I myself have seen it first hand in Michigan, where the Highland Park Police Department was dissolved in 2001 because the city could no longer afford them. Shortly afterwards, I was shown around this poor, rundown city by the handful of county sheriffs who were tasked with keeping some kind of law and order in a city where the police had simply been there one day then gone the next. The abandoned police station and police cars had been vandalized and destroyed in what looked like an orgy of anarchy. Fortunately the department has since been re-established.

There are a staggering amount of different law enforcement agencies in America, close to 18,000, including over 12,000 police departments (the NYPD being the largest with 34,500 officers); literally thousands of separate agencies and departments – state, county, city, university and school departments, federal agencies and special districts such as airport, harbour and transit departments. Although there are other things to take into consideration such as size and population (the UK population is roughly five times smaller than the US – 64 million compared to 318 million), by comparison, the UK has 51. I questioned why some smaller departments didn’t amalgamate (I know of a department where the Chief of Police is in charge of himself) and a cop in New England told me that the local communities had no appetite for it. They liked having their own, dedicated departments.

Like a gated community with private security, I thought. But the amount of departments and agencies – along with the variations within them – can be mind-boggling.

Despite all this, the model for ‘modern’ policing in the US came from Great Britain, Sir Robert Peel and the London Metropolitan Police. But policing in America goes back further than Peel and although there were previous ‘watches’ and patrols, the first city to employ ‘police’ was Philadelphia in 1751. And the first recorded officer death was as far back as 1791, when Constable Darius Quimly of the Albany County Constables Office in New York was shot dead during an arrest. Over two hundred years later, the wall at the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington DC now contains nearly 20,000 names.

Since the turn of the twentieth century, the number of officer deaths per year has almost always been in triple figures. The figures vary, depending on the recording methods, but according to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial, the 1970s were a particularly deadly decade with 2,301 recorded deaths – an average of 230 a year. 1974, the year of my birth, was the decade’s most lethal, with 280 officers killed, which was just shy of the 293 officer deaths recorded for 1930. Elsewhere it is recorded as 313 officers but either way, it is the highest ever year. The 1920s were even worse than the 1970s, with an average of 235 officers killed a year and a total of 2,355. I find these figures shocking. But then the figures for all years are always astounding, even though they can fluctuate wildly. 106 deaths were recorded for 2013 – the lowest figure since 1944 – and although it’s down from the 123 that

were recorded for 2012, it is still tragically and shockingly high.

The causes of officer deaths range from stabbings to vehicle accidents. Many are recorded as ‘gunfire’. Four of the officers who died in 2012 were New York Police Department officers who finally succumbed to the effects of 9/11 and the toxins they breathed in during the rescue and recovery operation. On other years that number has been higher. It is obviously a dangerous job and police officers also kill hundreds of people a year in the US, in what is classed as ‘justifiable homicides’; The difference being that one set of people are legally in the right and the other are in the wrong.

I remember being acutely aware of the dangers of being a cop in the US when I was growing up and watching American cop shows such as TJ Hooker, CHiPS, Hill Street Blues and movies like Lethal Weapon, Turner and Hooch, Stakeout and even Smokey and the Bandit. However, I was convinced that American cops were the coolest guys in the world, all ass-kickin’, cigar-chomping, gun-toting men of action with endless attitude and a bottomless collection of sharp wisecracks. For me, an English kid in the genteel London suburbs, they couldn’t have been more different to our own British Bobbies. Nowhere did policing seem so extreme and as much fun as it did in America.

A few years on, having finally reached the required age, I phoned the American Embassy in London in a state of great excitement, and asked about joining the NYPD. It had to be the NYPD because to my TV-educated teenage mind they were the

craziest of the bunch (later I would learn for myself that really was true).

‘Hi,’ I said to the female operator, my voice full of enthusiasm. ‘I want to join the NYPD.’ For some reason I half-expected her to hand me a gun and a badge through the telephone receiver.

‘Join the what?’ she said.

‘The New York Police Department.’

‘You want to be a cop?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘In America.’

‘Are you American?’

‘No.’

She hung up.

As much as I loved her show of real American attitude, I was deeply disappointed. I immediately resolved to make a life for myself which was as close as I could get to the NYPD: I became a British cop, or rather, a British policeman (I quickly learned that using the term ‘cop’ in the UK makes you seem ridiculous).

Over the next ten years or so, my obsession with the American police grew, and eventually I began travelling to the United States to find out more. I quickly learned about the ‘ride-along’ programs, which allow private citizens – usually with an interest in joining the police – to experience the life of a cop by going out on patrol with an officer in their local town. Despite not even being American, and often not even being understood, I was always allowed to ride. And the experience was everything I hoped for and dreamed of, because it really was like being in a US cop show. Car chases, foot chases, drawn guns, fist-fights,

drugs, arrests, attitude – from both the cops and the perps – and even ‘dip’, which I learnt was a way of taking tobacco by placing a wad of damp black stuff under your lip, sucking it and then pretty much making yourself sick.

As the years went on, I travelled to the States more and more, always hooking up with officers right across the country, going on ride-alongs and learning what life was like for the men and women who work in law enforcement. My fascination with their work and their lives was obvious, and they would often tell me about their experiences. That is where the idea for this book came from – the officers themselves.

Over the years that I have been patrolling and meeting with American officers, I have laughed so hard that I have hurt myself, cried for and cried with officers and the people they come into contact with. I have rolled around on the ground with violent suspects, assisted in arrests, chased criminals and helped those in need. I have been more scared than I had ever been before or have felt since, and have feared for my life on more than one occasion. I have felt extreme happiness, hope and joy but also reached rock-bottom despair, distress and terror – experiences and emotions that cops feel and go through every single day.

At the end of days like that, cops get a pay cheque and a pension – if they are lucky. As you will read, some will not make it that far. Many will come away scarred for life physically or mentally, or both. Some will also get to take memories and experiences away with them that most people could not dream up in the wildest parts of their imagination. Many of these are shared

in the following pages.

Other books of this type have been written before, but they often related to a single officer or focused on small geographical areas, perhaps just one force. I wanted to put a book together that gave the reader a wider view of policing in America. Although there is much that may be similar in the work of a cop in New York and a trooper in, say, Alaska, there are many differences. For one, you don’t get moose in Times Square.

I wanted this book to be different, to be more than just funny tales or stories of gunfights, although they would be important parts. I also wanted to know what made cops tick. I wanted to get under the uniform, out of the handcuffs and find out how they really felt about their job, their colleagues, the politics and the public. I wanted to know what a cop really thinks about and how they feel, to get a broad and deep understanding of modern police in America today. The project proved to be exhausting, but man, what an adventure.

The finished book is not separated into departments or individual officers. Instead it is arranged under specific subject headings with officers’ tales all mixed together, and starts where all police officers careers start – The Rookie. I have then attempted to roughly follow the career path of some, but not all, police officers: working on patrol, moving into specialist departments and then, perhaps, if the officer was career minded in that way, moving into detective divisions such as Homicide and Vice. There are some stories that would easily fit into more than one category but I have placed these in the chapters where I felt they were best

suited. The job, as you will read, can and does take its toll and the chapters Officer Down and The Negatives show this only too well. Emotionally, they were the toughest to write.

Towards the end of the book is one officer’s experiences from 9/11, an incident like no other and an attack that took the lives of many thousands of people including sixty police officers. Firefighters had a reason to climb those towers (a staggering 343 of them were killed, including a chaplain and two paramedics). But police officers, who were not carrying breathing apparatus, hoses or fire resistant clothing, just did what cops do; they went there to do whatever they could to help, no matter what that might turn out to be. Heroes, every one of them. Cigar-chomping heroes with attitude, I like to think.

So here it is; America’s police, telling it like it is.