We Two: Victoria and Albert (58 page)

Read We Two: Victoria and Albert Online

Authors: Gillian Gill

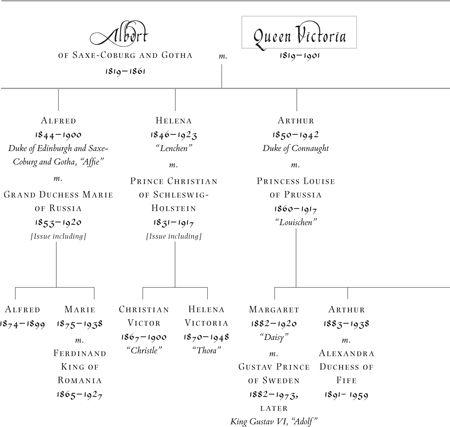

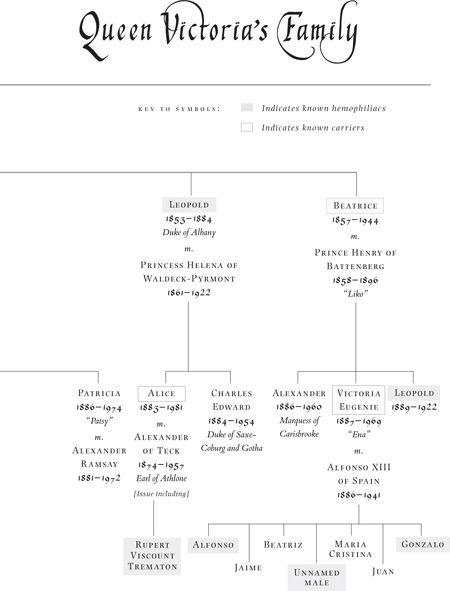

Nicholas and Alix went into marriage wholly ignorant of the “hereditary tendency to fatal bleedings” in her family. Young and in love, they might have married even had they known, willing to take risks that still had not been calculated. As the medical historians D. M. and W.T.W. Potts note: “The failure of the tsar’s family to appreciate the genetic risks was not due to ignorance in Russian scientific circles. More likely it was due to the isolation of the royal family from the intellectual life of the country and the scientific ignorance of the narrow circle of aristocrats and politicians with whom they associated.” The Saxe-Coburg policy of secrecy and willed ignorance had been all too successful.

A few years after the wedding of Alix and Nicholas, medical authorities in Spain did point out to their king that Ena of Battenburg, the beautiful, healthy, young English princess he wished to marry had two hemophiliac brothers. Alfonso XIII trusted his eyes, not his doctors, and married Ena— with dynastic results that only just fell short of the Russian tragedy. One wishes that Alix and Ena, both favorite granddaughters of Queen Victoria, had been given some idea of what they were taking on when they married kings of tottering dynasties desperate for healthy male heirs. As their first cousin Marie, Queen of Romania, explained in her memoirs, Queen Victoria’s daughters and granddaughters were “kept in glorious … but dangerous, and almost cruel, ignorance of realities.” Their upbringing was based on “illusions and a completely false conception of life.”

By the early twentieth century, the Saxe-Coburg family was the most famous case study of hemophilia in the history of medicine. Hemophilia had become known as the royal disease.

…

F LEOPOLD’S BIRTH IN 1853 WAS A SEVERE SETBACK TO QUEEN VICTORIA’S

F LEOPOLD’S BIRTH IN 1853 WAS A SEVERE SETBACK TO QUEEN VICTORIA’S

health and morale, by 1854 she had bounced back. This was as well, as the nation was at war with Russia, her workload was heavier, and she was again on the public stage. Her zest for life was on full display in 1855, when the royal family of Great Britain and the imperial family of France exchanged visits and, rather improbably, became bosom friends.

Great Britain and France were allies during the Crimean War, with their armies fighting on the plains below Sebastopol. The new ruler of France, Napoleon III, was anxious to profit personally from the English alliance. Shunned as an interloper by continental monarchs, the emperor saw Queen Victoria as his best hope for sponsorship in the royal club. Every court in Europe now knew that Prince Albert held the key to Buckingham Palace and that the only way to get close to the Queen was through him. Therefore, as an opening move, the emperor invited Prince Albert to come to Boulogne in August 1854 to spend some days reviewing the French troops and conferring with military leaders.

Napoleon III was not the kind of man Prince Albert habitually cared to cultivate. He was a nephew of the great Napoleon Bonaparte, whose ravaging armies were still recalled with horror in little German states like Albert’s Coburg. He was a supreme political opportunist and had touches of the mountebank, the roué, even the opium eater. In smooth charm he was not unlike Benjamin Disraeli, a rising political star in Great Britain whom Prince Albert could not abide. However, flattered to be treated as an expert in military matters, Prince Albert agreed to come to Boulogne. As a lengthy memorandum by the prince himself testifies, he and Napoleon III had

hours of weighty conversation on political issues and personalities. When Napoleon III asked for a state visit to England, Prince Albert said he would ask his wife, which the emperor correctly interpreted to mean yes.

Prime Minister Lord Palmerston and Foreign Secretary Lord Clarendon were rather surprised when the Queen agreed to receive the French emperor and empress at Windsor. Only ten years earlier, King Louis Philippe had enjoyed a magnificent state visit during which he received the Order of the Garter and was welcomed into the bosom of the English royal family as a beloved uncle. To the dismay of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the 1848 revolution, in which the then Prince Louis Bonaparte had played a principal role, toppled Louis Philippe from his throne, and the whole Orléans clan went into exile in Great Britain. By 1855 Louis Philippe was dead, but his children let out a furious cry of lèse-majesté when they learned of an impending state visit to London from their mortal enemies, the usurping Bonapartes.

Even Victoria was a little surprised to find herself preparing for the imperial couple’s visit. She had the state guest apartment at Windsor redecorated in the violet satin and gold eagles she favored, ordered her own gold toilet set to be put out for the empress, and tactfully requested that the Waterloo Room should be referred to for this occasion as the Picture Gallery. She felt virtuous to be putting aside personal feelings for the national good, and for once was deaf to the views of her extended family. Full of martial zeal and policy initiatives, Victoria was bent on using her personal influence to consolidate the entente with France, smooth over the often contentious negotiations between the allies on the battlefield, and restrain the emperor’s impetuous instincts.

She also had a nervous curiosity to meet the man in person. She was now accustomed to receiving guests from abroad and could rely on the smooth precision of Albert’s domestic management, but most of her house-guests were German family members. Louis Bonaparte and his Spanish wife, in contrast, were an unknown quantity. They were exotic, even louche, the kind of people Albert made sure she never met. The prospect of spending days in their company made Victoria’s heart pound.

Charles Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (1808–1873) was one of the most fascinating men of his generation and a politician of the first rank. During the reign of his emperor uncle, he lived for part of his youth in Augsburg, retaining traces of a German accent in French. After the final defeat of the Emperor Napoleon I’s army at the battle of Waterloo in 1815, Louis led the life of an outlaw, a prisoner, and an exile, returning periodically to France to try to incite a revolt against the restored Bourbon monarchy. For a number

of years, he lived on his wits in England, where he learned excellent if accented English. Force of will and an invincible sense of destiny brought him back into French politics in 1848, when he became the president of the new French republic. Three years later, he suspended the constitution, organized a plebiscite, and declared himself Napoleon III, emperor of the French.

The new emperor was a small, skinny man with a large head, an extraordinary mustache, and a libido to match. He had great charisma and was irresistible to women. In 1853, having failed in his quest for a royal bride, Napoleon sent shock waves through Parisian high society by choosing to marry a Spanish woman at his court, Eugenie de Montijo, who, remarkably, had resisted his advances. Eugenie was acknowledged to be one of the most beautiful women in Europe, but she was in her late twenties and her name had been linked to several men. She was the kind of woman a petty German ruler like Albert’s brother might take as a mistress or marry morganatically but certainly not choose as the mother of a new dynasty.

During the week that the Bonapartes spent with the Saxe-Coburgs at Windsor, the emperor flirted expertly with the Queen, and Victoria fell under his spell. At the very first dinner, Louis enchanted his hostess by recounting how he had once stood in the crowd in Green Park to watch her drive by on her way to her first prorogation of parliament. In 1840 he had paid forty pounds he could ill afford for a box at the opera from which he could gaze at her and her new husband. At the grand ball in the “Picture Gallery,” the Queen and the emperor, both excellent dancers and well matched in height, danced a quadrille to the admiration of all. “How strange to think,” Victoria confided in her diary, “that I, the granddaughter of George III, should dance with the Emperor Napoleon, nephew of England’s greatest enemy, now my nearest and most intimate ally in the

Waterloo Room

, and this ally only six years ago living in this country, an exile, poor and unthought of.” As Foreign Secretary Lord Clarendon remarked, after observing the pair on a number of occasions, Napoleon’s “lovemaking was of a character to flatter [the Queen’s] vanity without alarming her virtue.”

One day of the imperial visit was perforce spent at Albert’s Crystal Palace. On the way to and from Buckingham Palace and especially walking down the main nave of the exhibition hall, the royal party was mobbed by enthusiastic, cheering crowds. This was a security nightmare, as Napoleon III had political enemies of many persuasions and was under constant threat of assassination. Acutely aware of the danger, Victoria took her guest’s arm and pressed close. “I felt that I was possibly a protection for him,” she confided to her journal. “All thoughts of nervousness for myself were past. I thought only of him: and so it is, Albert says, when one forgets

oneself, one loses this great and foolish nervousness.” Victoria herself survived seven assassination attempts, but she reserved her “nervousness” for childbirth.

Two councils of war were held during the imperial visit to England, the first composed exclusively of men. Prince Albert joined in the discussions and was delighted to be chosen to take notes and draw up the memoranda. Eugenie and Victoria waited outside, and finally, at Eugenie’s prompting, Victoria dared to go in to ask the men if they intended to eat lunch. The answer was a polite yes, but they did not, in fact, emerge until it was time for the emperor to dress for the Garter ceremony. Victoria and Eugenie lunched alone. However, at the final council of war, “the presence of the Queen was, of course, indispensable,” as Victoria notes with some pride in her biography of her husband. Her signature was needed on the documents her husband was busily drafting.

While the men talked, Victoria and Eugenie were thrown into each other’s company, and they hit it off tremendously. Victoria looked with pleasure on Eugenie’s beauty, sympathized with her nervousness on state occasions, and appreciated the warmth of her nature. The two women would be friends for the rest of their long lives. Albert too melted before the empress’s charm and praised the elegance of her toilettes. “Altogether I am delighted,” Victoria confided to her diary, “to see how much Albert likes and admires her, as it is so seldom I see him do so with any woman.”