We Two: Victoria and Albert (6 page)

Read We Two: Victoria and Albert Online

Authors: Gillian Gill

NOTE

:

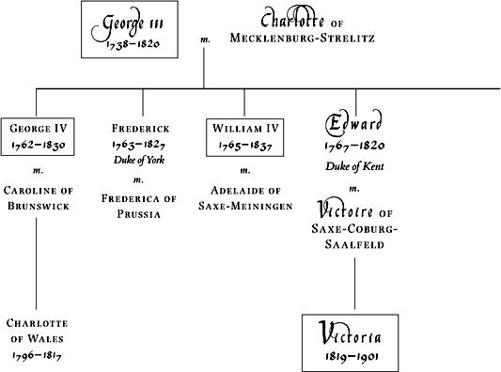

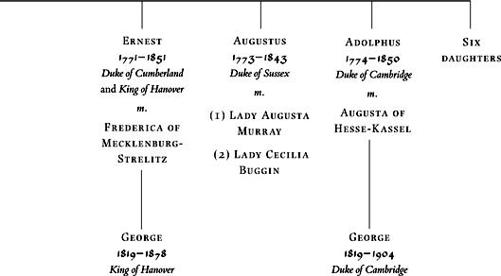

Charlotte, Augusta, Elizabeth, Sophia, Amelia, and Mary, the six daughters of George III, were of no relevance to the royal succession, which gives precedence and inheritance rights to males, regardless of birth order

.

The royal dukes’ combination of egotism, vulgarity, idleness, promiscuity, and fiscal improvidence bred hatred and resentment on every level of English society. Even today it is staggering to consider the size of the debt they piled up. George, the Prince of Wales, as befitted the eldest son with the largest income, was the most extravagant. At the age of twenty-one, already 30,000 pounds in debt, George was given an annual income of 50,000 pounds to add to his existing 12,000 pounds a year, plus a flat sum of 60,000. In 1786 he was forty-four and now in debt to the tune of 269,878 pounds, 6 shillings, and 7 pence farthing. Between 1787 and 1796, the Prince of Wales ran up debts of 630,000 pounds—approximately 40 million in American dollars. When he agreed to get married, parliament paid off his debts and raised his income, but his spending continued unabated during his regency.

With Princess Charlotte dead, one of the seven royal princes would have to produce a legitimate child who could inherit the throne after the demise of one or more of his or her uncles. Of the seven brothers, three (George, Frederick, and Augustus, numbers one, two, and six, respectively) were extreme long shots in the dynastic steeplechase, since all three were, in one way or another, married but without legitimate offspring as legitimacy was defined by the Royal Marriages Act. Should any of the senior royal princes lose his wife and remarry, the handicapping of the race to an heir would, of course, change overnight.

After his wife Queen Caroline’s death in 1826, George IV, at fifty-five, at first was full of plans to find himself a new wife, but, in fact, he did nothing. He was too ill, too immobile, too full of opium and brandy, and too completely under the thumb of his mistress, Lady Conyngham. He died in 1830.

Odds were also against the next brother, Frederick, Duke of York. When Frederick was a young man, his older brother George, then Prince of Wales, asked him to take on the tedious job of supplying heirs to the throne. Happy to oblige his favorite brother and not, incidentally, to ingratiate himself with their father the King and with parliament, Frederick speedily contracted

to marry Frederica, second daughter of the King of Prussia, a not unattractive sixteen-year-old he had once seen in Berlin. Unfortunately the Yorks, Fred and Freda, like the Waleses, George and Caroline, separated within a year of marriage and failed to produce even one child. Given the diplomatic susceptibilities of Prussia, divorce for the Yorks was impossible. In 1820 Frederica, Duchess of York, died, and George once again begged Fred to bite the dynastic bullet and marry for an heir; but Fred, enamored of the Duchess of Rutland, could not be tempted. The Duke of York died, virtually penniless, in 1827.

Augustus, Duke of Sussex, the sixth son of George III, had to be eliminated at the outset, since he too was married (sort of) and had no legitimate offspring (as defined by the Royal Marriages Act).

Thus there were four royal dukes in a position to supply an heir to the throne: Clarence, Kent, Cumberland, and Cambridge, by order of birth and precedence.

William, Duke of Clarence, was third in the fraternal hierarchy, and thus the front-runner with numbers one and two scratched. He was as improvident and fond of luxury as his older brothers, on a much smaller income. Unlike them, he was a proven sire, boasting ten boisterous children by his charming actress mistress, Mrs. Dorothy Jordan. These children were known as the FitzClarences, “Fitz” being a standard marker for illegitimacy in English genealogy. The FitzClarences were accepted at court, though their mother, of course, was not, and all ten would ultimately, by royal patronage or marriage, become members of the English aristocracy. However, Clarence’s debts mounted inexorably, and in 1811 he decided, with regret but without warning, to find himself a wealthy and amiable young wife.

For six years his efforts at courtship went for nothing. Miss Tilney Long, Miss Elphinstone, and Lady Berkeley decided they could not afford the Duke of Clarence. Miss Wykeham accepted the Duke’s proposal of marriage, but, since she was, like the other four, ineligible under the Royal Marriages Act, the prince regent refused to accept her as a sister-in-law. The tsar’s sister found the fat, bumbling, vulgar, pineapple-headed Clarence too ridiculous to even consider as a husband.

But when his niece Charlotte died, Clarence knew what he needed: a German princess of child-bearing age who would satisfy the requirements of the Royal Marriages Act and get him a raise in his parliamentary allowance. With the help of his brother the Duke of Cambridge, viceroy in Hanover, Clarence settled, sight unseen, on Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen. She was a rather sickly, unattractive young woman of twenty-five, as poor as a church mouse. She was also intelligent, cultured, and pious, but these

assets rather counted against her with a fiancé who had gone to sea as a midshipman at fourteen.

The marriage between William and Adelaide proved to be a happy one. Trained by Dorothy Jordan, William was a profoundly uxorious creature, and Adelaide made him feel comfortable. But she was delicate, and though she conceived again and again, only one child, named Elizabeth, lived more than a few days.

The fifth royal brother, Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, was the most energetic, the most intelligent, and the most ambitious of the seven. He was also perhaps the most feared and hated man in England. Cumberland was widely believed to have murdered a valet who had been his homosexual partner and to have sired a bastard with his sister Sophia. These accusations were probably unfounded, but Cumberland was indubitably a violent, rapacious, unfeeling man. He was also head of the ultraconservative wing of the Tory Party and used his influence over his brother George IV to block political and economic reform.

Cumberland, though only brother number five, took an early lead over the other three, since they were bachelors when Charlotte died, and he had providentially thought to acquire a German princess wife in 1815. Cumberland proved his indifference to public opinion and lack of family feeling by choosing to marry Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. She was once engaged to Cumberland’s younger brother the Duke of Cambridge but then eloped with the Prince of Solms, a German nonentity whom she was later suspected of murdering. Queen Charlotte, the wife of George III, also born a princess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, was Frederica Cumberland’s aunt but refused to receive her at court. Nonetheless, the Cumberland marriage satisfied all the provisions of the Royal Marriages Act, and any child born to the couple would be eligible to inherit the English throne. The prospect that the bogeyman Cumberland might eventually come to the throne of England after his brothers—or at least, with his notorious wife, provide the new dynastic line—was viewed with extreme alarm by both statesmen and ordinary citizens in England.

The Duke of Cambridge, the seventh and last brother, was not about to be outdone in the dynastic stakes by his loathed elder brother, Cumberland, and his treacherous ex-fiancée, Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Cambridge was comparatively young, he had led a sober life, and, as viceroy in Hanover, he had the list of available German princesses at his fingertips. A mere two weeks after his niece Charlotte’s death, Cambridge was standing at the altar with twenty-year-old Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel. In

March 1819, in Hanover, the Duchess of Cambridge went into labor with her first child, the first of the post-Charlotte generation.

The Duke of Clarence, Cambridge’s older brother, was also living in Hanover at this time, in an effort to save money, since parliament had proved stingy. Clarence’s wife, Adelaide, was heavily pregnant with her first child. Hearing that his sister-in-law Cambridge was in labor, Clarence rushed over to the viceregal palace with two friends and sealed off all the doors leading to the birthing room. Just as Privy Councillors were supposed to attend royal accouchements in England, the men watched from an anteroom as the labor proceeded, ensuring that there could be no substitution of babies. As soon as the Duchess of Cambridge delivered her child, Clarence rushed in to “determine its sex by actual inspection.” Couriers then rode off to England to announce that George III at last had a legitimate grandson, to be called—what else?—George.

On March 27, in Hanover, a daughter was born to the Duke and Duchess of Clarence, but she died within hours of birth.

Two months later, on May 29, the Duchess of Cumberland in Berlin produced a son, and he too was named George. Since Cumberland was the fifth duke and Cambridge only the seventh, little George Cumberland at birth took a position in the line of succession ahead of little George Cambridge. The paternal aunties, daughters of George III, were overjoyed by the sudden arrival of not one but two healthy male nephews, either one of whom seemed, surely, destined to follow his uncle King George IV as King George V.

But it was not to be. For on May 24, a healthy daughter was born in Kensington Palace to the Duke and Duchess of Kent. Since Kent was the fourth brother, and Cumberland and Cambridge were the fifth and seventh, respectively, the Kent girl was fifth in line of succession to the throne and took precedence over her male cousins. Presuming that her uncles the prince regent, the Duke of York, and the Duke of Clarence produced no child, male or female, and that her own parents did not go on to have a son, this baby girl would one day be queen regnant in England.

The Kent baby would come to be known as Victoria.

THE DUKE OF KENT

was royal brother number four, and when Princess Charlotte died, he too was an aging bachelor. For twenty-seven years, first in Gibraltar and Canada and then in England after he was forced out of his army command, the duke lived in great content and considerable luxury in

the company of his French mistress, known to the world as Madame Saint Laurent. But by 1816, Kent’s credit in England had run dry, forcing him to live in Brussels and give over three-quarters of his parliamentary income to trustees in England for scheduled repayment of debt. Kent decided he must give up his mistress. He began looking for a wife who would satisfy the provisions of the Royal Marriages Act, anticipating six thousand extra parliamentary pounds a year as a married man.