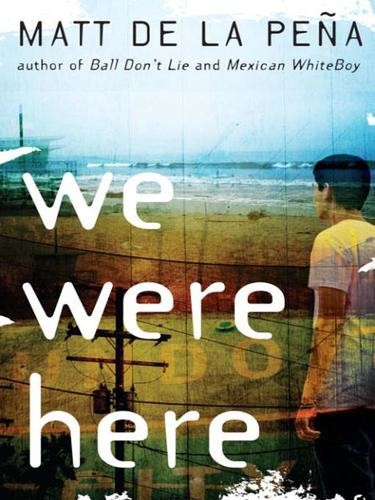

We Were Here

Authors: Matt de la Pena

ALSO BY MATT DE LA PEÑA

Ball Don’t Lie

Mexican WhiteBoy

TO SPENCER FIGUEROA

(My bad about all those times I dunked over you

when we were kids.)

One changes so much

from moment to moment

that when one hugs

oneself against the chill

air at the inception of spring, at night

,

knees drawn to chin

,

he finds himself in the arms

of a total stranger

,

the arms of one he might move

away from on the dark playground

.

—Denis Johnson, “From a Berkeley Notebook”

May 13

Here’s the thing: I was probably gonna write a book when I got older anyways. About what it’s like growing up on the levee in Stockton, where every other person you meet has missing teeth or is leaning against a liquor store wall begging for change to buy beer. Or maybe it’d be about my dad dying in the stupid war and how at the funeral they gave my mom some cheap medal and a folded flag and shot a bunch of rifles at the clouds. Or maybe the book would just be something about me and my brother, Diego. How we hang mostly by ourselves, pulling corroded-looking fish out of the murky levee water and throwing them back. How sometimes when Moms falls asleep in front of the TV we’ll sneak out of the apartment and walk around the neighborhood, looking into other people’s windows, watching them sleep.

That’s the weirdest thing, by the way. That every person you come across lays down in a bed, under the covers, and closes their eyes at night. Cops, teachers, parents, hot girls, pro ballers, everybody. For some reason it makes people seem so much less real when I look at them.

Anyways, at first I was worried standing there next to the hunchback old man they gave me for a lawyer, both of us waiting for the judge to make his verdict. I thought maybe they’d put me away for a grip of years because of what I did. But then I thought real hard about it. I squinted my eyes and concentrated with my whole mind. That’s something you don’t know about me. I can sometimes make stuff happen just by thinking about it. I try not to do it too much because my head mostly gets stuck on bad stuff, but this time something good actually happened: the judge only gave me a year in a group home. Said I had to write in a journal so some counselor could try to figure out how I think. Dude didn’t

know I was probably gonna write a book anyways. Or that it’s hard as hell bein’ at home these days, after what happened. So when he gave out my sentence it was almost like he didn’t give me a sentence at all.

I told my moms the same thing when we were walking out of the courtroom together. I said, “Yo, Ma, this isn’t so bad, right? I thought those people would lock me up and throw away the key.”

She didn’t say anything back, though. Didn’t look at me either. Matter of fact, she didn’t look at me all the way up till the day she had to drive me to Juvenile Hall, drop me off at the gate, where two big beefy white guards were waiting to escort me into the building. And even then she just barely glanced at me for a split second. And we didn’t hug or anything. Her face seemed plain, like it would on any other day. I tried to look at her real good as we stood there. I knew I wasn’t gonna see her for a while. Her skin was so much whiter than mine and her eyes were big and blue. And she was wearing the fake diamond earrings she always wears that sparkle when the sun hits ’em at a certain angle. Her blond hair all pulled back in a ponytail.

For some reason it hit me hard right then—as one of the guards took me by the arm and started leading me away—how mad pretty my mom is. For real, man, it’s like someone’s picture you’d see in one of them magazines laying around the dentist’s office. Or on a TV show. And she’s actually my moms.

I looked over my shoulder as they walked me through the gate, but she still wasn’t looking at me. It’s okay, though. I understood why.

It’s ’cause of what I did.

June 1

I’ll put it to you like this: I’m about ten times smarter than everyone in Juvi. For real. These guys are a bunch of straight-up dummies, man. Take this big black kid they put me in a cell with, Rondell. He can’t even read. I know ’cause three nights ago he stepped to me when I was writing in my journal. He said: “Yo, Mexico, wha’chu writin’ ’bout in there?”

“Whatever I

wanna

write about,” I said without looking up. “How ’bout

them

apples, homey?”

He paused. “What you just said?”

I shook my head, told him: “And Mexico’s a pretty stupid thing to call me, by the way, considering I’ve never even

been

to Mexico.”

His ass stood there a quick sec, thinking about what I’d just said to him—or at least trying. Then he bum-rushed me. Shoved me right off my chair and onto the ground, pressed his giant grass-stained shoe down on my neck. He said: “Don’t you never talk like that to Rondell again. You hear? Nobody talk to Rondell like that.”

I tried to nod, but he had my neck pinned, so I couldn’t really move my head. Couldn’t make a sound either. Or breathe too good.

He swiped my journal off the table and stared at the page I was writing, his kick weighing down on my neck. And I’m not gonna lie, man, I got a little spooked. Rondell’s a freak for a sixteen-year-old: six foot something with huge-ass arms and legs and a face that already looks like he’s a grown man. And I’d just written some pretty bad stuff about him in my journal. Called him a retarded ape who smelled like when a rat dies in the wall of your apartment. But at the same time I almost

wanted

Rondell to push down harder with his shoe. Almost

wanted

him to crush my neck, break my windpipe,

end my stupid-ass journal right then and there. I started imagining the shoe pushing all the way through, rubber hitting cement. Them telling my moms what happened as she stood with the phone cupped to her ear in the kitchen, crying but at the same time looking sort of relieved, too.

After a couple minutes like that—Rondell staring at the page I’d been writing and me pinned to the nasty cement floor of our cell—he tossed the journal back on the table and took his foot off my neck.

And that’s how I knew he couldn’t read. Dude was staring right at the sentences I’d just written about him, right? And he didn’t do nothin’. Just hopped up on his bunk, linked his fingers behind his head and stared at the paint-chipped ceiling.

What Rondell Thinks About:

There was a long silence in our cell as I got up off the floor and sat back in the chair, tried to stretch out my neck and jaw. Then Rondell said: “Hey, Mexico.”

I rolled my eyes. Like we were gonna be boys after he just tried to kill my ass.

“Yo. Mexico.”

People are straight-up ignorant, man.

He leaned over to look at me. “Mexico! I’m talkin’ to you, man!”

“What!” I shouted back. “Go on, man. Talk. Damn.”

“Yo, you think God could really see the stuff you do down here? Even when you locked up like me and you is?”

“I think he sees about as much as Santa Claus,” I said, opening my journal back up, ripping out my last entry and crumpling it in a ball.

He laid back down, stared at the ceiling again. “’Cause I been thinkin’ about that lately. If he could see me even when

I’m in here. Behind bars. I been thinkin’ he maybe don’t like what he see too much.”

I looked up at Rondell’s bunk, stared at his big black leg hanging off the bed. I looked at my brown arm and then back at his leg. It was probably the blackest damn thing I’d ever seen in my life—and more than half my school back in Stockton is either black kids or Mexicans like me. You ever wonder why some people get so much darker than others? It’s about people’s genes, I know. And how all the continents were once connected or whatever. But how’d it start? Who was the first person to come out looking all different from everybody else? Sometimes I trip on little shit like that.

“Wha’chu think, Mexico?”

He couldn’t see me, but I shrugged anyway, told him: “I don’t think any of us know

what

he can see, Rondell. You ever think maybe that’s the point?”

And that was it, we didn’t say another word to each other for the next two days. And on the third day, early in the morning, a guard came for me. He slid open our cell door holding a clipboard, looking down at it, and said: “Miguel Castañeda? Grab your stuff and come with me, kid. You’re being transferred.”

“To where?” I said.

“Group home in San Jose. Let’s go.”

Rondell didn’t look down at me while I was gathering up all my stuff. Even though I was being all loud on purpose. Even though I could tell he was awake.

June 2

I’ll tell you this: my brother Diego’s a trip, man. He’s probably the quickest kid you could ever meet when it comes to

making up a lie. I’m not playing, yo, he could do it right there on the spot. Fool anybody, anytime. Anyplace.

Take the morning Principal Cody caught me and him fighting in the hall three months before I got locked up—Diego was in eleventh grade, I was in tenth. The bell had just rung and we were still going at it pretty good, like we always did: pushing and wrestling and landing an occasional fist to each other’s neck or rib cage (we never hit each other in the face, though; that was Diego’s one rule). He was pissed at me because I forgot to bring our money for the school field trip to see the Stockton Ports play baseball. Left it sitting right there on the kitchen table next to our empty cereal bowls. Or maybe that was the time he found out I rode his dirt bike up and down the levee in the rain without asking, got mad mud all over his spokes and tires and the bottom part of his frame. I don’t remember exactly why we were fighting that day, but right in the middle of it Principal Cody blew his whistle and said, “What the hell’s going on here!”

Me and Diego separated quick, turned to Principal Cody, straightening out our plain white T-shirts.

I was scared as hell ’cause Moms had just told me and Diego that if we got one more detention she was gonna ship us down to Gramps’s place in Fresno, where they pick strawberries and raisins and figs all day under a sun so damn hot it looks blurry. Me and Diego did it for one week last summer and we pretty much almost died, man. I’m not even playing. And all Gramps did was laugh the whole time. He told us in Spanish that we were tired ’cause we weren’t real Mexicans like everyone else who was out there picking in his group. We were Americans. Told us we might be dark on the outside, but inside we were white like a couple blond boys from Hollywood. And then he laughed some more and so did all his buddies.

Like pretty much every time my gramps says something, I only understood half the words, but as soon as the old man went back to the picking, Diego filled in the blanks.

Diego’s Play:

Anyways, there was Principal Cody scowling at us, right? Freckled-ass arms folded, stupid whistle hanging from a red string around his neck. But Diego’s mad quick, like I told you. He reached into his backpack and pulled out a copy of

West Side Story

, some play his English teacher was about to put on in front of the whole school.

“My little brother’s helping me rehearse, sir,” he said. “Mrs. Nichols thinks I could maybe play that guy Action, the one that starts all the fights. She says bein’ in a play would maybe be a good outlet. My moms thinks so, too.”

Principal Cody looked at me.

I nodded—even though I didn’t know what the hell Diego was talking about.

He looked at my bro again. “Well, I didn’t know you had an interest in the theater, son.”

“It started with this one right here, sir,” Diego said, flipping through the playbook.

“Well, that doesn’t surprise me at all.

West Side Story’s

a classic.”

“I don’t even mind the singing and dancing parts.”

Principal Cody unfolded his arms and took the playbook from Diego. He flipped through the pages himself and said: “My wife and I caught a production of this musical in New York City back in ’74. Right after we were married.” A big smile came on his face.

“You been all the way to New York?” Diego said.

Principal Cody laughed a little under his breath, said: “Many times.”

“That’s awesome, sir.”

I kept looking back and forth between them, thinking how crazy it was that me and my bro were this close to a principal and we weren’t even in trouble. Dude was actually

smiling

. The only other times I’d been this close to one is when I got my ass sent to his office ’cause of something I did in class or if I got caught stealing from the campus store or whatever. And trust me, on those times there wasn’t no smiling involved.