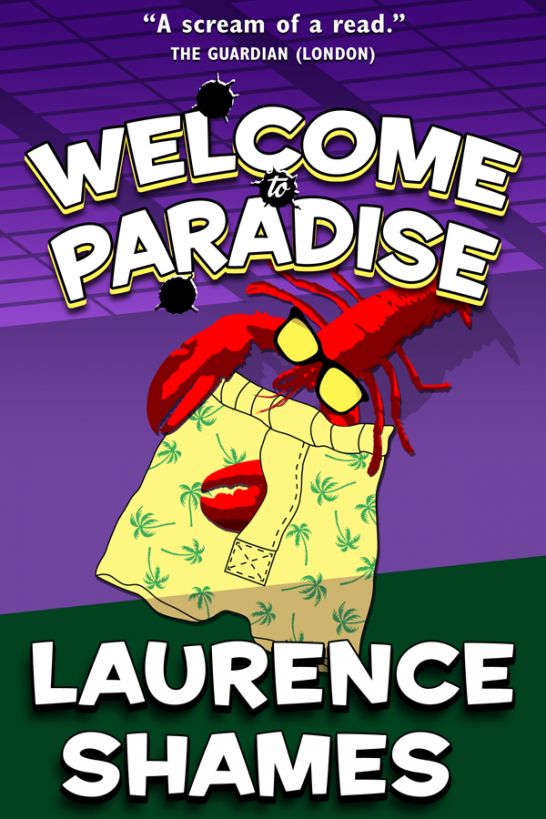

Welcome to Paradise

“

Shames can be as absurd and hilarious as Carl

Hiaasen at his most uproarious…[The] mayhem would not disgrace the

Marx Brothers. A scream of a read.”

—The Guardian

(London)

“

The author sets up the inevitable comedy of errors

like a dealer laying out a winning hand of cards…The Key West

locale was so real I felt my hair frizz.”

—The Los

Angeles Times

“

Laurence Shames mixes sun and fun, wise guys and

dumb guys, smart gals and bad gals with such wit and style it makes

you want to head straight to Key West and join the

party.

”—The Orlando Sentinel

By

Laurence Shames

Smashwords Edition

Copyright ©1999 Laurence Shames

Originally published by Villard Books, a division of

Random House, Inc.

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment

only. This ebook may not be resold or given away to other people.

If you would like to share this book with another person, please

purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading

this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your

use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your

own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this

author.

To Marilyn,

who laughs

with love

PROLOGUE

"Was the, clams," said Nicky Scotto.

"Ya sure?" said Donnie Falcone. Skeptically,

he tugged on a long and fleshy earlobe. "Ya sure it was the

clams?"

"Hadda be the clams." Nicky sipped anisette

and looked vaguely toward the window of Nono's Pasticceria. Nono's

was on Carmine Street, two steps below the sidewalk. Half a century

of exhaust fumes had tinted its front window a restful bluish gray.

People talked softly in Nono's. Never loud enough to be heard above

the steaming of the milk. Nicky put his glass down, said, "Fuck

else could it'a been?"

Carefully, fastidiously, Donnie broke a

biscotto

, herded up crumbs with the flat of his thumb. He

hated when crumbs got stuck in the fibers of his big black

overcoat. "How should I know? What else j'eat?"

Nicky winced just slightly and softly belched

at the recollection of the catastrophic meal. He pictured the

breadsticks, the drops of wine on the tablecloth. His fist still

pressed against his lips, he said, "Minestrone."

"Minestrone," echoed Donnie. "Ya don't puke

off minestrone."

"Hadda be the clams," Nicky said once more.

He leaned back in the booth, smoothed the creamy mohair of his

jacket. Dark and thickly built, he was handsome until you looked a

little closer. The jaw was square but just a little heavy, the

black eyes too close to the thick and slightly piggish nose.

Donnie kept his eyes down on his pastry

plate. "Ya sure you're not just lookin' for a reason to get mad at

Al?"

When Nicky was agitated, his voice got softer

instead of louder. His throat squeezed down like a crimped hose and

words came out with the razzing purr of a muted trumpet. "I don't

need another fuckin' reason to be mad at Al."

Donnie thought it best to leave it right

there. "Okay. What else j'eat?"

Nicky absently ran fingertips against the

wall. The wall was covered with small white tiles, broken up with

ranks of gold and black at shoulder level. "Broccoli rabe," he

said. "Scallopini veal, lemon sauce. Some pasta shit, little hats,

like."

Donnie said, "Orecchiette?"

"Fuck knows?" said Nicky. "Look, I didn't

come here to discuss macaroni shapes, okay? I come here to tell ya

what that fuck Al did to me."

"A few bad clams," said Donnie.

"Happens."

"Look, when I had the fish market, I did the

right thing. I didn't give bad clams to places where friends of

ours was gonna eat."

"Nicky. How is Al supposed to know you're

gonna be eatin' in some hotel up inna Catskills?"

The question slowed Nicky down. His

fingernails tickled the grout between the tiles.

Donnie went on. "Truth, Nicky, I don't see

you inna fuckin' Catskills either. It's a Jew place."

"Used ta be," said Nicky. "Now it's

everything. Hotels for queers. For Puerto Ricans. Couple good

Italian places, you know that."

"Okay, okay. But whaddya do up there? Play

shuffle- board?"

Embarrassed, Nicky said, "Ya look at

leaves."

"Leaves?"

"I tol' ya, Donnie," Nicky said. "My

mother-in-law, it was her seventieth. My wife says, 'She loves the

autumn. Let's take her to the leaves.' So I say okay. The old broad

wantsta look at leaves, I'm tryin' to be nice. Wha' could I tell

ya—this is who I am."

Donnie drained his espresso, motioned for

another. From behind his arm, he said, "It ain't the clams. You're

mad 'cause Tony Eggs took the fish away from you and gave it to Big

Al."

Nicky tugged at the collar of his turtleneck,

twisted his head around in a circle. "'Course I'm mad," he finally

admitted. "Fuck wit' a man's livelihood, who ain't gonna be mad?"

There was a silence, and when the stocky man spoke again he could

not quite hide a real sorrow and bewilderment. "Why'd he do it,

Donnie?"

Donnie shrugged. He had a long thin face and

a long thin neck, and when he shrugged, his shoulders had a lot of

ground to cover. His skin had a grayish-yellow cast and his usual

expression was distantly amused yet mournful. "I ain't got a

clue."

"Come on—the man's your uncle."

"Great-uncle," corrected Donnie, and came

close to revealing some pique of his own. "An' ya see how close we

are. Me, I'm still hustling window-cleaning contracts inna fuckin'

garment district."

Nicky made a vague and universal griping

sound.

Donnie sipped coffee and quietly went on.

"Look, the market's Big Al's now. Ya gotta let it go."

"This ain't about the market."

"I wish I could believe that."

"What this is about is that he poisoned me.

Poisoned alla us."

Donnie's flat lips stretched out and came

close to smiling. He wiped his mouth instead. "The t'ree a you in

that hotel room—"

"Suite. It was a suite. Two bedrooms. Two

bat'rooms. I thought two would be enough."

There was a pause. Outside on Carmine Street,

taxis went by, the clatter of trucks filtered in from Seventh

Avenue. The milk steamer hissed and Nicky got madder. Revolted.

Humiliated. "Well," he went on, "two bat'rooms wasn't enough. The

wife, the old lady—disgusting. Dignity? Tell me about dignity when

you're leakin' both ends, hoppin' to the toilet wit' your pj's down

your ankles. When your wife has to crawl over ya to get to the

bowl."

"Nicky, it was just bad luck. Coulda happened

to any—"

But Nicky was not to be hushed. Air wheezed

through his pinched windpipe. "Ol' lady ends up whaddyacallit,

intravenous. Happy birt'day, Ma. Camille, skinny marink to begin

wit', she drops six pounds. Me, I ain't right for a week. A week,

Donnie! Cramps, runs, white shit on my tongue. Taste in my mouth

like somethin' died. I tell ya, Donnie, a week a hell."

Donnie had settled back in the booth, all but

disappearing into his coat. When Nicky finished, he leaned forward,

folded his long neat hands in front of him, and said very softly,

"But, Nicky, why stay mad? I mean, where we goin' wit' this? Ya

gonna ice a guy over some funky seafood?"

Nicky sipped his anisette. His face went

innocent. "Who said anything about icin' anyone? You said that. Not

me."

"I only said—"

"Look, I'm a guy that does the right

thing—"

"You keep sayin' that," Donnie pointed

out.

"—and all I want is that that fuckin' guy

should suffer like I suffered. A week a total misery. Justice.

That's all I want. Zat too fuckin' much t'ask?"

"Justice? Yeah," said Donnie. He blotted up

some crumbs. "So whaddya want from me?"

"Help. Advice. Like, ways to ruin his

life."

"Nicky, I don't want no part a this. Besides,

it's gonna have to wait."

"What has to wait? Wait for what?"

"Big Al's goin' outa town I heard. Goin' on

vacation."

Nicky rubbed his chin. "Hey, I was on

vacation, too. A guy can't be mizzable on vacation?" He paused. He

brightened slightly and his small black eyes squeezed down.

"Where's he goin' on vacation?"

"Flahda," Donnie said reluctantly. "Key West

is what I heard."

"Flahda," Nicky intoned. He drained his

anisette, wrapped hot hands around the glass. He lifted up one

curly eyebrow. "Flahda. Far away. That's nice. That's like the best

advice you coulda gimme."

"Hey—"

"Flahda. Vacation. Far away from

everything."

"You never heard it from me," said

Donnie.

Nicky said, "So happens I got friends in

Flahda."

1

"Why we gotta, drive?" said Katy Sansone, who

was twenty-nine years old and Big Al Marracotta's girlfriend.

She was bustling around the pink apartment

that Big A1 kept for her in Murray Hill. It was not a great

apartment, but Katy, though she had her good points, was not that

great a girlfriend. She complained a lot. She went right to the

edge of seeming ungrateful. She had opinions and didn't seem to

understand that if she refreshed her lipstick more, and answered

back less, she might have had the one-bedroom with the courtyard

view rather than the noisy, streetside studio with the

munchkin-sized appliances. Now she was packing, roughly, showing a

certain disrespect for the tiny bathing suits and thong panties and

G-strings and underwire bras that Big A1 had bought her for the

trip.

"We have to drive," he said, "because the

style in which I travel, airports have signs calling it an act of

terrorism."

"Always with the guns," she pouted. "Even on

vacation?"

"Several," said Big Al. "A small one for the

glove compartment. A big one under the driver's seat. A fuckin'

bazooka inna trunk." He smiled. "Oh, yeah—and don't forget the big

knife inna sock." He was almost cute when he smiled. He had a small

gap between his two front teeth, and the waxy crinkles at the

corners of his eyes suggested a boyish zest. When he smiled his

forehead shifted and moved the short salt-and-pepper hair that

other times looked painted on. Big A1 was five foot two and weighed

one hundred sixteen pounds. "Besides," he added, "I wanna bring the

dog."

"The daw-awg!" moaned Katy.

Big A1 raised a warning finger, but even

before he did so, Katy understood that she should go no further.

Certain things were sacred, and she could not complain about the

dog. Its name was Ripper. It was a champion rottweiler and a total

coward. It had coy brown eyebrows and a brown blaze on its square

black head, and it dribbled constantly through the flubbery pink

lips that imperfectly covered its mock-ferocious teeth. A stub of

amputated tail stuck out above its brown-splashed butt, and its

testicles, the right one always lower than the left, hung down and

bounced as though they were on bungees. It was those showy and

ridiculous nuts, she secretly believed, that made A1 dote so on the

dog.

She kept packing. High-heeled sandals.

Open-toed pumps. Making chitchat, trying to sound neutral, she

said, "So the dog's already in the car?"

Big A1 nodded. "Guarding it." Again he

smiled. Say this for him: he knew what gave him pleasure. He had a

huge dog gnawing on a huge bone in the backseat of his huge gray

Lincoln. He had a young girlfriend packing slinky things for a

weeklong Florida vacation—a week of sun, sweat, sex, and lack of

aggravation. For the moment he was a happy guy.

Katy snapped her suitcase closed and

straightened out her back. She was five foot eleven, and A1 had

told her never to insult him by wearing flats. Standing there in

heels and peg-leg pants, she looked a little like a missile taking

off. Long lean shanks and narrow hips provided thrust that seemed

to lift the dual-coned payload of chest, which tapered in turn to a

pretty though small-featured face capped by a pouf of raven

hair.

For a moment she just stood there by her

suitcase, waiting to see if A1 would pick it up. Then she picked it

up herself and they headed for the door.

His face was on her bosom the whole elevator

ride down to the garage. Vacation had begun.

*

Across the river in suburban New Jersey, on the vast

and cluttered selling floor of Kleiman Brothers Furniture on Route

22 in Springfield, a ceremony was in progress.

Moe Kleiman, the last survivor of the

founding brothers, had taken off his shoes and was standing,

somewhat shakily, on an ottoman. He stroked his pencil mustache,

fiddled with the opal tie tack that, every day for many years, he'd

painstakingly poked through the selfsame holes in the selfsame

ties, and gestured for quiet. Benignly, he looked out across the

group that he proudly referred to as the finest sales staff in the

Tri-State area. For a moment he gazed beyond them to the store he

loved: lamps with orange price tags hanging from their covered

shades; ghostly conversation nooks in which a rocker seemed to be

conferring with a La-Z-Boy; ranks of mattresses close-packed as

cots in a battlefield hospital.