Welcome to Your Brain (14 page)

Read Welcome to Your Brain Online

Authors: Sam Wang,Sandra Aamodt

Tags: #Neurophysiology-Popular works., #Brain-Popular works

Campbell, who brought mysticism together with loosely interpreted scientific results to

produce a bestseller that influenced public policy. The next year, Georgia governor Zell

Miller played Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” to the legislature and requested $105,000 to send

classical music CDs to all parents of newborns in the state. The legislators approved his

request, failing to notice that it made no sense to argue that music would lead to lifelong

intelligence gains in babies based on an effect that lasts less than fifteen minutes in adults.

Florida legislators soon followed suit, requiring state-funded day care centers to play

classical music every day.

By now, the idea that classical music makes babies smarter has been repeated countless

times in newspapers, magazines, and books. The idea is familiar to people in dozens of

countries. In the retelling, stories about the Mozart effect have progressively replaced

college students with children or babies. Some journalists assume that the work on college

students applies to babies, but others are simply unaware of the original research.

In 1999, another group of scientists repeated the original experiment on college students

and found that they could not duplicate its results. It hardly matters, though, that the first

report had been incorrect. What’s important is that no one has tested the idea on babies.

Ever.

While playing classical music for your kids isn’t likely to improve their brain

development, something else will—having them play music for you. Children who learn to

play a musical instrument have better spatial reasoning skills than those who don’t take

music lessons, maybe because music and spatial reasoning are processed by similar brain

systems. Filling your house with music may indeed improve your children’s intelligence—

as long as they aren’t passive consumers, but active producers.

You’re probably more interested in how the brain grows under normal circumstances. The early

stages of brain development don’t require experience at all—which is fortunate, since they mostly

occur inside the mother, where there’s not a lot of stimulation available. This is when the different

areas of the brain form, when neurons are born and migrate to their final positions, and when axons

grow out to their intended targets. If this part of the process goes wrong, because of drugs or toxins in

the mother’s body or genetic mutations in the fetus, severe birth defects often result. Prenatal brain

development is sufficient to permit many basic behaviors, such as withdrawal from a rapidly

approaching object.

After the baby is born, sensory experience starts to become important for some aspects of brain

development. In any normal environment, though, the odds-on bet is that most of the necessary

experience is easily available. For example, as we saw in the story of Mike May (

Chapter 6)

, the

visual system can’t develop correctly without normal vision, but that experience happens effortlessly

for anyone who can see. We don’t have to send our kids to vision enrichment classes to make sure

that these parts of their brains develop correctly. Scientists call this type of dependence on the

environment “experience-expectant development,” and it’s by far the most common way that our

experiences influence how our brains grow. Along the same lines, readily available sensory

experience is necessary for the correct development of sound localization and for mother-infant

bonding.

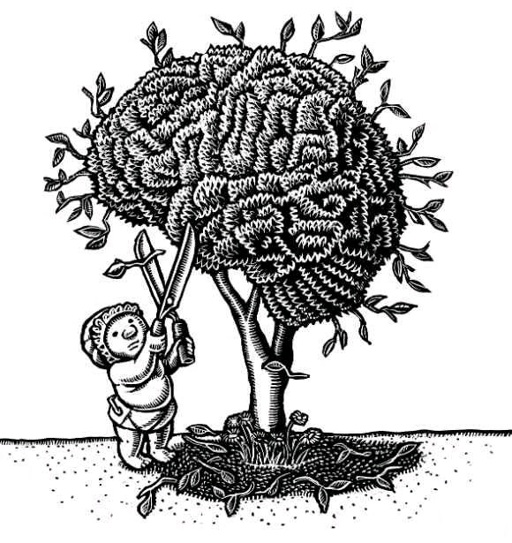

Sensory experience works by influencing which neurons receive synapses from the incoming

axons. You might think that the patterns of activity in the growing axons would determine where new

synapses are formed, but the brain doesn’t take this approach. Instead, it produces a huge number of

relatively nonselective connections between neurons in the appropriate brain areas during early

development and then removes the ones that aren’t being used enough over the first two years of life

(in people). If the brain were a rosebush, early life experience would be the pruning system, not the

fertilizer.

Experience-expectant development is also important for the development of a child’s intelligence,

as the effects of serious environmental deprivation show. There’s some evidence that the ability to

learn or to reason may also be enhanced by exposure to intellectually stimulating activities (what we

often call enrichment), but exactly how much is a tricky question. A key element may be the difference

between learning an active skill, such as playing a musical instrument, as opposed to passive

exposure, such as listening to music (see

Myth: Listening to Mozart makes babies smarter

).

Over the past several decades, the average intelligence quotient (IQ) in many countries has

increased, as we’ll discuss further in

Chapter 15

, suggesting that something about modern life is

producing kids who do better on these tests than their parents. This effect is strongest among children

with lower-than-average IQs. We don’t know the degree to which these IQ gains in less intelligent

children are attributable to changes in their intellectual environment versus better prenatal care and

early childhood nutrition, though we would bet that all of these factors are important.

The evidence that environmental enrichment helps the brain has mainly come from research on

laboratory animals. For instance, mice that are housed with other mice and an assortment of toys that

are changed frequently have larger brains, larger neurons, more glial cells, and more synapses than

mice that are housed alone in standard cages. The enriched animals also learn to complete a variety

of tasks more easily. These changes occur not only in young mice, but also in adult and old mice.

Unfortunately, there’s ambiguity about how to apply this work to people; we don’t know how

enriched we are compared to lab animals. Lab animals live in a very simplified environment; they

rarely have to navigate through complicated places to search for food or find someone to mate with,

and they certainly don’t have to write college application essays. In practice, then, this research is not

so much about the positive effects of enrichment on the brain but about the negative effects of

deprivation in the typical laboratory environment. All this information together suggests that society

should get a high return on investing in the enrichment of the lives of kids who are relatively

deprived. Further improvements for kids whose lives are already enriched may do little or no good.

Did you know? Early life stress and adult vulnerability

Some people just seem to be more mentally resilient than others. Part of the explanation

may be that early experiences can increase the responsiveness of the stress hormone system

in adulthood. This is true for rats, for monkeys, and probably for people as well.

In pregnant rodents, stress increases the release of glucocorticoid hormones. This

hormone exposure can lead to a variety of later problems in the offspring. They’re typically

born smaller than normal animals and are more vulnerable to hypertension and high blood

glucose as adults. These prenatally stressed animals grow up to exhibit more anxiety

behaviors and are less able to learn in laboratory tests.

The good news is that getting a lot of maternal care in the first week of life can make

rats less vulnerable to stress as adults. Maternal grooming permanently increases the

expression of genes that encode stress hormone receptors in the hippocampus. Because

activation of these receptors reduces the release of stress hormones, good mothering makes

the rat pups less fearful later in life by reducing the responsiveness of their stress hormone

system. Poor early mothering has the opposite effects. Artificially increasing the expression

of these genes or housing the animals in an enriched environment reverses the hormonal

effects of poor mothering in adult rats. Maternal grooming of pups also influences both

excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter systems in adulthood.

Early stress may also increase vulnerability in humans. Abuse, neglect, or harsh,

inconsistent discipline in early life increases the later risk of depression, anxiety, obesity,

diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. It also heightens the responsiveness of the stress

hormone system in adulthood. However, scientists don’t know whether stress causes

changes in the brains of people similar to the changes observed in rats, nor do they know

whether these effects might be reversible by drug treatments in adults.

As we’ll see in the next chapter, some aspects of brain development require very specific types of

experience. The brain is not a blank slate but instead is predisposed at certain times to learn

particular types of information. Although the specific language you speak as an adult depends on

whether the people around you communicate in Swahili or Swedish, your brain is especially

prepared to learn language at an early age. Your genes determine how you interact with your

environment, including what you learn from it.

Growing Up: Sensitive Periods and Language

Babies are incredible learning machines. You probably know that there’s something unique about

young brains when it comes to learning. But you may not appreciate that their abilities are very

specific. Babies aren’t sponges waiting to soak up anything that happens to them. They come into the

world with brains that are prepared to seek out certain experiences at defined developmental stages.

The times early in life when experience (or deprivation) has a strong or permanent effect on the

brain are called sensitive periods in development. They’re the reason that people who learn a

language as adults are more likely to speak with an accent. People can still learn when they’re older,

of course, but they learn some things less thoroughly, or in a different way. On the other hand, many

types of learning are equally easy throughout life. There’s no special advantage to being young if you

want to study law or learn how to knit, but if you want to be a really good skier or speak a language

like a native, it’s best to learn as a child.

In some ways, sensitive periods can be thought of as being analogous to constructing a home.

When you are building a house, you decide how you want to arrange the bedrooms. Once the house

has been built, changes are much harder. You can rearrange or replace the furniture, but unless you’re

willing to put in an awful lot of work, your floor plan is set.

In the same way, the mechanisms by which brains are built allow some changes to be made much

more easily early in life. Although learning is easier during sensitive periods, it can often still take

place later on. Some people succeed in mastering a second language so that they sound

indistinguishable from native speakers. Even if a language learned in adulthood is completely fluent,

though, brain imaging shows that different, nearby parts of the brain are active when people hear their

two languages. So not only are children better at learning languages than adults, but they can also use

a single area of their brains to support several languages. It’s as if, to support new language

acquisition, adults have to expand into the spare room.

Did you know? Is language innate?

We can’t deny that learning is important for language development—after all, Chinese

babies adopted by American parents grow up speaking English, not Mandarin—but an

influential theory suggests that the brain is not infinitely flexible about what types of

language it can learn. Instead, people seem to be constrained by a set of basic rules for

constructing sentences that is hardwired into the brain.

The universal grammar idea was originally proposed by the linguist Noam Chomsky,

who said that the languages of the world are not as different as they seem on the surface.

The vocabulary may vary enormously from one language to the next, but there is a relatively

limited range of possibilities for how sentences may be constructed. In this view, the

grammar of a particular language is thought to be defined by a few dozen parameters, such

as whether adjectives are placed before the noun, as in English, or after the noun, as in

Spanish. It’s as if babies learn to flip switches for various parameters in their brains,

yielding the full grammatical complexity of a language from a small number of simple