Welcome to Your Brain (4 page)

Read Welcome to Your Brain Online

Authors: Sam Wang,Sandra Aamodt

Tags: #Neurophysiology-Popular works., #Brain-Popular works

behavior might accompany schizophrenia or bipolar disorder—but even then only rarely.

A slightly less implausible scenario occurs in the charming

Desperately Seeking Susan

(1985), in which Rosanna Arquette plays a bored housewife who loses her memory and

experiences severe confusion. Although the selective loss of identity after a head injury is

implausible, one aspect of what happens next contains a grain of truth. A personal ad and a

found article of clothing help Arquette invent a story about her lost identity. She goes on to

assume the life and obligations of an adventuress on the lam, played by Madonna. Victims

of memory loss will often fill in lost information by creating plausible memories, an act of

confabulation that creates the illusion of normal, continuous memory.

Before 1901, the trail of the idea starts to get cold. What enterprising writer first put to paper the

thought of a head blow leading to amnesia? The notion does represent an advance: it acknowledges

the brain as the seat of thought. After all, Shakespeare presented acts of magic as agents of mental

change. Think of Titania in

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

, who is induced by the prankish Puck’s

magic love drops to fall in love with Bottom, who has the head of a donkey.

Perhaps we have unfairly made fun of these depictions of memory loss. After all, psychiatric

disorders show more diverse symptoms than the strictly neurological disorders stemming from

physical injury or disease. For instance, a psychiatric patient might show selective amnesia in very

specialized ways. Also, transient memory loss is known to occur spontaneously, possibly because of

miniature strokelike events (see

Chapter 29)

. But Hollywood usually tells us that the memory loss

starts with an injury or traumatic event, and in this regard the targets of our criticism are fair game.

Cinema may be ripe for scientific criticism, but it does provide insight into how people think the

brain works.

A conceptual underpinning to many cinematic misconceptions is an idea we will call “brains are

like old televisions.” Consider a common dramatic convention: after a blow to the head induces

memory loss, memory can be restored by a second blow to the head. The existence of this myth points

to unspoken assumptions we make about how the brain works. For the second-blow hypothesis to be

true, damage to the brain would have to be reversible. Since the likeliest cause of amnesia from a

head injury would be a fluid accumulation that pushes on the brain, a therapeutic benefit from a

second injury would be pretty unlikely, to say the least.

A likely source of the second-blow idea is our everyday experience with electronic devices,

especially old ones. It’s well known that hitting an old television in just the right way can sometimes

get it to work again. These old devices usually have loose or dirty electrical contacts, suggesting that

a properly aimed blow might help reseat a connection and thus restore function. The basic problem

here is that brains do not have loose connections as such; synapses join neurons together so tightly

that no blow, short of a totally destructive injury, would ever “loosen” them.

Many moviemakers seem to think that brains are understood and organized well enough that

neurosurgery is useful as a means of repairing memory loss. It is true that neurosurgery can reduce

immediately life-threatening conditions, such as the accumulation of fluid or a tumor that compresses

the brain. These conditions would usually be accompanied by severe confusion (as in a concussion)

or loss of consciousness. Such a surgery needs to be performed immediately after the problem occurs,

presenting screenwriters with the dilemma that the dramatic value of any amnesia would have to be

compressed into the trip from the injury site to the hospital. Otherwise neurosurgery is more likely to

be an accidental cause of memory loss than a cure for it.

Did you know? Can memories be erased?

In

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

(2004), the main character seeks to obliterate

memories of a relationship gone wrong by going to a professional outfit that provides such

a service for a price. In the movie, the character is strapped down and goes to sleep while

technicians rummage through his head. They play back memories and pick out the ones that

need to be erased.

One idea implicit in this sequence is that neural activity somehow encodes explicit,

movielike representations of remembered experiences. Perhaps the logic is not entirely

cracked—experience does appear to be reduced and compressed as it is converted to

something that the brain can store—but the result is not a full replay of the event (see

Chapter 1

). Recollection of a visual scene does trigger brain responses that resemble in

some ways the responses that arise from viewing a scene for the first time. Another part is

less fantastic than it may sound: the idea that one can locate an offending memory, play it

back, then erase it like an unwanted computer file. Research in the past few years suggests

that recollection of a memory also reinforces the memory. There is good evidence that we

“erase” and “rewrite” our memories every time we recall them, suggesting that if it were

ever possible to erase specific content, playing it back first might be an essential

component.

In a more realistic (but totally revolting) depiction of brain injury, we have the sequel to

The

Silence of the Lambs

(1991),

Hannibal

(2001), in which gradual invasion (oh, let’s not mince words

—the cutting up and cooking of a person’s brain) causes progressive loss of function. Putting aside

the difficulty of carrying out such brain surgery without killing the patient, here at least we have a

situation in which damage to the brain leads to proportional loss of function.

In the thicket of misleading and silly depictions of the brain in popular entertainment, a few

counterexamples stand out in which the science is accurate. Scientific accuracy is not necessary for a

satisfying dramatic experience, of course, but it does seem possible to maintain accuracy, attract

critical approbation, and experience commercial success all at once. Various brain disorders are

depicted both accurately and sympathetically in the movies

Memento

,

Sé Quién Eres

,

Finding Nemo

,

and

A Beautiful Mind

.

Memento

(2000) accurately describes the problems faced by Leonard, who has severe

anterograde amnesia. Due to a head injury, Leonard cannot form lasting new memories. In addition,

he has difficulty retaining information held in immediate memory and, when distracted, loses track of

his train of thought. The effect is cleverly induced in the viewer’s mind by showing the sequence of

events in reverse order, starting with the death of a character, and ending with a scene that reveals the

meaning of all the subsequent events.

The symptoms suffered by Leonard are similar to those experienced by people with damage to the

hippocampus and related structures. The hippocampus is a horn-shaped structure that in humans is

about the size and shape of a fat man’s curled pinkie finger; we have one hippocampus on each side

of our brains. The hippocampus and the parts of the brain that link to it, such as the temporal lobe of

the cerebral cortex, are needed for the short-term storage of new facts and experiences. These

structures also seem to be important for eventual long-term storage of memories; patients with

temporal lobe or hippocampal damage, such as from a stroke, often are unable to recall events in the

weeks and months before the damage.

In

Memento

, the accident that triggers Leonard’s amnesia is depicted with remarkable fidelity,

right down to the part of his head that receives an injury, the temporal lobe of the cortex. The resulting

loss of function is also accurate, with the possible exception that unlike many patients with similar

damage, he is aware of his problem and can describe it. The most famous patient with hippocampal

and temporal lobe damage, known only as HM, is not so lucky (or perhaps he is luckier). Since he

had an experimental surgery to prevent epileptic seizures, HM lives in a perpetual now, continually

greeting people as if for the first time, even if he has spoken to them countless times before (see

The 2000 Spanish thriller

Sé Quién Eres

(I Know Who You Are) presents the case of Mario,

whose memory loss stems from Korsakoff’s syndrome, a disorder associated with advanced

alcoholism. Mario cannot recall anything that happened to him before 1977, has difficulty forming

new memories, and is often confused. Yet his psychiatrist finds herself drawn to him. In Mario’s

case, his memory defects result from damage to his thalamus and mammillary bodies, which is caused

by thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency resulting from the long-term malnutrition that often accompanies

severe alcoholism.

A final example of memory loss in the movies comes from the animated feature

Finding Nemo

(2003). The sufferer in this case is not a human being, but a fish. Dory is friendly but has severe

difficulty forming new memories. Like Leonard, she loses her train of thought when distracted. We

could complain that it is unrealistic to expect much cognitive sophistication from a fish, but

considering the egregiousness of the worst cinematic offenses, we will score this as a minor

infraction. What is realistic in this movie is the feeling of being lost that Dory experiences as she

finds her way through life, and the way that she can be annoying, even (and perhaps especially) to

those close to her.

Did you know? Schizophrenia in the movies—

A Beautiful Mind

A Beautiful Mind

(2001) dramatizes the life of the mathematician John Nash, presenting

the experience of descending into schizophrenia in great detail. The Nash character (in a

somewhat loose adaptation of the real Nash) experiences hallucinations and starts to

imagine causal links between unrelated events. His growing paranoia about the motives of

those around him and his inability to critically reject these delusions gradually alienate him

from colleagues and loved ones.

These are classic signs of schizophrenia, a disorder that is caused by changes in the

brain induced by disease, injury, or genetic predisposition. Schizophrenia typically strikes

people in their late teens and early twenties and affects more men than women. As many as

one in one hundred people experience symptoms of schizophrenia at some point in their

lives. The hallucinations experienced by the Nash character in the movie are visual; the

real-life Nash has experienced auditory hallucinations of a similar nature.

While much of the movie is scientifically accurate, one significant error is that Nash is

cured by the love of a good woman. Schizophrenia is not a romantic event; it is a physical

disorder of the brain. Some degree of recovery is possible: patients may have periods of

normal function interspersed with symptomatic periods, and symptoms disappear in as

many as one in six schizophrenics. The reasons for remission, however, are currently not

known. The error made in the movie is reminiscent of the old myth that schizophrenia is

caused by a lack of mother love, an idea that has no support, is refuted by evidence, and

makes mothers—and other loved ones—of schizophrenics feel guilty for no good reason.

This brings us to a striking recurring theme in the accurate depiction of memory loss: the

sympathetic portrayal of the sufferer. In inaccurate depictions, the victim is often regarded as a figure

of fun or even ridicule. However, the plight of accurately portrayed sufferers is almost always

rendered poignantly and, in the best cases, captures the feeling of what it is like to have a disorder.

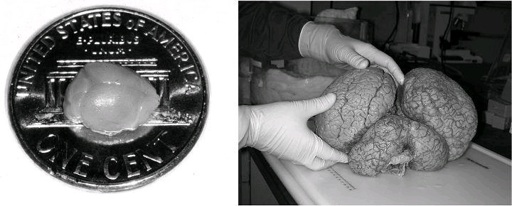

Thinking Meat: Neurons and Synapses

In his short story “They’re Made Out of Meat,” Terry Bisson describes alien beings with electronic

brains who discover a planet, Earth, on which the most sophisticated organisms do their thinking with

living tissue. The aliens refer to brains as “thinking meat.” (Gross, we know.) The idea that your