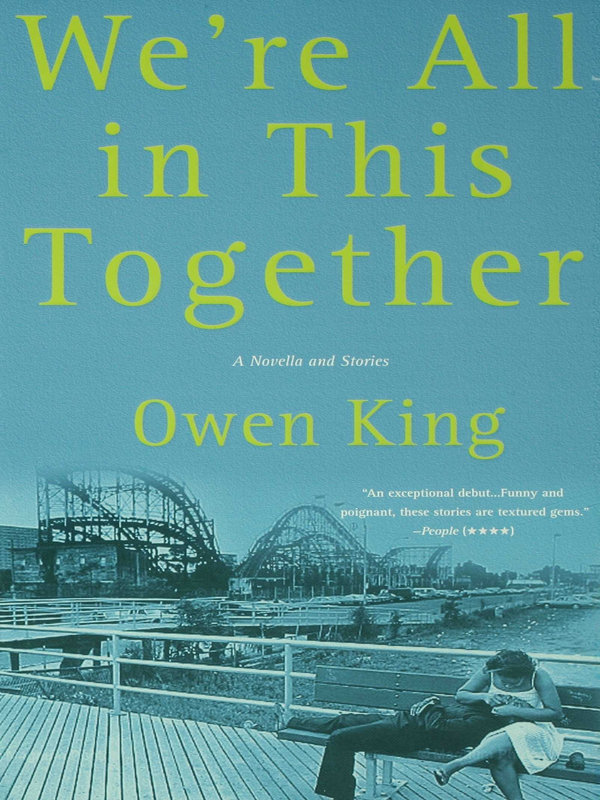

We're All in This Together

Read We're All in This Together Online

Authors: Owen King

We're All in This Together

We're All

in This

Together

A Novella and Stories

Owen King

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright © 2005 by Owen King

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from

the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury

USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury USA are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing

processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the

hardcover edition of this book as follows:

King, Owen.

We're all in this together : a novella and stories / Owen King.—1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58234-588-8

1. United States—Social life and customs—Fiction. 2. Grandparent and child—Fiction. 3. Mothers and sons—Fiction. 4. Teenage

boys—Fiction. 5. Maine—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3611.I5837W47 2005

813'.6—dc22

2005006926

First published in the United States by Bloomsbury in 2005

This paperback edition published in 2006

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Hewer Text Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the United States of America

by Quebecor World Fairfield

For Kelly,

the prettiest girl in Yuma

Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns;

there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do

not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know. And if. one looks throughout the history

of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.

—Donald Rumsfeld on the question of

Iraq and WMDs, February 12, 2002

DON'T MOURN!

When you are a kid, adults are always telling you about their

revelation, the moment when the mist cleared and they saw what

it was they wanted, or finally understood what it was that never

made sense before.

For instance, my grandfather told me that he decided to be a union

organizer after he saw the man who lived next door at the boardinghouse

come home one morning after a late shift at the paper mill,

remove his shoes at the door, and pass them off to his wife, who then

slipped them on and continued out on her way to another job. As the

man handed off his shoes, my grandfather realized that what the man

was actually handing off was his dignity, and that a life without

dignity was no different from a life without

love

—

because how could

a man without dignity bear to love another person, when he must

hate himself so much?

Dr. Vic claimed that he fell in love with my mother when he looked

out his office window one sunny afternoon to see her striding up to

the elderly Catholic priest who sometimes prayed on the sidewalk in

front of the Planned Parenthood office for hours at a time. The old

priest appeared to be swaying slightly; Emma helped him from his

knees over to a bench. After that, she went back inside, and came out

a minute later with a cold bottle of water for the holy man. Dr. Vic

watched it all, and wondered how many times that old crank had

warned my mother that she was on the path to hell, and there she was

anyhow, doing the decent thing to save him from a case of sunstroke,

or worse. Until then I only thought she was beautiful, said Dr. Vic,

but that proved it.

At a rally for striking longshoremen in Portland, my grandmother

said she heard Papa relate the story about his neighbors who had to

share a single pair of shoes, and while she felt compelled by his

words, she didn't fully devote herself to the cause until after the

meeting

—

when he came down from the platform and shook her

hand. Nana had seen other union men talk, and dramatically whip

off their coats, and stomp around in their braces while they railed

against the bosses. She even met one of these big stomping sorts once,

and it was like shaking hands with a liver. When she was introduced

to my grandfather, though, Nana realized immediately that Papa was

different: in spite of his suit, my grandfather wasn't a college boy, or

a

politician

—

he was an actual stevedore, just like her brother and her

uncle. She could tell this by the fine dirt in the creases beneath his

eyes, what her mother used to call "Working Man's Scars." Then

Papa stuck out his hand, said, "How do," and Nana grasped it. He

had clean hands, dry hands. She was moved to think of how hard he

had worked to get himself clean. Finally, she thought, here was a

young man who believed in something.

What I take from these stories is the impression that until that

certain

moment

—

the awakening, the

sign

—

each of us is waiting

outside the life that we are meant for, like a stranger with nothing to

do but sit on the steps until the Realtor arrives. Then she does appear,

charging up the walk, a fury of possibility and jingling keys. She

throws open the door, and hurries you inside, and you know, right

then. This is the place, the one place you really belong.

Except, I think now that for most people, it's more complex than

that. In the moment of realization, maybe the mist doesn't actually

clear, but thicken, taking on color, smell, and taste. Maybe the house

is for sale because it's haunted; maybe every house is haunted.

When Papa saw the man give his wife the pair of shoes, he saw that

something was wrong, but maybe he summed too quickly, and

underestimated the depth of a man's dignity. When my mother

brought the old priest a bottle of water, maybe Dr. Vic bet too high

on Emma's generosity, and too low on the hard-earned pessimism of

a single mother and motivated activist, who undoubtedly worried a

good deal more about the news stories that would follow the death of

a priest on the sidewalk in front of the clinic, than she ever did about

the man actually dying. And was there ever a

time

—

years and years

after she took the clean hand of the dirty soapboxer that day on the

docks

—

that my grandmother wondered just what my grandfather's

effort amounted to, now that they lived in a time and in a place where

it seemed that the filthiest thing you could say about a person was

that they were liberal, that they had a bleeding heart?

Obviously, something was on Nana's mind when she died. After

January, she never again left the guest bedroom, and one morning in

early March, I found her cold. A sour, ponderous expression lay on

her face, a grimace of real dissatisfaction, as if she had been expecting

a surprise, but just maybe not the one she received. Her eyes were

open, too, and fixed on the framed portrait of Joseph Hillstrom that

hung on the wall.

In those last seconds, what did she see in the eyes of labor's truest

martyr? Did she see the cool expression of a sincere organizer? Or

did she see the passionless stare of a killer?

Four months later, in the middle of summer, and with the grass

already grown full and burnt brown on Nana's grave, I saw

something

that surprised me, too. At the time, I understood it couldn't be

real, that it was a hallucination. But, these days, I know better than

to believe my eyes. Sometimes up really is down; sometimes the

ground is the water, and the sky is a cliff.

In the morning, before setting out, I eat a bowl of oatmeal and write

my mother a quick note.

Have a lovely day with your conscience.

There's nothing unusual about this; my mother and I are regular

correspondents. Without knocking, I stride into the bathroom while

she is in the shower and smack the yellow legal pad against the

frosted glass so she can read it. I record her silence, the trickle of

water down the drain, and the squeaking of her feet, as a minor

victory.

When I roll my bike out of the garage, Dr. Vic sticks his head out

the window of his BMW and asks if I want a lift on his way to work.

"Sorry, but I don't take rides from strange men," I say. I usher my

mother's fiance on his way with a sweeping gesture.

Dr. Vic responds to my challenge with perfect, maddening

acquiescence:

he gives a pleasant nod, and simply coasts down the

driveway, when any normal person would slam on the gas and lay

down a patch of screw-you-kid rubber.

But I am feeling good as I pedal out onto Route 12, heading for the

tall white house on Dundee Avenue where my mother grew up and

Nana died. The wind and the summer smells of grass and tar make

me feel fast, and on that marker less stretch of road I can pretend I am

between almost any two places in the world. Leaving always gives

me a high feeling, and the bad

part

—

the coming

back

—

is a whole

day away. Route 12 dips and rises. I lean into a bend and the first

sign of town comes into view. The Beachcomber, a beleaguered

ranch motel, crouches across from the mouth of the interstate ramp,

catering to late-night drivers who are too tired to make it south to

Boston, or north to Bangor and Canada.

That's when I see

it

—see them.

I glance at the motel and there are

three men standing on the boardwalk in front of a room, loading the

trunk of a taxi. There is nothing distinct about these men: they are all

white; they all appear to be in the normal range of weight and build;

they are all dressed in suits and ties. In other words, they are three

men, three normal men, boarding a taxi. The taxi is a member of the

local fleet, a creaky-looking station wagon with plastic wood panels.

When the trio climbs in, I observe the undercarriage of the cab sag

slightly beneath their collective mass. Then I am around the corner

and turning into town.

I pass another block before I apprehend very clearly what it is

that was so striking about the three strangers: that is, the three

men weren't strangers at all. Those men were my mother's old

boyfriends. They were Paul and Dale and Jupps, all of them,

together. In another block, I work out the many reasons why this

is not possible, not the least of which happens to be that none of my

mother's boyfriends ever knew each other. Besides, Paul lives way up

north, and this is tourist season, his busy time, and as far as we know,

Jupps didn't even live in the United States anymore. On top of that,

the only time I could ever recall having seen any of them wearing a tie

was Dale at Nana's funeral, and that had been a bow tie.

No, of course not. Of course, I didn't see them.

What I saw didn't even qualify as a hallucination; it was too

boring. My vision was more like some kind of sad little kid wish,

like an imaginary friend, or your Real Father. Not the crazy drunk

that your mother's ex-boyfriend once had to beat the shit out of

with a snow shovel, not the jerk-off felon who never gave you

anything in your whole life except a polydactyl toe and a five-dollar

bill for your tenth

birthday

—

not him, not that

imposter

—

but your

Real Father,

the superhero. Your Real Father is sorry to have put

you through all this, but he couldn't risk it, because if his enemies

ever discovered his secret identity, his family would have been in

terrible danger. But now everything can be

different

—

because he

needs

your help—

and the invisible spy plane is idling in a grassy

field outside of town and it's go, go, go! The fate of the world may

depend on it!

In the time it takes to consider the matter logically and, in turn,

dust off the old (but not that old) Real Father Fantasy, I have traveled

another two blocks. I have also started to cry. I slam on the brakes

and start back to the motel, standing on the pedals and pushing

uphill. But the gravel parking lot is empty; the men and the taxi are

somewhere up the road, out of sight.

I am still sniffling when I reach my grandparents' house and find a

small gathering in the front yard. My grandfather and the neighbors,

Gil Desjardins and his wife, Mrs. Desjardins, stand before the 15

×

15-foot billboard that Papa has recently posted on the lawn, and

which lists, succinctly, his deeply felt political beliefs concerning the

most recent election, between Al Gore and George W. Bush.

I roll onto the grass and pull up beside them. Between their

shoulders I make out slashes of pink paint, and even before reading

the latest accusation, the situation is evident: for the third time in a

month, the vandal, the fascist paperboy, Steven Sugar, has attacked.

"Somehow," says Gil, "that the paint is pink, that makes it worse,

doesn't it?"

Mrs. Desjardins flicks away a pink chip with her fingernail. She

clucks sympathetically.

Papa crosses his arms and contemplates the pink message in

silence.

Mrs. Desjardins purses her lips at me and gives my bicep a squeeze.

She wears a kimono and a thin black ribbon fastened around her old

woman's neck. It is accepted that Gil's wife is odd.

"Whoever would have guessed a bourgeois newspaper could lead

to such a rumpus?." Her gaze falls on me expectantly.

I shrug.

"Oh, for skit's sake, Lana," says Gil.

"It is bourgeois. The

New York Times

is bourgeois."

"That may be, but if you say 'bourgeois,'you sound like an asshole.

In fact, I've been told that 'bourgeois' is a code word that assholes use

to recognize each other when they're in unfamiliar places. If you even

spell it in Scrabble, it makes you sound like an asshole."

"I believe you're being obtuse again, Gilbert," she says, not

sounding displeased.

At the center of the group, Papa has hardly shifted. I see now that

what the vandal has sprayed across the billboard this time is the

inexplicable

—

and yet, somehow, terribly

damning

—

epithet

COMMUNIST SHITHEEL.

Papa reaches out and uses his knuckle to

trace the letter

C.

The thin-lipped expression on his face is

unreadable.

"It's enough to make a person

think

—

"

he starts, and lets the

thought hang.

My grandfather gently moves his knuckle around the letter

O.

"Well, Henry, don't kill yourself. I'm going home to read the

dictionary and try to take a piss."

Gil starts scraping his walker back in the direction of his house.

When he reaches the edge of the driveway, he encounters some

difficulty in trying to jerk the legs over the lip of the pavement, and I

rush over to help. He throws his arm over my shoulder and I guide

the walker up onto the driveway.