What Hath God Wrought (5 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

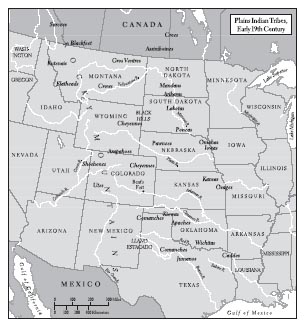

Many misconceptions regarding the American Indians of this period remain prevalent. Their societies were not static, necessarily fixed to particular homelands and lifestyles. They evolved and changed, often rapidly, sometimes as a result of deliberate decisions, both before and after their contact with whites. Native societies did not live in isolation until “discovered” by intruders; they traded with each other, exchanging not only goods but ideas and techniques as well. As early as the year 900, the cultivation of corn (maize) spread from Mexico to the inhabitants of what is now the eastern United States. “For hundreds of years,” notes the historian Colin Calloway, “Indian peoples explored, pioneered, settled, and shaped” their environment. Long before the Jacksonian Democrats conceived the program of “Indian Removal” from east of the Mississippi, tribes had migrated of their own volition. When the Native Americans first met whites, they integrated them into their existing patterns of trade and warfare, sometimes allying with them against historic enemies. They welcomed the trade goods on offer, especially those that made life easier like firearms, kettles, and metal tools.

17

Though their white contemporaries generally thought of them as hunters, the Native Americans were also experienced farmers. Throughout much of the United States they typically grew corn, squash, and beans together, cultivating them with a hoe. East of the Mississippi their crops provided more of their food than hunting and gathering did. Potatoes, tomatoes, and tobacco, indigenous American products eagerly taken up by Europeans, played a less important role in Native agriculture. In most tribes, farming was traditionally women’s work and hunting, men’s. Well-intentioned whites encouraged Indian men to downplay hunting, take up farming, and use plows pulled by draft animals. By 1815, white agricultural practices had been extensively adopted among several Amerindian nations east of the Mississippi; so had cattle-raising.

18

Some Native communities and individuals had become economically scarcely distinguishable from their white neighbors. On the other hand, the strong economic demand for deerskin and furs encouraged the Indians to pursue deer, beaver, and buffalo with renewed vigor rather than abandon the chase in favor of agriculture.

The numerous Native American nations were at least as diverse as the different European nations (linguistically, they were more diverse), and they adapted to contact with the Europeans in different ways, often quite resourceful. The Navajo transformed themselves from predatory nomads to sheepherders, weavers, and (later) silversmiths. Indians usually adopted aspects of Western culture that they found appealing and rejected others. Individuals did not always choose wisely: Exposed to alcohol, some became alcoholics. (Conversely, whites exposed to tobacco often became addicted to it.) Some Indians converted to Christianity, like the Mohican Hendrick Aupaumut, who preached pan-tribal unity and peaceful coexistence with the whites. Others undertook to revitalize their own religious traditions, as did the Seneca Handsome Lake and the Shawnee prophet Tenskwatawa, whose brother Tecumseh preached pan-tribal unity and militant resistance to the whites.

19

Despite the shocking fatalities from unfamiliar diseases, most Native peoples did not despair, nor (whatever whites might think) did they think of themselves as a doomed race. Their history is one of resilience and survival, as well as of retreat and death.

East of the Mississippi, the soggy, swampy Gulf region remained another multiethnic borderland (or “middle ground”), with Florida belonging to Spain, the white population of Louisiana still predominantly French and Spanish, and several powerful Indian nations asserting independence. The “Old Southwest” was a volatile area. Only gradually did it come under U.S. control. During the American War for Independence, the Spanish had allied with the rebels and conquered West and East Florida from the British. (West Florida extended along the Gulf Coast from what we call the Florida panhandle through what is now Alabama and Mississippi into Louisiana; the Apalachicola River divided the two Floridas from each other.) At the peace negotiations in 1783, Spain had been allowed to keep the Floridas as consolation for not having succeeded in capturing Gibraltar from the British. In 1810 and 1813, an ungrateful United States had unilaterally occupied chunks of West Florida. Policymakers in Washington had their eyes on East Florida as well.

The Native Americans of the Old Southwest had been caught in a time of turbulence by the coming of the Europeans. The indigenous Mississippian civilization had declined and left in its wake a variety of competing peoples somewhat analogous to the tribes that migrated around Europe following the disintegration of the Roman Empire. Those who called themselves the Muskogee played a pivotal role; whites named them the Creek Indians because they built their villages along streams. One branch of the Creeks had migrated southward into Florida, where they linked up with black “maroons” escaped from slavery and became known as Seminoles. The main body of Creeks, led by their chief Alexander McGillivray, had negotiated a treaty with George Washington’s administration guaranteeing their territorial integrity; they formed a national council and created a written legal code. But a civil war broke out among the Creeks in 1813, and the dissident “Red Stick” faction, who resented the influence of white ways, staged an ill-advised and bloody uprising against the Americans and their Native supporters.

20

Around the Great Lakes lay another historic “middle ground” where European empires and Native peoples had long competed with each other. In the eighteenth century, British, French, Americans, and the First Nations (as Canadians today appropriately call the Indian tribes) had all jockeyed for advantage in the rich fur trade and waged repeated wars on each other. Following independence, the Americans had nursed the delusion that Canadians would welcome them as liberators from the British. After two U.S. invasions of Canada, in 1776 and 1812, had both been repulsed, most Americans had given up this fantasy. The border between Canada and the United States began to take on a permanent character. Canada became a place of refuge for former American Loyalists who had experienced persecution in their previous homes and emphatically rejected U.S. identity. To the Catholic Quebecois, Yankee Protestants seemed even worse than British ones and the United States a de facto ally of the godless Napoleon.

By 1815, the land around the Great Lakes was losing its character as a “middle ground” where Native peoples could play off the competing white powers for their own advantage. The once-powerful Iroquois, a confederation of six nations, no longer found themselves in a position to carry out an independent foreign policy. When war came in 1812, the Iroquois north of the border supported their traditional ally, the British. Those to the south attempted neutrality but were compelled to fight for the United States against their kinsmen. The Canadian–U.S. border had taken on stability and real meaning. The Treaty of Ghent brought an end to sixty years of warfare over the Great Lakes region, going back to Braddock’s expedition of 1754.

21

Yet contemporaries did not know for sure that the wars were all over. They worried that the area might revert to instability and took precautions against this. In the 1830s, armed rebellions among both Anglophone and Francophone Canadians, coupled with friction between the United States and Britain, would confront American policymakers with that very real possibility.

White attitudes toward the Native Americans varied. Some viewed them as hostile savages needing to be removed or even exterminated. More sympathetic observers thought the Natives could and should convert to Christianity and adopt Western civilization. Whether they would then continue to exist as separate communities or be assimilated remained unclear; Washington’s administration had assumed the former, but Thomas Jefferson hoped for the latter.

22

Disagreement over “Indian policy” turned out to be an important issue separating the political parties that would emerge during the coming era. Despite all the mutual cultural borrowing between Native and Euro-Americans, neither cultural synthesis nor multicultural harmony achieved acceptance with the white public or government. Indians frequently intermarried with whites, as well as with blacks both enslaved and free, in all “middle ground” areas, and persons of mixed ancestry (sometimes called

métis

, a French term) like Alexander McGillivray often negotiated between their parental backgrounds. As time passed, however, such intermarriage became less acceptable in white society.

23

In the nineteenth century, two territorially contiguous empires expanded rapidly across vast continental distances: the United States and Russia. The tsarist empire was an absolute monarchy with an established church, yet in one respect surprisingly more tolerant than republican America. The Russians showed more willingness to accept and live with cultural diversity among their subject peoples.

24

II

The volcano of Tambora on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa erupted in a series of giant explosions commencing on April 7, 1815, and lasting five days. It was the largest volcanic eruption in recorded history, far surpassing that of Krakatoa in 1883 or Mount St. Helens in 1980. The volcano and the tsunami it generated killed some ten thousand people; many more died from indirect consequences. Gases emitted by Tambora included sulfur, which formed sulfuric acid droplets high in the atmosphere. For months, these droplets slowly girdled the Northern Hemisphere, absorbing and reflecting the sun’s radiation, lowering the surface temperature of the earth. Sunspot activity compounded the meteorological effects. By mid-1816, strange disturbances affected the weather and ocean currents in the North Atlantic. Snow fell in New England in June, July, and August; otherwise little precipitation appeared. South Carolina suffered a frost in mid-May. Widespread crop failures led to food shortages in many parts of North America and Europe. No one who lived through it would forget “the year without a summer.”

25

To people whose lives were governed by the sun—by the hours of daylight and the seasons of the year—the weather mattered a great deal. Even in the best of times life was hard in North America, the climate harsher than that of western Europe and West Africa, its temperatures extreme and storms violent. During what is called “the little ice age” of 1550 to 1850, the growing season shortened by a month, diminishing the size of harvests. A season of bad weather implied not only financial losses but hunger, cold, and curtailed communication. After the harrowing experiences of 1816, many Yankee farm families—particularly in northern New England—despaired of eking out a living where they were and moved west. Some speculated that the bizarre summer that year heralded the approach of Judgment Day and the millennium.

26

Agriculture provided the livelihood for the overwhelming majority of all Americans, regardless of race. Even people engaged in other occupations usually owned farmland as well. The clergyman had his glebe, the widowed landlady her garden. The village blacksmith supplemented his income with a plot of land. Geography as well as climate imposed constraints on people’s livelihoods. Much depended on access to navigable water. With it, one could market a crop nationally or internationally; without it, the difficulty of transporting bulky goods overland could limit one to a local market. Trying to find a product that would bear the cost of wagon transportation, many backcountry farmers hit upon distilling their grain into spirits. As a result, cheap whiskey flooded the country, worsening the problem of alcohol abuse that Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia had identified.

27

Life in America in 1815 was dirty, smelly, laborious, and uncomfortable. People spent most of their waking hours working, with scant opportunity for the development of individual talents and interests unrelated to farming. Cobbler-made shoes being expensive and uncomfortable, country people of ordinary means went barefoot much of the time. White people of both sexes wore heavy fabrics covering their bodies, even in the humid heat of summer, for they believed (correctly) sunshine bad for their skin. People usually owned few changes of clothes and stank of sweat. Only the most fastidious bathed as often as once a week. Since water had to be carried from a spring or well and heated in a kettle, people gave themselves sponge baths, using the washtub. Some bathed once a year, in the spring, but as late as 1832, a New England country doctor complained that four out of five of his patients did not bathe from one year to the next. When washing themselves, people usually only rinsed off, saving their harsh, homemade soap for cleaning clothes. Inns did not provide soap to travelers.

28

Having an outdoor privy signified a level of decency above those who simply relieved themselves in the woods or fields. Indoor light was scarce and precious; families made their own candles, smelly and smoky, from animal tallow. A single fireplace provided all the cooking and heating for a common household. During winter, everybody slept in the room with the fire, several in each bed. Privacy for married couples was a luxury.

29