What Hath God Wrought (52 page)

Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

While some of the whites placed in charge of the migration, particularly the career army officers, were honest and conscientious, others were political appointees out to get rich quick. The financial aspect of this first dispossession embarrassed the administration, for it cost over $5 million to expel the Choctaws—$2 million more than Jackson had claimed would suffice to deport

all

the tribes east of the Mississippi. The high cost reflected mismanagement and corruption, while the migrants themselves were frequently victims of parsimony.

73

Meanwhile, Jackson had been applying pressure to the rest of the tribes. Recognizing the missionaries as key adversaries, he withdrew federal funding from mission schools. The administration stopped making the promised annuity payments to the Cherokee Nation and put the money into escrow until the tribe should remove.

74

Existing treaties should have remained in force unless and until tribes consented to alter them, and even the Indian Removal Act as passed did not state otherwise.

75

But the president, far from defending existing U.S. treaty obligations, proved only too willing to turn over federal authority in the tribal lands to the states whenever they claimed it. With his encouragement, Alabama and Mississippi followed Georgia’s example and extended state jurisdiction over their own Native populations. And in February 1831, Jackson notified the Senate that he would no longer enforce the Indian Intercourse Act of 1802, a law protecting Indian lands against intruders. Thomas McKenney, the knowledgeable superintendent of Indian affairs, was a Calhoun protégé and holdover from the Monroe and Adams administrations who had become convinced that Removal was in the tribes’ best interests. But when he tried to carry out the policy with honesty and some consideration for Native rights, an impatient Jackson dismissed him in August, 1830.

76

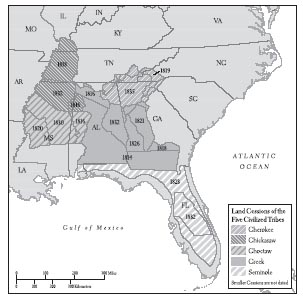

Adapted from Thomas Dionysius Clark and John D.W. Guice,

Frontiers in Conflict: The Old Southwest, 1975–1830

(University of New Mexico Press, 1989).

The Cherokees turned to the federal courts for protection. Georgia was clearly defying their rights as guaranteed by federal treaty, which according to the Constitution should be “the supreme law of the land.” Hiring two of the best constitutional lawyers in the country, John Sergeant and William Wirt (who had been attorney general under Monroe and Adams), the tribe brought a suit in the United States Supreme Court,

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

, to restrain the state from extending its authority over them. In March 1831, the justices voted 4 to 2 to sidestep the issue. Speaking for the majority, Chief Justice Marshall made clear his sympathy for the Indians’ case, but he held that the Cherokees constituted a “domestic dependent nation” and did not satisfy the definition of a sovereign “state” entitled to bring a suit over which the Supreme Court would have original jurisdiction.

77

The expression “domestic dependent nation” was destined to influence subsequent federal law on Indian tribes, but its first use enabled the Court to avoid an unwanted confrontation with state power and the executive branch. The Court may have been influenced by Jackson’s announcement the month before that he would not protect the Choctaws against the state of Mississippi in an analogous situation. Georgia served notice that it had extended its jurisdiction by trying and convicting in state court an Indian named Corn Tassel of the murder of another Indian in the Cherokee Nation. When the Supreme Court called for arguments on appeal, the state ignored the writ and executed the prisoner. Meanwhile, extreme state-righters introduced into Congress a bill to repeal section 25 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, the law authorizing the Supreme Court to hear appeals from state courts. Although defeated, the bill seems to have intimidated the Court, for it took no action on the contumacious behavior of the Georgia authorities.

78

A year later the Cherokee-Georgia crisis confronted the Supreme Court with another case, this time one the justices felt they had to address. Since Christian missionaries were among the most effective opponents of Removal, Governor George Gilmer of Georgia decided in January 1831 to expel them from the Cherokee lands.

79

Two of the missionaries, Samuel Worcester and Elizur Butler, refused to leave and were sentenced to four years at hard labor. Subjected to brutal treatment intended to crack their will to resist, while simultaneously offered pardons if they would acknowledge Georgia’s legal authority, the men courageously refused and appealed their convictions to the U.S. Supreme Court. The same lawyers who had appeared for the Cherokee Nation took their case, and by now both were leading political adversaries of Jackson, for in 1832 John Sergeant was vice-presidential candidate of the National Republicans and William Wirt presidential candidate of the Antimasonic Party. Georgia refused to acknowledge that the U.S. Supreme Court had jurisdiction. The state sent surveyors into the Cherokee Nation to prepare its lands for expropriation and tried to intimidate the missionaries’ wives and single white female schoolteachers into leaving. But these Christian women were made of stern stuff; they stuck to their posts and urged their men to continue defiance of the state.

80

In March 1832, when the two missionaries had endured eight months’ imprisonment, John Marshall delivered the opinion of the Court: The Cherokee Nation was protected by federal treaty within its own territory, “in which the law of Georgia can have no right to enter but with the assent of the Cherokees.” Georgia’s argument that the state possessed sovereignty over Indian lands by “right of discovery,” inherited from the British Crown (which the state had not deigned to present in person), was rejected. The act of Georgia under which the missionaries had been convicted and imprisoned was declared “void, as being repugnant to the constitution, treaties, and laws of the United States.” The decision represented the legal vindication of all the Cherokees had maintained.

81

Embarrassingly for Jackson, the nationalist former postmaster general John McLean, whom he had recently appointed to the Court, wrote a concurrence. The lone dissenter was Jackson’s other appointee, Henry Baldwin, who filed no opinion. The new justice feared doing so would only encourage Georgia to defy the Court, whose authority he respected even when he disagreed with it.

82

Everyone knew that enforcing the decision would not be easy.

Seeking the fundamental impulse behind Jacksonian Democracy, historians have variously pointed to free enterprise, manhood suffrage, the labor movement, and resistance to the market economy. But in its origins, Jacksonian Democracy (which contemporaries understood as a synonym for Jackson’s Democratic Party) was not primarily about any of these, though it came to intersect with all of them in due course. In the first place it was about the extension of white supremacy across the North American continent. By his policy of Indian Removal, Jackson confirmed his support in the cotton states outside South Carolina and fixed the character of his political party. Indian policy, not banking or the tariff, was the number one issue in the national press during the early years of Jackson’s presidency. But in his enthusiasm for Indian Removal, Jackson raised up an angry reaction, not only among evangelical Christians but also from constitutional nationalists, provoking them into an alliance with his political opponents that would shape party alignments for a generation. Claiming to be the champion of democracy, Jackson provoked opposition from the strongest nationwide democratic protest movement the country had yet witnessed. And a statistical analysis of congressional behavior has found that, as the second party system took shape, voting on Indian affairs proved to be the most consistent predictor of partisan affiliation.

83

IV

The Jacksonian leadership pushed Indian Removal through the House of Representatives with unseemly haste. On May 27, the day after the House voted, the president vetoed a major internal improvements measure, the Maysville Road Bill. The Maysville Road through Lexington, Kentucky, had been intended as a link in a nationwide transportation network, connecting the National Road to the north with the Natchez Trace to the south and the Ohio with the Tennessee river systems. Robert Hemphill of Pennsylvania, a Jackson supporter and proponent of internal improvements, having narrowly failed to win passage of a bill authorizing the entire road, had secured the Maysville segment as a more modest but promising start. Many such Jacksonian congressmen felt outraged that the president had pressured them to back Indian Removal, only to betray their interest in internal improvements. Some demanded a reconsideration of Indian Removal but found that the bill had reached the president’s desk and was beyond their recall. Now the significance of the deadline for passing Indian Removal became clear: The president could hold back his veto of the Maysville Road only ten days, and the White House realized that Indian Removal would lose if the veto message arrived on Capitol Hill before the vote.

84

Van Buren had urged the veto on the president. The Sly Fox of Kinderhook figured out that a stand against federal internal improvements would play well with state-rights Radicals in the South, thereby preventing Crawford’s old constituency from bolting to Calhoun. Furthermore, since New York already enjoyed the benefit of the Erie Canal, built with its own money, Van Buren’s home state stood to gain little from federally funded internal improvements elsewhere. Not that Jackson needed much persuasion: He was only too happy to veto a road that would pass through Henry Clay’s hometown. “I had the most amusing scenes in my endeavors to prevent him from avowing his intentions before the bill passed the two houses,” Van Buren confided to Francis Blair.

85

Working in secrecy, Jackson and Van Buren composed a veto message with the aid of James Knox Polk, a Tennessee Democrat, one of the few western congressmen suspicious of federal internal improvements.

The Maysville Veto Message attracted wide attention and remains a key document for understanding the subtleties of the Jacksonian attitude toward the transportation revolution. The message admitted that federal funding for national schemes of internal improvement had long been practiced, but also pointed out that constitutional doubt had never been altogether overcome and concluded that it would be safer to authorize it by a constitutional amendment. Pending the adoption of such an amendment, however, the president claimed to apply the test of whether the proposal was “general, not local, national, not State,” in character. Ignoring the fact that the Maysville Road would be a segment of an interstate highway system, Jackson declared that it failed this test. But while he criticized the Maysville Road for being insufficiently national, Jackson did not wish to be misunderstood as favoring federal funding for a more truly national transportation system. Instead, he warned that expenditures on internal improvements might jeopardize his goal of retiring the national debt—or, alternatively, require heavier taxes. Interestingly, Jackson did not set his face against economic development or the expansion of commerce in general. Far from decrying the effects of the transportation revolution, Jackson fully conceded the popularity and desirability of internal improvements. “I do not suppose there is an intelligent citizen who does not wish to see them flourish,” he assured his countrymen. But he felt that these projects were better left to private enterprise and the states. Analysis of the Maysville Veto Message and the evidence of Jackson’s economic policies in general do not sustain the claim made by some historians that he expressed resistance to market capitalism.

86

Politically, the Maysville Message was a masterstroke. Sure enough, Old Republicans welcomed the veto. “It fell upon the ears like the music of other days,” said John Randolph of Roanoke.

87

Yet it managed to avoid alienating the frontier. To their surprise, western Jacksonian congressmen who had voted in favor of the road, such as Thomas Hart Benton and Kentucky’s Richard Mentor Johnson, found the Old Hero’s popularity with their constituents undiminished. The Maysville Veto Message had been crafted to endorse what we would call the transportation revolution while condemning what we would call big government. Though the followers of Henry Clay declared this a contradiction in terms, there were plenty of westerners willing to take Old Hickory’s word for it that they could have both economic opportunity and republican simplicity. The message tended to firm up Jackson’s strength with his supporters while still further estranging his opponents. This comported well with Van Buren’s long-term objective, which (as he had explained to Thomas Ritchie in 1827) was to harden party lines.

88

Jackson vetoed several other internal improvements bills, in two cases exercising his “pocket veto” power over legislation passed in the last ten days of a congressional session. The pocket veto seemed high-handed to contemporaries; among Jackson’s predecessors, only Madison had used it.

89

Yet the president signed many other bills for aid to transportation and ended up spending twice as much money on internal improvements as all his predecessors combined, even when adjusted for inflation. Some of the projects he approved were built in territories rather than states, which made them constitutionally safer. Jackson’s administration showed more sympathy for improving natural waterways (used by cotton producers) than for canals (more often used by grain producers). Mixed public-private corporations in which the federal government owned some of the stock, a favorite method of subsidy during the Monroe and Adams administrations, found no favor under Jackson. On the other hand, the National, or Cumberland, Road, which had received appropriations of $1,668,000 from previous administrations, received $3,728,000 under Jackson’s—perhaps because it facilitated the settlement of the Old Northwest by Butternuts from the Upland South who voted Democratic. A Jacksonian Congress preserved state-rights principles by turning the completed sections of the National Road over to the states through which it passed.

90