What Stays in Vegas (21 page)

Read What Stays in Vegas Online

Authors: Adam Tanner

The security team quickly identified the first man from his loyalty card in a machine. In this case, they do not know if the drunk is a hotel guestâthus requiring a bit more delicate treatmentâor an outsider who should quickly be shown the door. Finally they ask the drunk man's companion, who appears far more soberâat least he's steady on his feetâfor a driver's license.

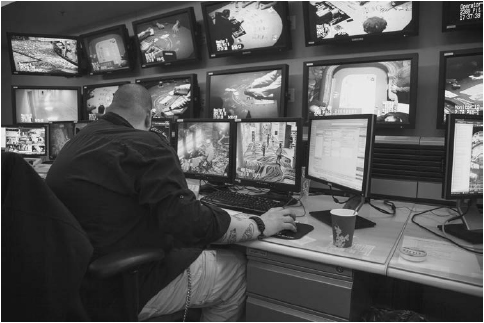

Security officer at work in a surveillance room at the ARIA Hotel in Las Vegas. Source: Author photo.

The List

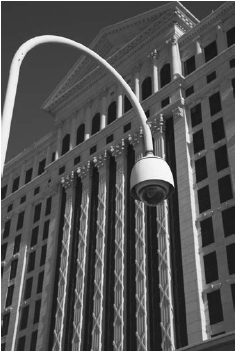

At casinos, surveillance starts from the moment one drives into or arrives at the property. On each level of the Caesars Palace parking lot cameras watch the passing vehicles, allowing license recognition technology to see if one has been reported stolen or is owned by somebody of interest.

1

Another camera behind a black dome of glass atop a pole shaped like an upside-down letter J looms above as people step out of their vehicles on the top floor. As they walk down several flights of stairs, yet another camera greets them at the bottom of every stairwell.

Toward the hotel's back entrance across another large open lot, a camera atop the building records arrivals. As people enter the elevator, digital video records the scene. Above the well-lit ground-floor hallway,

another camera captures the moment. Finally, at the turn into the actual casino, an especially large dome observes.

Surveillance camera overlooking the Caesars Palace parking lot. Source: Author photo.

An estimated three thousand cameras peer down on the action in a typical large casino,

2

more than in any other place in the United States.

3

They record the handbag left beside a slot machine and the smart phone misplaced on a bar counter after a flirtatious encounter. Tiny pinhole cameras mounted inside bars of the cashier's cage see who is redeeming chips. Bathrooms and guest rooms are free of surveillance, but floor and elevator cameras see who is coming and going. Electronic key readers record the exact time someone enters or exits a room and elevator cameras see arrivals on each floor. Cameras above gaming tables show enough detail to make out individual cards or a suspicious signal from players engaged in a con.

Public surveillance cameras have never appeared as omnipresent as they are today.

4

Although casinos pack in an especially concentrated number into their establishments, ever more sophisticated and affordable cameras watch us at every turn. Private businesses and government entities in the United States and abroad deploy them in growing numbers.

Cameras can record thousands of cars pulling into the lot every day and eighty thousand or so people milling around a casino. But without details on what they are seeing, such a vast amount of visual information is not tremendously useful. Security teams hope to link all these aspects of personal data togetherâso that they can use photo recognition technology to identify someone and then match him to a specific file of information.

Whatever device the security staff use, they need good information to ferret out cheats and swindlers. Before the days of sophisticated electronics, Las Vegas casinos relied on old-fashioned face books with profiles of potential troublemakers. The staff would page through a binder or folder stacked with the faces of individuals who might be a little dodgy. The most famous of these folders is the “black list,” officially known as the Excluded Person List of the Nevada Gaming Control Board.

5

This document lists people so undesirable that they should not be allowed even to set foot inside a casino, let alone gamble there. They are barred completely. Today, the list excludes thirty-three men and one woman for life from Nevada casinos. Some are former mobsters; others are habitual cheaters. Most are in their golden years.

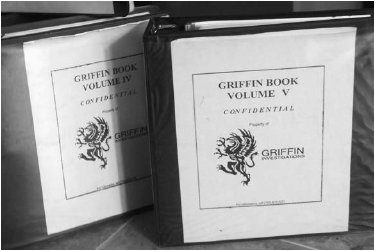

In 1967 Robert Griffin, a former Las Vegas police officer, and his wife, Beverly, started assembling a separate roster of slot machine cheaters, swindlers, thieves, and other undesirables casinos might want to exclude. Some on the Griffin list had not committed a crime but drew attention because of borderline illegal activities such as card counting, a skill that may prompt a casino to “trespass” or eject its practitioners. So-called advantage players became an ever bigger problem in the 1970s and 1980s. Griffin also offered casinos detective services to investigate such incidents.

Over the years the list grew into an essential reference book, and then a series of books with thousands of names. The Griffin Book included police mug shots, employee photographs, and any other images Robert and Beverly could obtain, plus basic characteristics of the people, such as height and weight and their suspected scam or talent that could put a casino at risk. The Griffin volumes achieved mythic status.

The Griffin Book. Source: Beverly Griffin (reprinted with permission).

William Hinkley worked his way up the ranks in casino security from a plainclothes investigator in the mid-1980s to top security official at a succession of popular hotels. He now oversees security at the Las Vegas Hooters Casino Hotel. For much of his career, the Griffin Book was important to his work. “Some people in the day interpreted Griffin as God,” he says. “In the 1980s if you were in the Griffin Book, it was almost like the black book.”

Griffin Investigations, the company Robert and Beverly founded in 1967, achieved its greatest success after its information helped uncover a group of blackjack card counters from MIT who had made millions in the 1990s, including from Caesars Palace. Their story later inspired the 2008 movie

21,

starring Kevin Spacey. Things came together in

the case after Griffin Investigations received a key tip. One of the card counters had a spat with the others and telephoned one of the Griffin investigators. The source revealed some of the blackjack counters were coming to town and alerted the investigator to the disguises they would wear. Those clues were enough to break the case. The MIT group had operated for so long because they represented a new kind of threat: brain power applied to card counting. “A lot of them were brilliant minds to whom this was a simple thing to do,” Griffin said. “And they differed from the old gamblers in that they were young Asians and young college students who had not before been a force in Las Vegas or other gaming areas.”

The publicity from the MIT case made Griffin a well-known adversary for card counters and cheats. How-to books and websites on card counting regularly referred to the Griffin Book, and memoirs by gamblers boasted of how they avoided ending up on the list or how they bested the company's scrutiny. Richard Marcus tells the world on his website that he is the “World's #1 Casino and Poker Cheating Expert.”

6

He portrays Griffin as a key adversary: “I myself was often under Griffin surveillance and spotted his agents staking out my Las Vegas house several times. Griffin and his detective agency were a major pain in my ass!”

Bob Nersesian, an attorney who defends gamblers accused of wrongdoing, also wrote about Griffin Investigations in his 2006 book

Beat the Players: Casinos, Cops and the Game Inside the Game

: “Amongst advantage and professional gamblers, few persons or companies are more vilified than Griffin Investigations. Simply, they are the bad guys. Griffin Investigations makes the lives of advantage gamblers miserable.” Beverly Griffin disagrees. She says she only gives casinos information. It's up to the casino to decide the gambler's fate.

In recent years Griffin's business has struggled. First of all, it ran into legal and financial troubles. Two gamblers detained at Caesars Palace and at the Imperial Palace based on information in the Griffin Book successfully sued in 2001.

7

Beverly Griffin remains bitter that her company ended up in court and was compelled to pay $300,000 in legal fees. Griffin filed for

Chapter 11

bankruptcy protection in 2005,

the same year Harrah's bought Caesars Palace. She owed more than $100,000 to her lawyer and more than $100,000 to those who sued her, according to court papers.

The other challenge to the dominance of the Griffin Book has come from the explosion of information in the Internet age. Technology allows casinos to identify undesirables more easily than in the past. Many rely on their own databases rather than the Griffin Book. Caesars Entertainment and MGM Resortsâwhich together own a large chunk of the Las Vegas Stripâno longer subscribe, although some other casinos do.

8

Griffin says she still has many clients among casinos worldwide because it is harder for regional establishments to recognize cheaters and advantage players from Las Vegas or elsewhere. The worst may have passed for Beverly Griffin. Now divorced, she runs the business without her retired husband. She says she has paid off her debts after five years. Her service has moved to the Internet, and on the advice of her attorney, she has revamped its database to sharpen its accuracy. The problem in the past, she says, was that the Griffin Book might deem someone a cheater even if he had never been convicted of a crime. Today, her seven thousand listings are more cautious in terms of what they allege.

The threat of litigation has made security teams across the industry more cautious. In the days of mob influence in Las Vegas, security officials might have taken a suspected cheater or card counter to a back room to mete out a warning on the spot. It seems obligatory for films about Las Vegas to re-create such scenes. Griffin says such frontier justice ended in the 1970s. Nowadays, multimillion-dollar casinos would not risk losing their license to beat up a card counter.

With corporations trying to maintain a good public image, security officials do all they can to avoid lawsuits. They do not even like to accuse someone of counting cards. Likewise, security and surveillance officials are more reserved about swapping information with other casinos. They don't want to face lawsuits because of information they shared about a gambler. So even if there is more information readily available than in the past, the threat of litigation has tempered its distribution.

Video Recognition

In recent years, some casinos and other businesses have begun linking video recognition technology to their surveillance systems. Sure, a good surveillance officer can spot patterns of suspicious behavior and known troublemakers. Some remember faces from months or even years before. Yet with newcomers showing up every day, they cannot know the background of the overwhelming majority of the people on the casino floor. In the future, technologists hope, photo recognition will easily and accurately connect faces engaged in suspicious behavior with the names and files of those who have committed previous offenses.

Some security veterans look with awe at how such software has the potential to make their jobs ever easier. Yet in truth, the technology is still far from an all-knowing Big Brother. One leading company that sells photo recognition and security management software to casinos is called iView Systems. James Moore, the Canadian company's vice president, says facial identification correctly identifies 60â80 percent of people of interest to casino security teams. The problem remains a high rate of false positivesâinstances when the system thinks it recognizes a suspicious person but is, in fact, mistaken.