What Technology Wants (51 page)

Read What Technology Wants Online

Authors: Kevin Kelly

However, if we fail to enlarge the possibilities for other people, we diminish them, and that is unforgivable. Enlarging the scope of creativity for others, then, is an obligation. We enlarge others by enlarging the possibilities of the techniumâby developing more technology and more convivial expressions of it.

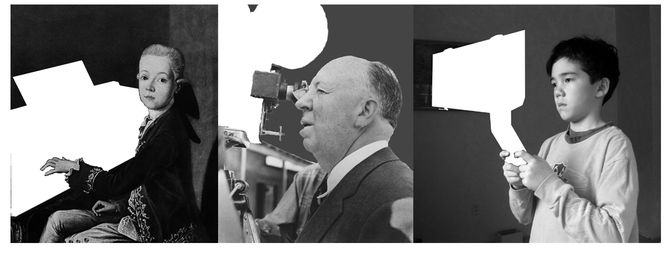

If the best cathedral builder who ever lived was born now, instead of 1,000 years ago, he would still find a few cathedrals being built to spotlight his glory. Sonnets are still being written and manuscripts still being illuminated. But can you imagine how poor our world would be if Bach had been born 1,000 years before the Flemish invented the technology of the harpsichord? Or if Mozart had preceded the technologies of piano and symphony? How vacant our collective imaginations would be if Vincent van Gogh had arrived 5,000 years before we invented cheap oil paint? What kind of modern world would we have if Edison, Greene, and Dickson had not developed cinematic technology before Hitchcock or Charlie Chaplin grew up?

Missing Technologies.

The boy Mozart before the piano was invented, Alfred Hitchcock before movie cameras, and my son Tywen before the next big thing.

The boy Mozart before the piano was invented, Alfred Hitchcock before movie cameras, and my son Tywen before the next big thing.

How many geniuses at the level of Bach and Van Gogh died before the needed technologies were available for their talents to take root? How many people will die without ever having encountered the technological possibilities that they would have excelled in? I have three children, and though we shower them with opportunities, their ultimate potential may be thwarted because the ideal technology for their talents has yet to be invented. There is a genius alive today, some Shakespeare of our time, whose masterworks society will never own because she was born before the technology (holodeck, wormhole, telepathy, magic pen) of her greatness was invented. Without these manufactured possibilities, she is diminished, and by extension all of us are diminished.

For most of history, the unique mix of talents, skills, insights, and experiences of each person had no outlet. If your dad was a baker, you were a baker. As technology expands the possibility of space, it expands the chance that someone can find an outlet for their personal traits. We thus have a moral obligation to increase the best of technology. When we enlarge the variety and reach of technology, we increase options not just for ourselves and not just for others living but for all those to come as the technium ratchets up complexity and beauty over generations.

A world with more opportunities produces more people capable of producing yet more opportunities. That's the strange loop of bootstrapping creation, which constantly makes offspring superior to itself. Every tool in the hand presents civilization (all those alive) with another way of thinking about something, another view of life, another choice. Every idea that is made real (technology) enlarges the space we have to construct our lives. The simple invention of a wheel unleashed a hundred new ideas of what to do with it. From it issued carts, pottery wheels, prayer wheels, and gears. These in turn inspired and enabled millions of creative people to unleash yet more ideas. And many people along the way found their story through these tools.

This is what the technium is. The technium is the accumulation of stuff, of lore, of practices, of traditions, and of choices that allow an individual human to generate and participate in a greater number of ideas. Civilization, starting from the earliest river valley settlements 8,000 years ago, can be considered a process by which possibilities and opportunities for the next generation are accumulated over time. The average middle-class person today working as a retail sales clerk has inherited far more choices than a king of old, just as the ancient king inherited more options than a subsistence nomad had before him.

While we amass possibilities, we do so because the very cosmos itself is on a similar expansion. As far as we can tell, the universe began as an undifferentiated point and steadily unfolded into the detailed nuancs that we call matter and reality. Over billions of years, cosmic processes created the elements, the elements birthed molecules, the molecules assembled into galaxiesâeach widening the realm of the possible.

The journey from nothing to the plentitudes of a materializing universe can be reckoned as the expansion of freedoms, choices, and manifest possibilities. In the beginning there was no choice, no free will, no thing but nothing. From the big bang onward, the possible ways matter and energy could be arranged increased, and eventually, through life, the freedom of possible actions increased. With the coming of imaginative minds, even possible possibilities increased. It is almost as if the universe was a choice assembling itself.

In general, the long-term bias of technology is to increase the diversity of artifacts, methods, and techniques of creating choices. Evolution aims to keep the game of possibilities going.

I began this book with a quest for a method, an understanding at least, that would guide my choices in the technium. I needed a bigger view to enable me to choose technologies that would bless me with greater benefits and fewer demands. What I was really searching for was a way to reconcile the technium's selfish nature, which wants more of itself, with its generous nature, which wants to help us to find more of ourselves. Looking at the world through the eyes of the technium, I've grown to appreciate the unbelievable levels of selfish autonomy it possesses. Its internal momentum and directions are deeper than I originally suspected. At the same time, seeing the world from the technium's point of view has increased my admiration for its transformative positive powers. Yes, technology is acquiring its own autonomy and will increasingly maximize its own agenda, but this agenda includesâas its foremost consequenceâmaximizing possibilities for us.

I've come to the conclusion that this dilemma between these two faces of technology is unavoidable. As long as the technium exists (and it must exist if we are), then this tension between its gifts and its demands will continue to haunt us. In 3,000 years, when everyone finally gets their jet packs and flying cars, we will still struggle with this inherent conflict between the technium's own increase and ours. This enduring tension is yet another aspect of technology we have to accept.

As a practical matter I've learned to seek the minimum amount of technology for myself that will create the maximum amount of choices for myself and others. The cybernetician Heinz von Foerster called this approach the Ethical Imperative, and he put it this way: “Always act to increase the number of choices.” The way we can use technologies to increase choices for others is by encouraging science, innovation, education, literacies, and pluralism. In my own experience this principle has never failed: In any game, increase your options.

Â

Â

Â

There are two kinds of games in the universe: finite games and infinite games. A finite game is played to win. Card games, poker rounds, games of chance, bets, sports such as football, board games such as Monopoly, races, marathons, puzzles, Tetris, Rubik's Cube, Scrabble, sudoku, online games such as

World of Warcraft,

and

Halo

âall are finite games. The game ends when someone wins.

World of Warcraft,

and

Halo

âall are finite games. The game ends when someone wins.

An infinite game, on the other hand, is played to keep the game going. It does not terminate because there is no winner.

Finite games require rules that remain constant. The game fails if the rules change during the game. Altering rules during play is unforgivable, the very definition of unfairness. Great effort, then, is taken in a finite game to spell out the rules beforehand and enforce them during the game.

An infinite game, however, can keep going only by changing its rules. To maintain open-endedness, the game must play with its rules.

A finite game such as baseball or chess or Super Mario must have boundariesâspatial, temporal, or behavioral. So big, this long, do or don't do that.

An infinite game has no boundaries. James Carse, the theologian who developed these ideas in his brilliant treatise

Finite and Infinite Games,

says, “Finite players play within boundaries; infinite players play with boundaries.”

Finite and Infinite Games,

says, “Finite players play within boundaries; infinite players play with boundaries.”

Evolution, life, mind, and the technium are infinite games. Their game is to keep the game going. To keep all participants playing as long as possible. They do that, as all infinite games do, by playing around with the rules of play. The evolution of evolution is just that kind of play.

Unreformed weapon technologies generate finite games. They produce winners (and losers) and cut off options. Finite games are dramatic; think sports and war. We can think of hundreds of more exciting stories about two guys fighting than we can about two guys at peace. But the problem with those exciting 100 stories about two guys fighting is that they all lead to the same endâthe demise of one or both of themâunless at some point they turn and cooperate. However, the one boring story about peace has no end. It can lead to a thousand unexpected storiesâmaybe the two guys become partners and build a new town or discover a new element or write an amazing opera. They create something that will become a platform for future stories. They are playing an infinite game. Peace is summoned all over the world because it births increasing opportunities and, unlike a finite game, contains infinite potential.

The things in life we love mostâincluding life itselfâare infinite games. When we play the game of life, or the game of the technium, goals are not fixed, the rules are unknown and shifting. How do we proceed? A good choice is to increase choices. As individuals and as a society we can invent methods that will generate as many new

good

possibilities as possible. A good possibility is one that will generate more good possibilities . . . and so on in the paradoxical infinite game. The best “open-ended” choice is one that leads to the most subsequent “open-ended” choices. That recursive tree is the infinite game of technology.

good

possibilities as possible. A good possibility is one that will generate more good possibilities . . . and so on in the paradoxical infinite game. The best “open-ended” choice is one that leads to the most subsequent “open-ended” choices. That recursive tree is the infinite game of technology.

The goal of the infinite game is to keep playingâto explore every way to play the game, to include all games, all possible players, to widen what is meant by playing, to spend all, to hoard nothing, to seed the universe with improbable plays, and if possible to surpass everything that has come before.

In his mythic book

The Singularity Is Near,

Ray Kurzweil, serial inventor, technology enthusiast, and unabashed atheist, announces: “Evolution moves toward greater complexity, greater elegance, greater knowledge, greater intelligence, greater beauty, greater creativity, and greater levels of subtle attributes such as love. In every monotheistic tradition God is likewise described as all of these qualities, only without limitation. . . . So evolution moves inexorably toward this conception of God, although never quite reaching this ideal.”

The Singularity Is Near,

Ray Kurzweil, serial inventor, technology enthusiast, and unabashed atheist, announces: “Evolution moves toward greater complexity, greater elegance, greater knowledge, greater intelligence, greater beauty, greater creativity, and greater levels of subtle attributes such as love. In every monotheistic tradition God is likewise described as all of these qualities, only without limitation. . . . So evolution moves inexorably toward this conception of God, although never quite reaching this ideal.”

If there is a God, the arc of the technium is aimed right at him. I'll retell the Great Story of this arc again, one last time in summary, because it points way beyond us.

As the undifferentiated energy at the big bang is cooled by the expanding space of the universe, it coalesces into measurable entities, and, over time, the particles condense into atoms. Further expansion and cooling allows complex molecules to form, which self-assemble into self-reproducing entities. With each tick of the clock, increasing complexity is added to these embryonic organisms, increasing the speed at which they change. As evolution evolves, it keeps piling on different ways to adapt and learn until eventually the minds of animals are caught in self-awareness. This self-awareness thinks up more minds, and together a universe of minds transcends all previous limits. The destiny of this collective mind is to expand imagination in all directions until it is no longer solitary but reflects the infinite.

There is even a modern theology that postulates that God, too, changes. Without splitting too many theological hairs, this theory, called Process Theology, describes God as a process, a perfect process, if you will. In this theology, God is less a remote, monumental, gray-bearded hacker genius and more of an ever-present flux, a movement, a process, a primary self-made becoming. The ongoing self-organized mutability of life, evolution, mind, and the technium is a reflection of God's becoming. God-as-Verb unleashes a set of rules that unfold into an infinite game, a game that continually loops back into itself.

I bring up God here at the end because it seems unfair to speak about autocreation without mentioning Godâthe paragon of autocreation. The only other alternative to an endless string of creations triggered by previous creation is a creation that emerges from its own self-causation. That prime self-causation, which is not preceded but instead first makes itself before it makes either time or nothingness, is the most logical definition of God. This view of a mutable God does not escape the paradoxes of self-creation that infect all levels of self-organization, but rather it embraces them as necessary paradoxes. God or not, self-creation is a mystery.

In one sense, this is a book about continuous autocreation (with or without the concept of a prime autocreation). The tale told here tells how the ratcheting bootstrapping of increasing complexity, expanding possibilities, and spreading sentienceâwhich we now see in the technium and beyondâis driven by forces that were inherent within the first nanospeck of existence and how this seed of flux has unfolded itself in such a manner that it can, in theory, keep unfolding and making itself for a very long time.

Other books

Bad In Boots 02 - Ty's Temptation by Patrice Michelle

The Masked Truth by Kelley Armstrong

An Heir of Uncertainty by Everett, Alyssa

The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst by Whyte, Kenneth

Through the Veil by Lacey Thorn

The Age of Cities by Brett Josef Grubisic

Eye of the Beholder by Emma Jay

Desperate and Daring 02 - Belle of the Ball by Ella J. Quince

The Piper's Tune by Jessica Stirling

Jane's Harmony (Jane's Melody #2) by Ryan Winfield