What You Can Change . . . And What You Can't*: The Complete Guide to Successful Self-Improvement (10 page)

Authors: Martin E. Seligman

Tags: #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Happiness

Some of our everyday anxiety, depression, and anger go beyond their useful function. Most adaptive traits fall along a normal spectrum of distribution, and the capacity for bad weather inside for everyone some of the time means that some of us will have terrible weather all of the time. In general, when the hurt is pointless and recurrent—when, for example, anxiety insists we formulate a plan but no plan will work—it is time to take action to relieve the hurt. There are three hallmarks indicating that anxiety has become a burden that wants relieving:

First, is it

irrational?

We must calibrate our bad weather inside against the real weather outside. Is what you are anxious about out of proportion to the reality of the danger? For some of you, living in the shadow of terminal illness, violence, unemployment, or poverty, anxiety is often founded in reality. But for most of you, daily anxiety may be a vestige of a geological epoch you are no longer living in.

Is your anxiety out of proportion to the reality of the danger you fear? Here are some examples that may help you answer this question. All of the following are

not

irrational:

A fire fighter trying to smother a raging oil well burning in Kuwait repeatedly wakes up at four in the morning because of flaming terror dreams.

A mother of three smells perfume on her husband’s shirts and, consumed by jealousy, broods about his infidelity, reviewing the list of possible women over and over.

A woman is the sole source of support for her children. Her co-workers start getting pink slips. She has a panic attack.

A student who has failed two of his midterm exams finds, as finals approach, that he can’t get to sleep for worrying. He has diarrhea most of the time.

The only good thing that can be said about your fears is that they are well-founded.

In contrast, all of the following are irrational, out of proportion to the danger:

An elderly man, having been in a fender bender, broods about travel and will no longer take cars, trains, or airplanes.

An eight-year-old child, his parents having been through an ugly divorce, wets his pants at night. He is haunted with visions of his bedroom ceiling collapsing on him.

A college student skips her final exam because she fears that the professor will look at her while she is writing and her hand will then shake uncontrollably.

A housewife, who has an MBA and who accumulated a decade of experience as a financial vice president before her twins were born, is sure her job search will be fruitless. She delays preparing her resume for a month.

The second hallmark of anxiety out of control is

paralysis

. Anxiety intends action: Plan, rehearse, look into shadows for lurking dangers, change your life. When anxiety becomes strong, it is unproductive; no problem-solving occurs. And when anxiety is extreme, it paralyzes you. Has your anxiety crossed this line? Some examples:

A woman finds herself housebound because she fears that if she goes out, she will be bitten by a cat.

Consumed by the fear that his girlfriend is unfaithful, a young swain never calls her again.

A salesman broods about the next customer hanging up on him and makes no more cold calls.

A fourth-grader is often chosen last for teams and refuses to go to school anymore because “everybody hates me.”

A writer, afraid of the next rejection slip, stops writing.

The final hallmark is

intensity

. Is your life dominated by anxiety? Dr. Charles Spielberger, a past president of the American Psychological Association, is also one of the world’s foremost testers of emotion. He has developed well-validated scales for calibrating how severe anxiety and anger are. He divides these emotions into their

state

form (“How are you feeling right now?”) and their

trait

form (“How do you generally feel?”). Since our interest is change in personality, with Dr. Spielberger’s kind permission I will use his trait questions.

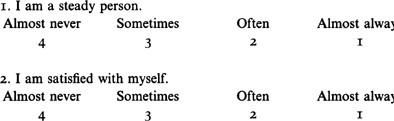

SELF-ANALYSIS QUESTIONNAIRE

3

Read each statement and then mark the appropriate number to indicate

how you generally feel

. There are no right or wrong answers. Do not spend too much time on any one statement, but give the answer that seems to describe how you

generally

feel.

Scoring

. Simply add up the numbers under your answers to the ten questions. Be careful to notice that some of the rows of numbers go up and others go down. The higher your total, the more the trait of anxiety dominates your life. Adult men and women have slightly different scores on average, with women being somewhat more anxious generally.

If you scored 10–11, you are in the lowest 10 percent of anxiety.

If you scored 13–14, you are in the lowest quarter.

If you scored 16–17, your anxiety level is about average.

If you scored 19–20, your anxiety level is around the seventy-fifth percentile.

If you scored 22–24 and you are male, your anxiety level is around the ninetieth percentile.

If you scored 24–26 and you are female, your anxiety level is around the ninetieth percentile.

If you scored 25 and you are male, your anxiety level is at the ninety-fifth percentile.

If you scored 27 and you are female, your anxiety level is at the ninety-fifth percentile.

T

HE AIM

of this section is to help you decide if you should try to change your general anxiety level. There are no hard-and-fast rules, but to make this decision, you should take all three hallmarks—irrationality, paralysis, and intensity—into account. Here are my rules of thumb:

If your score is at the ninetieth percentile or above, you can probably improve the quality of your life by lowering your general anxiety level—regardless of paralysis and irrationality.

If your score is at the seventy-fifth percentile or above, and you feel that anxiety is either paralyzing you or that it is unfounded, you should probably try to lower your general anxiety level.

If your score is 18 or above, and you feel that anxiety is both paralyzing you and that it is unfounded, you should probably try to lower your general anxiety level.

Lowering Your Everyday Anxiety

Everyday anxiety level is not a category to which psychologists have devoted a great deal of attention. The vast bulk of work on emotion is about “disorders”—helping “abnormal” people to lead “normal” emotional lives. In my view, not nearly enough serious science has been done to improve the emotional life of normal people—to help them lead better emotional lives. This task has been left by default to preachers, profiteers, advice columnists, and charismatic hucksters on talk shows. This is a gross mistake, and I believe that one of the obligations of qualified psychologists is to help members of the general public try to make rational decisions about improving their emotional lives. Enough research has been done, however, for me to recommend two techniques that quite reliably lower everyday anxiety levels. Both techniques are cumulative, rather than one-shot fixes. They require twenty to forty minutes a day of your valuable time.

The first is

progressive relaxation

, done once or, better, twice a day for at least ten minutes. In this technique, you tighten and then turn off each of the major muscle groups of your body, until you are wholly flaccid. It is not easy to be highly anxious when your body feels like Jell-O. More formally, relaxation engages a response system that competes with anxious arousal. If this technique appeals to you, I recommend Dr. Herbert Benson’s book

The Relaxation Response

.

4

The second technique is regular

meditation

. Transcendental meditation (TM) is one useful, widely available version of this. You can ignore the cosmology in which it is packaged if you wish, and treat it simply as the beneficial technique it is. Twice a day for twenty minutes, in a quiet setting, you close your eyes and repeat a

mantra

(a syllable whose “sonic properties are known”) to yourself. Meditation works by blocking thoughts that produce anxiety. It complements relaxation, which blocks the motor components of anxiety but leaves the anxious thoughts untouched. Done regularly, meditation usually induces a peaceful state of mind. Anxiety at other times of the day wanes, and hyperarousal from bad events is dampened. Done religiously, TM probably works better than relaxation alone.

5

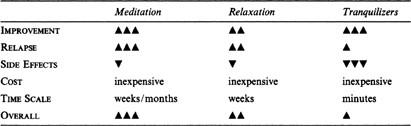

There also exists a quick fix. The minor tranquilizers—Valium, Dalmane, Librium, and their cousins—relieve everyday anxiety. So does alcohol. The advantage of all these is that they work within minutes and require no discipline to use. Their disadvantages outweigh their advantages, however. The minor tranquilizers make you fuzzy and somewhat uncoordinated as they work (a not uncommon side effect is an automobile accident). Tranquilizers soon lose their effect when taken regularly, and they are habit-forming—probably addictive. The same is true of alcohol, and it is even more clearly addictive. Alcohol, in addition, produces gross cognitive and motor disability in lockstep with its anxiety relief. When taken regularly over long periods, deadly liver and brain damage ensue.

I am, incidentally, no puritan about drugs or about quick fixes, so when I advise you against their use—as I do here—it is not out of priggishness. If you crave quick and temporary relief from acute anxiety, either alcohol or minor tranquilizers, taken in small amounts and only occasionally, will do the job. They are, however, a distant second-best to progressive relaxation and meditation, which are each worth trying before you seek out psychotherapy or in conjunction with therapy. Unlike tranquilizers and alcohol, neither of these techniques is likely to do you any harm.

6

The Right Treatment

ANXIETY SUMMARY TABLE

*