Wheel of Stars (6 page)

Authors: Andre Norton

The dark fell away—not being lifted or dispersed evenly, but as if rents slit in a bag, tore

and twisted to give her freedom. There was no night now. Rather light was all about her. She crouched on the ground, her shoulders against solid rock and before her stretched a countryside—no field or meadow of her own knowing—another place.

She cried out, flinging up one arm to hide her eyes. What had happened back at the standing stones she knew? Had she fallen, been injured so that what she saw now was hallucination? Only it was unchanging. Instead of any sun there was a green glow. The watch which she held in her other hand warmed a little more. There was security somehow in the touch of it—as if the medallion were an anchor holding her to a point of precarious safety. She fought a small battle with her fear and lowered her arm, forcing herself to look about.

Before and below her stretched open land—though, as she turned her head slowly, first right and then left—she sighted a dense shadow which she believed marked a forest, taller, thicker, more of a barrier than any wood she knew. The open land possessed a covering of short, thick vegetation akin to moss. That was broken here and there by circular patches of what appeared either to be bare sand of a dull golden color, or others formed of low-growing, profusely blooming flowers, a grey-white in color.

There was something odd about those patches. The ones formed of sand appeared, in a way, wholesome, attractive while the flowers repelled. Gwennan lifted her head higher to view the sky. There was no sign of any sun—no source for the

green light. Only when she looked earthward again, she believed she could detect shimmering flecks of gold above the sand, wan wisps of leaden-grey over the flowers.

Nothing moved, there was no wind. The far reaches where stood the forest, dark walls betrayed no trembling leaf, no sway of branch. It was as if this was a painted landscape, set in place as one might lower the backdrop of a theater’s stage.

Gwennan had somehow lost all surprise; her bewilderment was blunted. Holding the pendant had given her respite from fear. Instead curiosity began to stir. Though as yet she had no intention of venturing from her place by the rocks. Now she slipped her hand along that nearest one, proving by its rough touch that more than one of her senses testified that she was really here.

No wind—no sound—

Then—breaking the silence as a tap might shatter a thin panel of glass, there came the trill of a high-noted horn. Gwennan’s head swung right. Movement at last in that wall of the wood. From its verge streaked light shapes, skimming close to the ground. As they came they gave tongue, belling like hounds hot on the scent of a quarry they coursed, one which they were fast running to bay. She could see them cross the golden sand, but they leapt high to avoid those patches where grew the flowers. They were no hounds of earth. Their coats were largely white but they were marked on feet, tails, and ears with gold. While their eyes glowed brilliant green—too large in size to match their long, narrow heads.

Again the horn sounded. Now, out of the woods, came, at a steady canter, a huge deer—or was it a deer? Gwennan could only apply the terms she knew and that did not quite fit. The creature was as large as any horse, and its branched antlers were also golden, as were its hooves. On its back was a rider, though there was no saddle nor bridle.

A woman rode so. Her golden hair was fastened at the nape of her neck, but its long strands blew forward and about her as if she had brought with her some tamed breeze of her own as a servant. She was dressed in breeches of a color both blue and green, shifting from shade to shade as might the waves of the sea. A jerkin of the same color left her arms bare to the shoulders save for broad wristlets of green-gemmed gold which extended well up her forearms. One of her hands cradled the curved horn, and in the other she carried a short spear of gold, the point of which gave off flashing light.

As she drew nearer, following the questing pack of her hounds, her head was held high and Gwennan could see her features clearly. The girl shivered. This was not her world—yet there rode Lady Lyle—or a younger copy of her, the years banished and strength and beauty fully hers once more.

The deer came to a halt, but it seemed restive, moving its feet from side to side, raising its hooves, to replace them with an impatient stamp, while the hounds, as they drew level with the higher spur of ground where Gwennan still knelt by the stone, appeared to have lost whatever trail they had been coursing. They scattered, questing

here and there, sniffing warily a goodly distance from each clump of flowers, giving tongue, when near those, to low growls.

None of the pack appeared to notice nor scent Gwennan, for which she was thankful. Nor did the woman look in her direction. Rather she stared at that arm of the wood which lay to the left, as if she expected something or someone to soon emerge from that direction.

There sounded no peal of horn—rather a brazen bellow, harsh, grating on the ear. The hounds pulled together into a pack, fell back to surround the rider and her beast. She slung her horn by its golden cord across her shoulder, took the spear, which looked to Gwennan to be too small and frail to be of much use, in both hands.

The girl stared toward that other strip of woods. Again movement among the outer run of trees. What padded out of that shadow were no clean-limbed hounds. Rather there shambled from concealment under the low branched trees humped figures, shuffling yet covering the ground with deceptive speed. Some stood or moved on two legs as if humanoid, several padded on four paws. All were the misshapen things of men’s darkest nightmares. There was a thing with wings and an owl-like head. Yet, though the wings quivered ceaselessly, it did not take to the air—perhaps those wings could not support it there.

Another was a stumbling caricature of a man, its body completely haired. It swung heavy arms which ended in hands equipped with long curved claws. A third ran four-footed. Its forequarters

were those of a wolf-like beast, the bare hind legs were human, and it possessed no tail. There were others—all grotesque, twisted. From some Gwennan quickly looked away, feeling a little sick.

They, too, had their master and he was also mounted. A huge reptilian thing slithered in the wake of that pack. Its scaled back was fringed with upstanding plates of bone. Between two of the largest of those a man balanced. His head was also bare, and those tight curls of golden hair were as familiar to Gwennan as the other rider’s features had been—he wore Tor’s face.

Like the woman, he was dressed in breeches, boots and jerkin, but his were of ashen grey, much akin to the shadowy color of his beast’s hide. And he carried, balanced across his thighs, a black rod which lacked any point, yet still must be, Gwennan guessed, a weapon.

The monster band loped or shuffled on, coming to a halt still some distance from the woman and her hounds. Thus the two parties confronted each other. There was no speech, both hounds and monsters were also utterly silent now—though they eyed each other with a hot hatred plain to read in every line of their tense bodies.

Were the two riders communicating in some wordless fashion? Gwennan thought that perhaps they were. This was, without a doubt, the meeting of long-time enemies, yet it seemed they were not about to openly enter into battle.

She shifted her own weight a fraction and—

In her hand the pendant seemed to move, pushing against her palm. Its once-gentle warmth became a blazing coal. She was startled, not only into a low cry of pain, but into dropping it to swing at the end of its chain. The dialed face was up, the symbols on it afire. She was sure her fingers had been seared—still there were no burn marks on her flesh.

That cry, short and low as it had been, drew the attention of those two below. Their heads turned sharply, their eyes sought her. She felt rather than saw their mutual surprise, for their features remained nearly expressionless. Now the deer and the dragon thing turned, pacing evenly in line but well apart, bringing the riders to her hillock. Gwennan pulled herself up to stand. She could not guess what form of danger she was about to face, but she had pride enough to determine not to meet it on her knees—as if she were some frightened animal pursued to eventual extinction.

Tor—Lady Lyle—she could only see them so in spite of their strange dress and the weird companies they now headed. Their brilliant eyes rested on her and she thought she saw something other than just a faint shade of what might be recognition. It was the lady who spoke first.

“Farfarer—you are welcome for what you bring—”

He who was Tor laughed. “That is the full truth, kinswoman. Only do you think to snare this other to your aid in our battle? I believe you have built too high on far too little. None of the others can now come to your calling—no matter how sweetly rings that horn of yours. Is that not so, outworlder?”

Now he demanded an answer from Gwennan.

“My blood kin here believes that you will serve as a battlemaid in her train. I do not doubt that she has schemed mightily towards that end. But what has our war to do with you? You are one of the others — the short-lived — the unmemoried. Nothing lies in this world for you except—”

He snapped his fingers and the creature with the owl head turned that fully towards the girl, showing red pits of fire where its eyes might rightfully be set.

“Except perhaps a closer meeting with such as this one, my faithful and obedient servant.” His voice was low, like the purring of a giant cat, assured of its prey. “You are mortal and the beasts always hunger for rich blood. Is that not so, my followers?”

From the nightmares that had drifted along behind him as he had approached the hillock came grunts, slavering sounds, growls, and a full-throated howl from the wolf-man.

Gwennan tried to shape words of protest—even to scream—but she might have been struck dumb. It was that woman who was, and yet was not, Lady Lyle who spoke:

“It is true you have a choice. This is a very old struggle. Yet it is always new born within each of us—and each of you who are of the other blood also. Though you do not understand, feeling perhaps only the lightest touch of it in some dream. You—”

Tor’s laughter cut through her speech, drowned it out. One of the beasts (that which was a vile caricature of a man, haired and utterly terrifying to Gwennan) now strode past its master, clawed paws outstretched as if it sought to reach up and pull the girl down.

“You have no choice!” The man denied what the woman had said, crying that out to the girl with arrogant assurance. “You shall join this struggle—whether it is your will or not. There must be some measure of the old blood in you, outworld woman, or you would not have found

your way this far. Now that strength one of us can claim to our own purposes!”

The rock held her steady, as if it walled her about. In a way that rough textured stone remained for Gwennan a touch of reality. But it was the pendant which she really clung to, cupped in one hand, the other folded fast over it. The metal pulsed with growing heat. Still she set her teeth and held on as she would cling to a weapon. She did not know how she had come here, and she trusted nothing in this green-lit country. That mounted woman might wear Lady Lyle’s face (or rather a youthful semblance of that) but sight of those features carried no reassurance. There was an alien aura about all these lifeforms. Gwennan would willingly ally herself with neither. Now the ape-like monster was at the very foot of the hillock.

Gwennan pressed the watch more firmly. Within her she cried out for escape. Back! Just let her get back where she belonged—into her world where no nightmare would last, and no shaggy beast stump across the land!

And—

As if the very strength of her horror and terror had been enough to turn an unknown key, she once more plunged into that dark—into the place where she had no being, nor any right to travel. There was a whirling within her head, a thrust of pain, striking more at the essence of her identity than her body. Cold—and—pain—then once more light.

Here was not the half sight of a storm-ridden night. Nor did she front the green of that world in

which the hunters rode. Instead rich radiance shone about her. She blinked, half-blinded—still so shaken from her journey through the other-where that it was difficult to understand, to feel even truly alive.

Herself—who? This present uncertainty of identity fostered a continuation of the pain which had struck in the dark. Her thoughts could not be wholly formed, they were shattered— Who—and where? Color—masses of color against high walls. Sound rose and fell—the intoning of a solemn chant. She knew ail this aided one part of her, drawing together shattered shards of identity—but into a new pattern. Gwennan, that other Gwennan, was lost. Realization came as a forlorn cry from deep within her—a fading cry for help she could not answer.

She was—Ortha—Seer of the Great Temple. Did she not sit now on her accustomed place on the tripod seat of the Seer, before her the murky surface of the Future Mirror? The waves of color the Ortha part of her identified easily—Those were the robes of the Noble Blood permitted to gather here during a time of Farseeing. She need only turn her head and before her there would be the High Thrones, on them the Voice of the Past and the Future, and the Arm of Purpose, the Chosen in this generation.

Yes! Her back straightened proudly as the familiar cadences of the Calling Hymn sent energy flowing into her, preparing her for what she must do. Though, she was remembering far more clearly now, this was not one of the appointed seeing times—rather an emergency

meeting to which she had been summoned out of Pattern. There was danger and upon her would fall the full responsibility for any warning.

The Mirror—concentrate wholly on the Mirror—push back into the furthest corner of her mind that uneasiness, that feeling that she was another housed in this body—someone very different from Ortha, channel through which the Farseeing might rise and flow.

Under her steady gaze the dusky surface of the mirror changed. First came a clouding, as mist might gather, in its center, spreading outward in rolling waves towards the frame which held the full plate firm. Thicker grew the mist, stronger. Here and there one portion of it began to darken more than the rest.

Those shadow spots deepened, drew into them substance so they were no longer drifting, but stood sharp apart from the veiling which had given them being. She saw people now—small, distinct, if lacking in color—for all the Mirror revealed was not the outward seeming of any person, rather the life force which was the innermost spark.

Behind those sparks of life arose towers and walls—a city. Therein those building cores of spirit went about their affairs, even as did the men and women they represented in life. Swiftly the scene changed, one bit melting into the next. It was as if she were suspended above the rise of walls—those avenues filled with crowds—gazing down upon the far spread of the community from a bird’s winging height.

Yet that from which she so arose was a mighty

city—fast shrinking as she watched. From this place all the world was ruled. Its buildings in their splendor spread across leagues to form the mightiest monument the human kind knew. Now all dwindled away swiftly permitting her to see more and more of the land lying beyond its walls.

From where she flew—or floated—Ortha could no longer detect those life sparks. Such were too small, too lost in the wide land. Yet even higher her vision carried her. There was a bright thread of river—flowing to empty into the sea. Tiny splinters coasted on the surface of the waters—ships, the work of men in their pride—tying thus one portion of the world’s land to another. Higher still—she could no longer sight the splinters lost in the immensity of the sea.

Then—

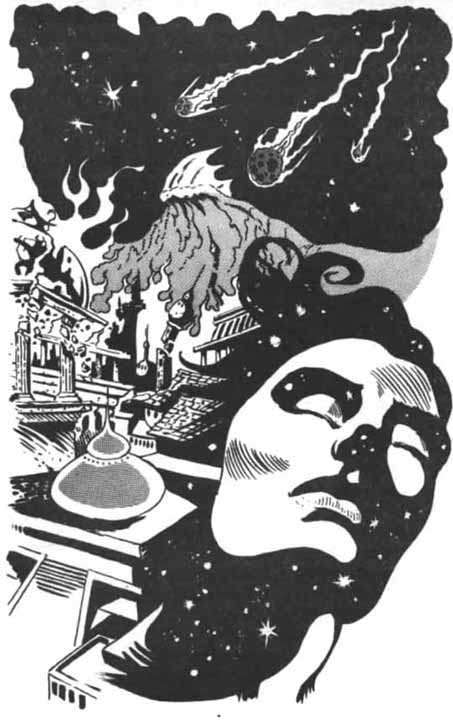

Out of the heaven, through which she spun, burst light—a ball so brilliant that it banished the somberness of the mirrored world. The blaze was blinding—yet the eyes by which she viewed it were not so bedazzled that she could not see clearly the horror which it brought.

It fell—that orb of fire, now it was accompanied by an army of lesser flares. Down these plunged, into the sea. As they struck, so the world she looked upon went mad.

Out of the water arose steam, and, following that, the very stuff of the earth itself appeared in ragged, uplifted ridges, spewing forth more fire. While the rest of the water (such as was not boiled away by the fires) rose, to roll towards the shores—mountain-high grew those masses of raging water. She saw the first frantic wave strike at the land furiously, spitting into tongues of moving destruction which swept all away—angry and tormented water against which no man nor anything of his handiwork might stand.

Inward raged the first of those great waves. Now Ortha was closer so she could clearly watch the sea take over and doom a world to destruction. A port city vanished as if it had never been. Yet the fury of the wave was in no way diminished. Rather it seemed somehow to be fed, energized by the very destruction it so wrought. On it went, covering leagues faster than any air-boat could flee, even with a storm wind behind it.

Now rings of fires showed to the north, bursting forth from the ground even as they had first arisen from the sea. Raw upthrusts of land belched forth molten rock and clouds of ash, tossing that in great masses towards the sky.

The waves washed on. Now she saw the tips of them loom up and up—and below lay the city which was like a hill of ants when an unheeding bootsole came crushing down. The water seemed to pause for a long instant of agony before it fell, to leave nothing but the swirling force of it.

She saw towers she had known all her life topple—among them that tallest one from which the star readers searched the heavens. There came a rocking of the land—water—fire—The wrath of powers which had slept since the forming of the world was being shaken into wakefulness. Man—man could not exist amid such fury. It was the end of the world which the Mirror was showing her. She wailed, a thin keening cry.

“Death,” she cried with stiff lips. “Death—

that which rides the heavens brings with it death—by water—by fire, by the torture of the earth itself. So does death come now upon us!”

She swayed from side to side on her Seer’s seat. Her voice raised into a higher wail:

“There shall be a new moon in our heavens to move above, hiding that one which is known now to us. With it comes that which shall fall and kill—showers of death. Out of the earth shall there be an answer, raised from grievous wounds, both fire and poison winds. Against that which comes even the Power which flows cannot save lives. There shall be nothing left but the water, fire and the raw wounds of the earth—”

“You lie!”

The words came cold and clear, cutting through her terror as a keen-edged knife might sever a cord. She was so jerked from her Seer’s trance, shaking, sick with what she had seen, also by the too quick severance of her vision.

Ortha’s arms were rigid on either side of her body, her fingers achingly curled about the edges of the tripod stool. Only that grip kept her in place. Now she turned her head to look toward the High Throne, feeling spittle seep from between her lips and trickle down her chin.

She who was the Voice of the Power leaned forward, her eyes like spear points seeking to impale Ortha with their hard, gemlike glitter. The blue of them was ice as they accused.

Now the Voice arose, her perfect body only lightly veiled by the gold gauze of her robe-of-presence, the gems of her girdle as hard and cold as her eyes. Over her shoulders flowed the long

waves of her sun-fair hair, so like unto the gold of her robe that it was hard to tell which was wispy fabric, and which was her natural veil.

“You lie—or else you have been touched by the Dark—” She gave judgment slowly and distinctly.

A murmur rippled among those gathered along the walls.

“It would seem,” the Voice continued, “that you do not see the truth, Seer. Thus it is time you be judged and the Power finds elsewhere a new servant.”

Ortha shook her head from side to side. That which she had seen still enwrapped her. She could not believe that the truth of her seeing was being questioned. Surely it was known that no Seer could falsify what the Mirror showed. Why should the Voice deny it—and her?

She looked now to the other, who shared the High Throne as the Arm of Purpose. He glanced first at Ortha and then to the Voice, but he made no move, spoke no word. It was the Voice who raised her hand in a small, commanding gesture.

Two came to stand on either side of Ortha. Hands clamped down with cruel strength upon her shoulders, exerting pressure to draw her up. The sacrilege of that profane touch broke through the spell the horror of Full Seeing had laid upon her. No man, be he priest, or guard, had the right to handle a Seer. She felt now the flame of anger rising in her. It was underpriests who were forcing her up and away from her seat—servants of the Arm—still

he

had given no order by word or gesture.

They swung her around now, away from the

Mirror, to fully face her accuser. The Voice continued to stare at her coldly, as if silently daring the girl to raise some protest, to call upon the Power in this, its own place of manifestation.

“You—” Ortha began, but it would seem that the Voice was not going to allow any Further word from a Seer she had declared discredited. One of the priests clapped his hand over the girl’s lips with force enough to bruise her skin against her teeth.

The Voice turned a little away, looked to those who had Power right, standing uneasy in their ranks, murmuring among themselves.

“This one is clearly forsworn. The heavens have been read for twenty months—there hangs nothing there to trouble us. It may be that the Dark One has found a weakness in our guardianship and so seeks to cause trouble. Or it may be that this one has looked too long. She shall spread no further lies.”

The Voice flung wide her arms and now came the manifestation of the Power which was housed in her and used her for its speaking tongue. From the tips of her outstretched fingers arose ribbons of light, weaving out and out. In all colors played that radiance, the green-blue of the sea, the rose-gold of the dawn, the pure white which was always the full Presence. Those rays pulsed into the air, streaming out, to hang above the heads of those present, bringing to them the peace and joy which was the gift of the Power.

In Ortha there was no peace nor joy—only anger and the beginning of a new fear, for she knew that the Power had used her truly, and that

what the Mirror had shown would come to pass—though the hour of that coming she did not know. How then could the Voice use the Power to deny its own truth? This kept Ortha in a state of bewilderment as the two who were now her captors marched her forth from the hall—those gathered there falling back as if they feared any close contact with one the Voice had declared to be of the Dark.