When Computers Were Human (12 page)

Read When Computers Were Human Online

Authors: David Alan Grier

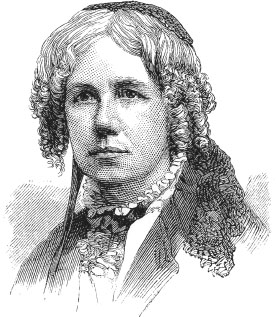

10. Maria Mitchell

For about half of the computers, including Maria Mitchell and Sears Cook Walker, Charles Henry Davis distributed detailed computing plans through the mail. Unlike Maskelyne, Davis did not prepare hand-drawn computing forms. Though he gave the computers a rough idea of how the sheet should look, he let them organize the computations as they desired. “You may fill up the sheets as much as possible, consistently with the clearness,” he told Maria Mitchell, and in so doing “can thus economize on paper.”

39

He provided paper and reference books to all of the computers, sending the supplies with a private forwarding company called Adams Express. Mitchell, who had a relatively meager library, often requested books for her work. In December 1849, she asked for a copy of

Theoria Motus Corporum Coelestium in Sectionibus Conicis Solem Ambientium

(

The Theory of the Motion of the Heavenly Bodies Moving about the Sun in Conic Sections

) by the German astronomer Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777â1855). This book, one of the last major astronomical texts written in Latin, had a fairly complete discussion of the techniques of astronomical calculations. “I have directed my bookseller to endeavor to get two copies [for the almanac office],” Davis responded, “and will add a third to the list for yourself if you wish it.” He concluded the letter by commenting, “I am glad you read Latin.”

40

The remaining computers, those who lived near Cambridge, worked at the almanac office. As far as we can determine, this office resembled the rooms of the British

Nautical Almanac

in London. There were worktables for the computers and a private area for the superintendent. One young computer recalled coming into the Cambridge office on a frosty January morning, taking a “seat between two well-known mathematicians, before a blazing fire.” It was an informal place, where new ideas of mathematics were freely discussed between calculations, as the “discipline of the public service was less rigid in the office at that time than at any government institution I ever heard of.” Each computer was expected to spend five hours a day in the office. “The hours might be selected by himself, and they generally extended from nine until two, the latter being at that time the college and family dinner hour.” All that Davis required was that the work was done on time.

41

The disjointed operation of the almanac, with some computers in Cambridge and some working from home, fit easily into the organizational structure of the navy. Davis kept track of each computer and the progress of his or her work. Four times a year, he would send pay vouchers to the computers that could be redeemed at any naval facility. The letters that accompanied these payments contain gossip, discussions of mathematics, news about astronomy, and even a few quotes from Shakespeare, who was clearly his favorite author. “Enclosed are your vouchers signed by myself,” he wrote to a new computer; “you had better negotiate them with a friendly broker, rather than with one where you hold a relation of Antonio to Shylock.”

42

Almanac computers earned between five hundred and eight hundred dollars per year for their work. Two of them doubled their income by checking and correcting the work of others in addition to doing their own computations.

43

After a year of calculations, Davis could report that work for the first issue, which would cover the year 1855, was progressing nicely. He told the secretary of the navy that his “small corps of computers” was employing the theories of the “illustrious Leverrier,” using the corrections of Airy, and reducing data from Maskelyne. He reminded the secretary that he had already made a special report of “a variation in the proper motion of one of the fundamental stars,” which he claimed “has led to a discovery of particular interest in stellar astronomy.” He summarized his progress by stating, “I have frequently expressed my wish that the

Nautical Almanac

should in every respect conform to the most advanced state of modern science and be honorable to the country and it is my determination to spare no effort by which this high object can be attained.”

44

Though Davis was confident that his computing staff would produce an American almanac that rivaled the publications of Europe, others were

not so certain. The potential users of the almanac, notably the merchant navigators and the surveyors, were willing to withhold their judgment until they saw the final product. These two groups were concerned about a basic element of the almanac, the location of the prime meridian. All almanacs had to establish a meridian, a line running through the north and south poles that would serve as a reference for the positions of stars. The

Connaissance des Temps

used the Paris meridian, which passed through the Cathedral of Notre Dame. The British

Nautical Almanac

was prepared for the Greenwich meridian. Originally, this line had been drawn through the Octagon Room of the Royal Observatory, but it had since moved to the site of a new telescope mount a few yards to the west. The original proposal for the American

Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac

instructed the navy to publish an “American

Nautical Almanac

, to be calculated for the meridian of Washington city.”

45

Davis did not like the idea of a Washington meridian. He preferred to use the Greenwich line, for he felt that it would produce the most accurate longitude calculations. “Our own vessels are constantly meeting those of Great Britain on the great highway of nations,” he noted, “and are in the habit of comparing with them their longitudes.”

46

By adopting the Greenwich meridian, the computers of the American almanac could use without additional calculations the vast catalogs of star data that George Airy was compiling at the Royal Observatory. However, the Greenwich meridian did not satisfy the computers of the Coast Survey or the surveys of the various American states. They wanted a meridian safely on the North American continent. Their calculations would be most accurate if they could physically measure parts of the meridian and if they could work without an ocean intervening between themselves and their baseline.

From one point of view, the argument between those favoring the Greenwich meridian and those who wanted a Washington meridian was an honest scientific disagreement. Each of the two groups advocated a procedure that was best for its own needs. Each of the procedures would provide an acceptable, though not perfect, solution for the other group. Yet the argument had symbolic and economic aspects beyond the scientific construction of astronomical tables. The symbolic problem was an offshoot of Manifest Destiny and the Monroe Doctrine. The American citizenry saw themselves settling the breadth of the North American continent, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. As settlers moved west, they would use the American

Nautical Almanac

to survey the territories and set the borders of new states. Congress would insist that those borders be specified from Washington, rather than from a meridian that passed through the suburbs of a foreign capital.

Davis believed that he had a clever compromise to the meridian problem,

one that would satisfy both navigators and surveyors. He proposed “to establish an arbitrary meridian at the city of New Orleans, which will be exactly six hours in time, or ninety degrees in space, from the meridian of Greenwich.”

47

The idea was an elegant technical solution, as it gave the United States its own meridian and allowed navigators to compute their position relative to Greenwich with little extra effort. Davis must have believed that his idea would be accepted without complaint, but just as he was starting the computations, he reported to the navy “that a âremonstrance' against my paper on the American Prime Meridian and against any change from the Meridian of Greenwich is circulated among the merchants and insurers of the cities of Boston and New York for signatures.”

48

The supporters of the “remonstrance” were uncomfortably close to Davis and his friends. Their leader, Ingersoll Bowditch (1806â1889), was the director of a Boston insurance firm, a friend of Benjamin Peirce, and a financial supporter of the Harvard Observatory. Their objections to a meridian at New Orleans were entirely economic. Bowditch believed that his business would be damaged by the change in meridians. He was a partner in a firm that republished the British

Nautical Almanac

in the United States. The objections of the other merchants and insurers were more speculative. They were concerned that the ports of Boston and New York would decline if New Orleans had a meridian passing through it. New Orleans already possessed a substantial advantage over the Atlantic ports, as it had a navigable waterway, the Mississippi River, with access to the vast center of the continent. With the meridian, reasoned Bowditch and his supporters, New Orleans would become a destination for ships needing to adjust their chronometers. These ships would divert trade to the south, as none of the captains would want to travel empty.

Davis attempted to counter the claims of Bowditch, but he had lost the battle almost from the beginning. He argued that his proposal was “founded on principles of science” and would contribute “towards improving the safety of navigation, and completing the geography of the seas,” but neither idea swayed his opponents.

49

The debate had turned toward economic issues and way from scientific merit. In this field, Bowditch held the greater power. By the spring of 1850, Davis had abandoned his idea for the meridian and accepted a solution that divided the American almanac into two parts. The first part, the

American Ephemeris

, would be computed relative to a meridian that passed through the Naval Observatory in Washington. This meridian would be used by surveyors as they set the borders of Wyoming, Colorado, Oregon, and the other western states. These lines would fall at integral number of degrees west from the Naval Observatory in Washington, rather than from the Royal Observatory in England. The second part of the almanac, the

Nautical

Almanac

, would be prepared using the Greenwich meridian and be used by the nation's sailors.

The double meridian scheme put extra demands upon the almanac computers, as it required them to prepare more tables, but it had little impact upon the structure of the computing staff. Davis did not have to restructure his computers in order to make them more efficient because he had substantial support from both the navy and Congress. The navy had initially allocated $6,000 a year for the almanac, most of which was spent on the salaries of computers. By the spring of 1850, Davis had concluded that this figure was insufficient, especially with the requirement to prepare two sets of tables. He requested and received $12,000 for the second year of operations. This figure also proved to be too little. For his third year of operations, Davis asked for $18,000.

50

The navy granted this request, but the increase drew the attention of the U.S. Senate. In May of 1852, Senator John P. Hale (1806â1873) of New Hampshire rose from his desk on the Senate floor and asked the navy to justify its expenditures on the almanac. Though he expressed his concern over the size of the almanac budget, Hale was more interested in a key element of Davis's plan, the cooperation of naval officers and a civilian computing staff. He might have been less concerned if the computers had been “mere drudges” and could have been drawn from any state of the union. However, he knew that all of Davis's computers were somehow connected to Benjamin Peirce or Harvard College.

51

Hale demanded that the secretary of the navy “inform the Senate, where, and at what Observatory, the observations and calculations for the â

Nautical Almanac

' are made.” Like any skilled politician, Hale knew the answer to his question before he strode onto the Senate floor and asked to be recognized. “I think that I am not incorrect,” he informed his colleagues, “when I say that all this expense has been incurred, not at the National Observatory but at the observatory of Cambridge College in Massachusetts.”

52

“Cambridge College” was, of course, Harvard. He probably misidentified the school as a way of emphasizing its location. If he expected this charge to stir the Senate to action, he was disappointed. Even those who objected to government support for private institutions sat in their seats. Any discussion of the almanac was ended quickly and decisively by a senator who derided Hale as possessing “an absolute and unappeasable hostility to any connections of science with the Naval Department in any form.”

53

Though Hale's comments lasted but a few moments, they pushed Charles Henry Davis to respond. His plans would quickly fail if Congress reduced his budget or dictated the kinds of computers that he might hire. He wrote a detailed defense of his organization, addressed to the secretary of the navy but published in the

American Journal of Science and Arts

and

circulated as a pamphlet. He confronted Hale on the narrow point of the attack, explaining that “no Observatory, neither that at Washington nor that at Cambridge, as has been suggested, received any portion whatever of the sum appropriated for the â

Nautical Almanac

.'” This statement was entirely true, but it did not address the point that many of the computers had a connection to Harvard. Davis tried to deflect this issue by stating that the almanac required the “most illustrious genius and the most exalted talents” and that it was not “a work of insignificant value or trifling labor.” He claimed that the new almanac “is considered by American astronomers and mathematicians as a work of consummate utility and of real national importance, resembling in this respect the

Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris

of Great Britain, the

Connaissance des Temps

of France and the

Astronomical Almanac

of Prussia.”

54