When the King Took Flight (11 page)

Read When the King Took Flight Online

Authors: Timothy Tackett

Soon after Fersen had returned, the king's sister, Elizabeth, who

had donned her own disguise and slipped out of her room through

a secret door built into the apartment's woodwork, made her way

out of the palace to the waiting hackney cab, where Fersen directed

her to the correct door. The king was supposed to leave next, but at

the last minute General Lafayette and Bailly, the mayor of Paris, arrived unannounced at the palace, and Louis was obliged to speak

with them. Only at about half past eleven, when the two Parisian

leaders had left, could he pretend to go to bed, dismiss his servants,

and then get up, put on his own disguise, and walk cane in hand

with Malden to the waiting carriage. With his usual phlegm, he even

stopped to buckle his shoe as he crossed the courtyard. Last to depart was the queen herself. By some accounts she nearly collided

with Lafayette who was also just leaving the palace. But dazzled by

the torches held around him and preoccupied with other matters,

the general took no notice of the lone woman walking in the shadows, and after an anxious moment she, too, climbed into the cab.'

It was now about half past twelve, an hour later than planned. As

the family embraced one another and settled into the small carriage,

Fersen drove across Paris, with Malden at the back as footman, advancing slowly for fear of attracting attention. Rather than taking

the most direct route to the Saint-Martin's tollgate, he drove first to

the northwest along Rue de Clichy, where he verified that the berline had been removed. He was also anxious to avoid the popular

northeastern neighborhoods of Paris, where suspicions were always high and where activity in the streets continued well into the night.

When he finally arrived at the gate, he spent several anxious minutes looking for Moustier, Sapel, and the berline, which had been

parked in the dark much farther away than he had expected. Once

he had located it, Fersen and the two bodyguards quickly transferred the travelers into the larger coach, pushed the smaller cab

into a ditch, and set off along the main eastbound road out of Paris.

The various delays had put them two hours behind schedule. It was

the shortest night of the year, and the first signs of dawn were al ready appearing. Fersen shouted to his coachman to drive at full

speed: "Come now, Balthasar," he said, as Sapel himself remembered it; "be bold, be quick! Your horses can't be tired, push them

faster!" Half an hour later the berline arrived at the first relay post

of Bondy, where Valory was waiting with a change of horses.'

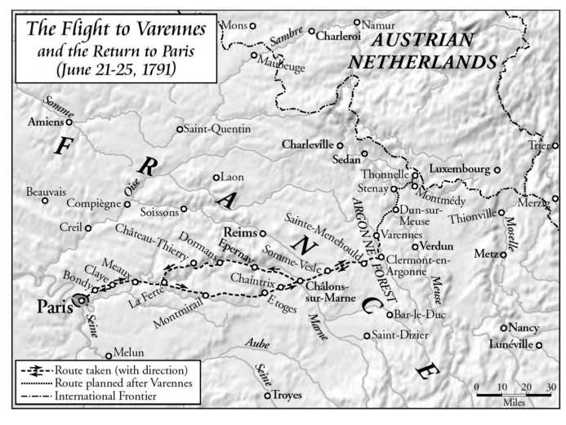

[To view this image, refer to

the print version of this title.]

Departure of Louis XVI from the Tuileries palace at /2.30 A.M. on June 21, 1_79/.

The king, holding a lantern, leads the escape party across the Tuileries courtyard to meet Fersen and the waiting hackney cab. In reality, most of the party

left one at a time.

Here Fersen left the party. He had brought off his part of the

conspiracy with aplomb and audacity, engineering an almost miraculous escape from the Tuileries and from Paris. He planned now to

travel separately on horseback, northward into the Austrian Netherlands and then along the border just outside the kingdom, meeting the family again in Montmedy. "Goodbye, Madame Korff," he

said simply, addressing the disguised queen. And he rode off toward Le Bourget as the family headed east.10

At their next relay stop, in Claye, the travelers completed their

party, picking up the cabriolet containing the two nurses. As the sun

rose-somewhat after four-the caravan headed across the rolling

plains of Ile-de-France and Champagne. They were hardly an inconspicuous ensemble. The yellow cabriolet, the large black berline

with its yellow frame, and the three bodyguards in bright yellow

coats-Valory leading on horseback, Malden atop the larger coach,

and Moustier on horseback bringing up the rear-attracted the attention of countrypeople and townsmen wherever they passed." To

be sure, this was the main road from Paris to Germany, and the passage of wealthy travelers in luxurious vehicles was by no means unprecedented. But as they advanced farther toward Lorraine, observers focused in particular on the three guards. Apparently Moustier

had chosen yellow uniforms quite by accident. For the local people,

however, they seemed remarkably similar to the livery of the prince

de Conde, the detested emigrant leader of a counterrevolutionary

army and seigneurial lord of numerous territories in this region of

France.'Z

The route followed was one of the major highways of the kingdom, broad, straight and well maintained, lined with trees for the

most part and with a roadbed-paved with stones for about half

the journey and thereafter covered in gravel-raised well above the fields. Portions of the road had been completed only in 1785.

Like many other wealthy long-distance travelers, the king's party

changed both horses and drivers at each of the royal relay posts

along the way. Valory generally rode well ahead of the others to

rouse the "post-master" at the next stop and have the horses prepared, ready to be hitched to the arriving carriages. At each post

they requested ten or eleven fresh horses-six for the berline, two

or three for the cabriolet, and two mounts for Valory and Moustier.

Each team was accompanied by one or two "drivers" or "guides,"

who usually rode astride one of the carriage horses, directing the

party to the next relay station and then returning the teams to their

home post. Louis carried a sack of gold coins that he periodically

distributed to Valory to pay and tip the drivers." They normally

made about nine or ten miles per hour on the road, although if one

also takes into account the fifteen to twenty minutes spent at each of the nineteen relay stops, the average for the trip was closer to seven

miles per hour.'

As the day warmed and the carriages moved steadily across the

countryside, the horses changed regularly and without difficulties,

the travelers felt a sense of liberation and euphoria. The weather

was hot and humid, but they encountered no rain. At one point,

probably near Etoges, one of the berline's wheels hit a stone road

marker, and four of the horses stumbled, breaking their traces. The

thirty- or forty-five-minute repair job put the party even further behind schedule." But otherwise the drive itself went without a hitch.

The most dangerous part of the trip seemed to lie behind them, and

now it was simply a question of arriving at Somme-Vesle, where

they would be watched over and taken in care, if necessary, by

Choiseul's cavalry.

Inside the coach, the family ate a pleasant picnic breakfast with

their fingers, "like hunters or third-class travelers," as Moustier described it. They shared accounts of their experiences in leaving the

Tuileries. The queen commented on how Lafayette must be embarrassed and squirming now that the royal departure had been discovered. The king took out his maps and the itinerary he had carefully

prepared in advance, announcing each village or relay post as they

passed by. It was only his third trip outside the region of Paris, the

first since his glorious journey to Cherbourg in 1786, and he indulged his passion for geography and detailed lists. The queen took

charge of assigning the roles they would all assume-as she had

once delighted in doing with her courtiers in the Petit Trianon palace near Versailles. Madame de Tourzel would be the baroness de

Korff, the dauphin and the princess would be the baroness' two children, and Madame Elizabeth and Marie-Antoinette would be her

servingwomen. The queen and the king's sister were appropriately

attired for such roles in simple "morning gowns," short capes, and

matching hats. As for the king, dressed in his commoner's frock

coat with a brown vest and a small round hat, he would be Monsieur Durand, the baroness' business agent.'

But the travelers soon tired of their role-playing and the rigors of guarding a strict incognito. Louis in particular had never been

adept at pretending to be someone he was not. In any case, he was

convinced that with Paris behind them, with its Jacobin club and fanatical newspapers and wild-eyed mobs, everything would be different; the king and queen would now be properly respected. As the

heat increased, they lowered the blinds, took off their hats and veils,

and watched the peasants laboring in the fields. And the peasants

watched back, wondering at the identity of these wealthy aristocrats in their curious yellow and black caravan. At the long uphill

grades, like the one ascending from the Marne Valley after La Ferte-

sous-Jouarre, most of the party got out and walked along behind

while the horses labored up the hill. Later in the day the king began

stepping out at the relay stops, relieving himself at the "necessary

shed," and even stopping to chat with the people gathered around,

asking about the weather and the crops, as he had talked in his

youth with the laborers outside Versailles. The bodyguards and

the two nurses worried at first about the king's insouciance, and

Moustier tried to shield him from a group of gaping countrypeople

at one of the rest stops. However, Louis told the guard "not to

worry; that he no longer felt that such precautions were necessary;

and that the trip now seemed to be free of all uncertainty." In the

end, the bodyguards concluded that the royal members knew what

they were doing and that they themselves need not be concerned."

And the king was in fact recognized. A wagon driver, Francois

Picard, was convinced he had seen the monarch when the horses

were changed outside the relay in Montmirail. Louis was recognized again three stops further, in Chaintrix, by the post-master,

Jean-Baptiste de Lagny, and his son-in-law Gabriel Vallet, both of

whom had attended the Festival of Federation in Paris in 1790.

Here, as local memory would have it, the whole royal family got

out and took refreshments at the inn attached to the relay, leaving

two small silver bowls stamped with the royal insignia in appreciation. In any case, Lagny assigned Vallet to drive the berline on to

Chalons-sur-Marne, and the son-in-law immediately whispered the

news to the post-master there, a close friend of the family."

As they drove into Chalons about four in the afternoon, the travelers might have had cause to be nervous. It was by far the largest

town between Paris and Montmedy, and there were undoubtedly

several local notables who had seen the royal couple in Versailles.

Yet Louis seems to have taken no more care here than in the small

rural posts he had just traversed. In addition to the post-master

Viet, several other persons seem to have recognized them. "We

were recognized by everybody," recalled Madame Royale. "Many

people praised God to see the king and wished him well in his

flight."" Whether people were really pleased to see the king leave

Paris, or were simply too shocked to know what to do, Viet and his

stable hands quietly changed the horses and watched the carriages

drive out of town. The mayor was informed almost immediately,

but he, too, was uncertain what to do. Only several hours later,

when messengers began arriving from Paris, confirming the news

of the king's escape and sending the Assembly's decree to stop him,

did the municipal government swing into action."

On leaving Chalons and heading east toward the border of

Lorraine, the travelers were extremely optimistic, feeling they had

crossed their last major obstacle and would soon be in the care of

the duke de Choiseul and his loyal cavalry. With his detailed itinerary at hand, the king was aware that they had fallen nearly three

hours behind, yet it probably never occurred to him that this could

pose a problem. The mood shifted abruptly, however, as they came

in sight of the small relay post at Somme-Vesle, isolated on the

main road at some distance from the village. In the great expanse of

openfield farmland surrounding them there were no troops in sight.

Valory cautiously inquired and discovered that the cavalry had indeed been there, waiting across a small pond beyond the relay, but

that the troops had been harassed by local peasants and had left an

hour earlier. At first the travelers thought that Choiseul might simply have pulled back to a quieter spot farther down the road. Yet

when they reached the next relay, he and his men were still nowhere

to be seen. As the family drove in the early evening toward the

town of Sainte-Menehould, framed against the dark band of the Argonne Forest, they were beset, in Tourzel's words, by "terrible

anxiety.""

Over the previous days, the organization of the king's escort had

initially gone quite smoothly, despite the modifications caused by

Louis' last-minute decision to delay his departure by one day.

As Fersen and the royal family completed their preparations and

launched the escape from Paris, General Bouille had been activating

a whole series of prearranged troop movements to prepare a reception for the king. The general himself had left his headquarters in

Metz on June i6, informing local officials that he was off to inspect

the frontiers for possible Austrian troop activities. Orders were

given to begin concentrating soldiers and large quantities of food

and supplies in Montmedy. On June zo he had arrived in Stenay, the

fortified town on the Meuse between Montmedy and Varennes. His

youngest son and another officer, the count de Raigecourt, had been

sent ahead to Varennes with a team of relay horses, joining some

forty German troops already stationed there. To avoid suspicion,

they were to keep the horses in the stables of an inn just east of the

river, leading them to the southern edge of Varennes only when

they were notified of the king's impending arrival. During the night

of June 20-21 the elder Bouille and a small group of officers had secretly ridden eight miles farther south to wait for the royal party in

a secluded position just north of the small town of Dun. Meanwhile, other contingents of German cavalry were led from the

south by commanders Damas and Andoins to take up positions in

Clermont and Sainte-Menehould respectively. On the morning of

June 21, Francois de Goguelat himself had led forty hussars from

Sainte-Menehould to Somme-Vesle, arriving about noon to meet

the duke de Choiseul-and the hairdresser Leonard-who were

waiting at the relay post.22