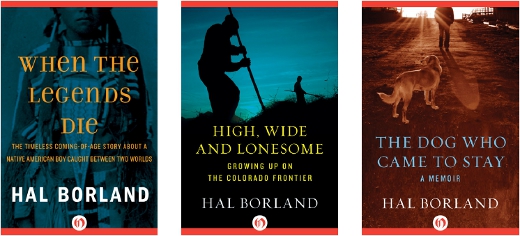

When the Legends Die (33 page)

Read When the Legends Die Online

Authors: Hal Borland

His rifle was resting on his knee, but his hands were quivering, his eyes bleared. He forced himself to steadiness, and the shot shook the earth. The rocks and the trees trembled. The does were gone in one quick rush, but the buck stood for a long moment as though unhurt. Then it took one step, faltered, went to its knees and fell with a long sigh of expended breath. Then there was silence.

He crossed the stream and his knife glinted in the thinning light. The buck’s blood spilled from the slit throat and he whispered, “Earth, drink this blood that now belongs to you.” He waited till the flow had stopped, then knelt and slit the skin down the buck’s breast and between its legs and began to lay it back from the warm red meat. He butchered it the old way and he carried every part back to his camp. Then he broke his fast. He cooked and ate, and he slept.

H

E BUILT THE LODGE

there on the first bench of Granite Peak. But before he cut one pole for the lodge he set up a drying rack, sliced the venison into thin strips and hung it to cure in the smoke and slow heat of a smudged fire. He fleshed the hide and started the tanning with a mixture of liver and brains. He put aside sinews for sewing, saved antlers and bones from which to make awls, scrapers and other tools, boiled out and saved marrow fat. He used every usable part of the buck, as he had promised.

Then he cut poles in the pine thicket, choosing them carefully to leave no obvious gaps, and he built the lodge and banked it with brush and earth and leaves to make it winter-warm and mask its newness, make it a part of the mountainside. When he had finished the lodge he took another deer, cured more meat for the winter; and he made rawhide from a part of that skin, for moccasin soles and snowshoe webbing, made leather from the rest of it for winter moccasins and leggings. He caught trout and smoked them. He gathered sweet acorns and pinon nuts. He found a patch of wild white peas and gathered their seeds, and he dug and dried the roots of elk thistle. He cut and trimmed ironwood and bent and shaped it to dry and season for snowshoe frames. He stowed firewood in the lodge.

Hard frost came and passed. Aspen leaves fell and lay crisp and briefly yellow in the valleys, and the dark flame of the scrub oaks faded to the brown of their bitter little acorns. The sky was clean and clear, the air was crisp. The season turned to that pause when the mountains rest between summer and winter and a man knows, if there is any understanding in him, the truth of his own being.

Now he had time for the lesser tasks. He cut the leather for winter moccasins and shaped their rawhide soles. He made bone awls and chose sinew for the sewing. And one afternoon, sitting in the sun, sewing the sole on a moccasin, he thought again of the bear. He had gone over the hunt a dozen times, remembering each detail, and he had wondered what would have happened if he had squeezed the trigger. He might have made the kill. But if his eye had blurred, if his hand had wavered the slightest trace, both he and the bear would now be dead. He had little doubt of that. If he had missed the heart with the first shot the bear, numbed to further pain, would have taken a whole magazine of bullets and kept coming, an infuriated devil. It would have caught him among the rocks and killed him even as it was dying.

He had gone over that a dozen times, what happened and what might have happened. Now, sitting in the sun with the peace of the world around him, he began examining why he was driven to the hunt in the first place and why he acted as he did. He sat back and shifted the coil of dry sinew in his mouth, softening it with his saliva for sewing. He felt it with his tongue, drew out an end and tested it with his fingers. It was still too stiff and wiry. He picked up the rawhide sole and went on making careful thread holes with the bone awl.

Searching for the whys, he reached back to beginnings. To the cub, to Blue Elk, to the school, to the quirting and the denial in the moonlight. That was where the hunt began, away back there. Not the actual bear hunt, but the hunt that led to the bear years later. That was when he began hunting down all the painful things of the past, to kill them. And one by one, over the years, he did kill them. All except the bear. All except his childhood, his own heritage. He could even list them now, Blue Elk, Benny Grayback, Neil Swanson, Rowena Ellis, Red Dillon, Meo—he paused, considering Meo, then nodded, knowing he killed Meo too, when he burned the cabin. He could see Meo’s garden patch, weedy but still with the mark of Meo’s hand upon it, withering in the searing heat. No, he didn’t shoot or knife or choke any of them to death. There are other ways to kill. He killed them, the memory of them, in the arena, when he became Killer Tom Black.

He killed them all, except the bear. And then he came back to the mountains, having looked death in the face himself. He came back to heal his body, to ride again, to go on trying to kill the one thing he hadn’t been able to kill—the bear, his own boyhood. And he met the bear, and tried to go away again, and had to come back and hunt it down.

He straightened up to ease his shoulders and looked across the valley toward Horse Mountain, fifteen miles away but looking less than half that in the clean, clear air. He thought of the day the bear came down and killed the lamb, the way he ran after it, unarmed, and told it to go away as he had so long ago. Then he tried the sinew again and found it pliable. He drew out an end and began to sew the rawhide sole to the soft leather of the upper.

He tried to go away, after that, thinking he could forget the bear. And had to come back, knowing he couldn’t forget. Thinking he could hunt it down, make an end to the matter with a bullet and leave the bear to rot and maggot away. Only to find, when the moment came, that he had done his killing, killed so many things, so many memories, that there was nothing left to kill except himself. Facing that and not knowing who he was, forgetting even his own identity, he didn’t kill the bear. He went in search of himself.

He sewed to the end of the sinew and drew another strand from his mouth, remembering the penance trip up the mountain. The memory of the trip itself was vague because he had been so weak from fasting that he had done what he had to do by instinct, by willpower, knowing he must go or die in the effort. Knowing this was the answer, the ultimate hunt. Not the bear hunt, but the penance journey up the mountain. The memory was vague, but the dreams, the visions, were still clear. He accomplished, on that trip up the mountain, what he set out to accomplish, unknowing, on the bear hunt. He killed himself, the self he had been for so long. He killed Tom Black, the vengeful demon who rode horses to death. He had set out to kill a boyhood, when he turned back at Piedra Town that morning, and he had succeeded, at last, in killing a man and in finding himself.

He sighed, knowing why he had come back. And he remembered a chipmunk he had as a small boy, a pet that came when he called and sat in his hand. He had asked his mother the meaning of the stripes on the chipmunk’s back. Those stripes, she said, were the paths from its eyes, with which it sees now and tomorrow, to its tail, which is always behind it and a part of yesterday. He had laughed at that and said he wished he, too, had a tail. His mother had said, “When you are a man you will have a tail, though you will never see it. You will have something always behind you.”

Now he understood. Now he knew that time lays scars on a man like the chipmunk’s stripes, paths that lead from where he is now back to where he came from, from the eyes of his knowing to the tail of his remembering. They are the ties that bind a man to his own being, his small part of the roundness.

He shifted the moccasin between his knees and awled more thread holes in the tough sole, then went on sewing.

It had been a long journey, he thought, the long and lonely journey a man must make when he is lost and searching for himself, particularly one who denies his own past, refuses to face his own identity. There was no question now of who he was. The All-Mother’s words, in the vision, stated it beyond denial: “He is my son.” He was a Ute, an Indian, a man of his own beginnings, and nothing would ever change that. He had tried to change it, following Blue Elk’s way; and he had tried, following Red Dillon’s way. He had tried, following the way of Tom Black. And still he had to find the way back to himself, to learn that none of their ways could erase the simple truth of the chipmunk’s stripes, the ties that bind a man to the truth of his own being, his small part of the enduring roundness.

He finished the moccasin and examined it, was satisfied with his workmanship. His hands remembered, and his mind had begun to remember and accept. The moccasin, like that lodge, was a part of the acceptance. He was not a clout Indian, never would be again. But for a time he had to go back to the old ways, make his peace with his world and with himself. He had begun to feel that peace, at last. In time, he would go down to Pagosa, talk with Jim Thatcher, if he was still alive. Learn what happened to Blue Elk, try to understand why he sold his own people as he did. He would go to the reservation, eventually, to the school, and see what was happening there now, try to understand that, too. But never again would he go back to the arena. He had ridden his broncs, fought and killed his hatreds and his hurts. He was no longer Tom Black. He was Tom Black Bull, a man who knew and was proud of his own inheritance, who had come to the end of his long hunt.

He went into the lodge, put the moccasin carefully away with its mate, put the awl in its case and laid away the coil of sinew. He stirred the pot of stew and thrust a fresh stick of wood into the coals. Then he went out into the evening and up the slope a little way to a big rock where he could see Horse Mountain and Bald Mountain and the whole tumbled range of mountains. He sat there and watched the shadows darken in the valleys, and when the sun had set he whispered the chant to the evening. It was an old chant, a very old one, and he sang it not to the evening but to himself, to be sure he had not forgotten the words, to be sure he would never again forget.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

copyright © 1963 by Hal Borland

cover design by Open Road Integrated Media

978-1-4532-3234-7

This edition published in 2011 by Open Road Integrated Media

180 Varick Street

New York, NY 10014

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA

Available wherever ebooks are sold