When the Moon Is Low

For Zoran, who made me the luckiest girl in the world when he promised to always be my best friend

The small man

Builds cages for everyone

He

Knows.

While the sage,

Who has to duck his head

When the moon is low,

Keeps dropping keys all night long

For the

Beautiful

Rowdy

Prisoners.

—“DROPPING KEYS” BY HAFIZ, A FOURTEENTH-CENTURY SUFI POET

CONTENTS

- Dedication

- Epigraph

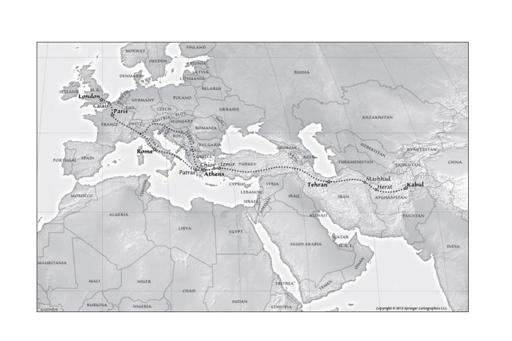

- Map

- Prologue: Fereiba

- Part One

- Chapter 1: Fereiba

- Chapter 2: Fereiba

- Chapter 3: Fereiba

- Chapter 4: Fereiba

- Chapter 5: Fereiba

- Chapter 6: Fereiba

- Chapter 7: Fereiba

- Chapter 8: Fereiba

- Chapter 9: Fereiba

- Chapter 10: Fereiba

- Chapter 11: Fereiba

- Chapter 12: Fereiba

- Chapter 13: Fereiba

- Chapter 14: Fereiba

- Chapter 15: Fereiba

- Chapter 16: Fereiba

- Chapter 17: Fereiba

- Chapter 18: Fereiba

- Chapter 19: Saleem

- Chapter 20: Saleem

- Chapter 21: Fereiba

- Chapter 22: Saleem

- Chapter 23: Saleem

- Chapter 24: Saleem

- Chapter 25: Saleem

- Chapter 26: Saleem

- Chapter 27: Saleem

- Chapter 28: Saleem

- Chapter 29: Saleem

- Chapter 1: Fereiba

- Part Two

- Chapter 30: Saleem

- Chapter 31: Fereiba

- Chapter 32: Saleem

- Chapter 33: Saleem

- Chapter 34: Saleem

- Chapter 35: Fereiba

- Chapter 36: Saleem

- Chapter 37: Saleem

- Chapter 38: Saleem

- Chapter 39: Fereiba

- Chapter 40: Saleem

- Chapter 41: Saleem

- Chapter 42: Saleem

- Chapter 43: Saleem

- Chapter 44: Saleem

- Chapter 45: Fereiba

- Chapter 46: Saleem

- Chapter 47: Saleem

- Chapter 48: Saleem

- Chapter 49: Saleem

- Chapter 50: Saleem

- Chapter 51: Saleem

- Chapter 52: Saleem

- Chapter 53: Saleem

- Chapter 54: Saleem

- Chapter 55: Fereiba

- Chapter 56: Saleem

- Chapter 30: Saleem

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary

- About the Author

- Also by Nadia Hashimi

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

THOUGH I LOVE TO SEE MY CHILDREN RESTING SOUNDLY, IN THE

quiet of their slumber my uneasy mind retraces our journey. How did I come to be here, with two of my three children curled on the bristly bedspread of a hotel room? So far from home, so far from voices I recognize.

In my youth, Europe was the land of fashion and sophistication. Fragrant body creams, fine tailored jackets, renowned universities. Kabul admired the fair-complexioned imperialists beyond the Ural Mountains. We batted our eyelashes at them and blended their refinement with our tribal exoticism.

When Kabul crumbled, so did the starry-eyed dreams of my generation. We no longer saw Europe’s frills. We could barely see beyond our own streets, so thick were the plumes of war. By the time my husband and I decided to flee our homeland, Europe’s allure had been reduced to its singular, sexiest quality—peace.

I AM NO LONGER A NEW BRIDE OR A YOUNG WOMAN. I AM A

mother, farther from Kabul than I have ever been. My children and I have crossed mountains, deserts, and oceans to reach this dank hotel room, utterly unsophisticated and unfragrant. This land is not what I expected. Good thing all that I coveted from a youthful distance is no longer important to me.

Everything I see, hear, and touch is not my own. My senses burn with the foreignness of my days.

I dare not disturb the children, as much as my heart wishes they would wake and interrupt my thoughts. I let them sleep because I know how exhausted they feel. We are a tired bunch, sometimes too tired to smile at one another. As much as I’d like to sleep, I feel obligated to stay awake and listen to the nervous banging in my head.

I long to hear Saleem’s determined footsteps in the hallway.

My wrist is bare. My gold bangles and their melancholy clink are gone. It was my plan to sell them. Our pockets are too empty for us to brave the rest of our journey. There is still a long road ahead before we reach our destination.

Saleem is so eager to prove himself. He’s more like his father than his adolescent heart could realize. He thinks of himself as a man, and much of that may be my doing. Too many times I’ve given him reason to believe he is one. But he is not much more than a boy, and the unforgiving world is eager to remind him of it.

I’m going, Madar-

jan.

If we hide in a room every time we are nervous, we will never make it to England.

There was truth to what he said. I bit my tongue, but the gnawing feeling in my stomach condemns me for it. Until my son returns, I will stare at the sickly white walls, paintings of anchors, faded artificial flowers. I will wait for the walls to collapse, for the anchors to crash to the floor and the flowers to turn into dust. I need Saleem to come back.

I think of my husband more now than I did in those days he stood by my side. What foolish and ungrateful hearts we have when we are young.

I wait for the doorknob to turn, for my son to enter, boasting that he’s done for our family what I could not. I would give anything for him not to risk as much as he does. But I have nothing to barter for such a naïve wish. All I have is spread before me, two innocent souls lightly stirring in their own troubled dreams.

I can touch them still, I remind myself. Saleem will return, God willing, and we will be as close to complete as we can hope to be. One day, we will not look over our shoulders in fear or sleep on borrowed land with one eye open or shudder at the sight of a uniform. One day we will have a place to call home. I will carry these children—my husband’s children—as far as I can and pray that we will reach that place where, in the quiet of their slumber, I, too, will rest.

MY FATE WAS SEALED IN BLOOD ON THE DAY OF MY BIRTH. AS I

struggled to enter this twisted world, my mother resigned it, taking with her my chances of being a true daughter. The midwife sliced through the cord and released my mother from any further obligation to me. Her body paled while mine pinked; her breaths ceased as I learned to cry. I was cleaned off, wrapped in a blanket, and brought out to meet my father, now a widower thanks to me. He fell to his knees, the color leached from his face. Padar-

jan

told me himself that it was three days before he could bring himself to hold the daughter who had taken his wife. I wish I couldn’t imagine what thoughts had crossed his mind, but I can. I’m fairly certain that had he been given the choice, he would have chosen my mother over me.

My father did his best but he wasn’t built for the task. In his defense, it wasn’t easy in those days. Or in any days, for that matter. Padar-

jan

was the son of a vizier with local clout. People in town turned to my grandfather for counsel, mediation, and loans. My grandfather, Boba-

jan,

was even tempered, resolute, and sagacious. He

made decisions easily and didn’t waver in the face of dissent. I don’t know if he was always right, but he spoke with such conviction that people believed he was.

Soon after he was married, Boba-

jan

had come upon a substantial amount of land through a clever trade. The fruits of this land fed and housed generations of our family. My grandmother, Bibi-

jan,

who died two years before my tragic birth, had given him four sons, my father being the youngest. Her four sons had all grown up enjoying the privilege their father had secured for them. The family was respected in town, and each of my uncles had married well, inheriting a portion of the land on which they each started their own families.

My father, too, owned land—an orchard, to be exact—and worked as a local official in our town, Kabul, the bustling capital of Afghanistan tucked away in the bosom of central Asia. The geography would become important to me only later in my life. Padar-

jan

was merely a faded carbon copy of my grandfather, not penned with enough pressure to imprint strong characters. He had Boba-

jan

’s good intentions but lacked his resolve.

Padar-

jan

had inherited his piece of the family estate, the orchard, when he married my mother. He devoted himself to that orchard, tending to it morning and night, climbing its trees to pluck the choicest fruits and berries for my mother. On hot summer nights, he would sleep among the trees, intoxicated by the plush branches and the sweet scent of ripe peaches. He would barter part of the orchard’s yield for household staples and services and seemed satisfied with what he was able to garner in this way. He was content and didn’t seek much beyond his lot.

My mother, from the bits and pieces I heard growing up, was a beautiful woman. Thick locks of ebony fell below her shoulders. She had warm eyes and regal cheekbones. She hummed while she worked, always wore a green pendant, and was well known for her mouthwatering

aush,

delicate noodles and spiced ground beef in a yogurt broth that warmed bellies in the harsh winter. My parents’ short-lived marriage

had been a happy arrangement, judging by the way my father’s eyes would well up on the rare occasion he spoke of her. Though it took me almost a lifetime to do it, I put together what I knew of my mother and convinced myself that she had most likely forgiven my trespass against her. I would never see her, but I still needed to feel her love.

About a year after their marriage, my mother gave birth to a healthy baby boy. My father took a first look at his son’s robust form and named him Asad, the lion. My grandfather whispered the

azaan,

or call to prayer, in Asad’s newborn ear, baptizing him as a Muslim. I doubt Asad was any different then. Most likely, he didn’t hear Boba-

jan

’s

azaan,

already distracted by mischief and ignoring the call to be righteous.