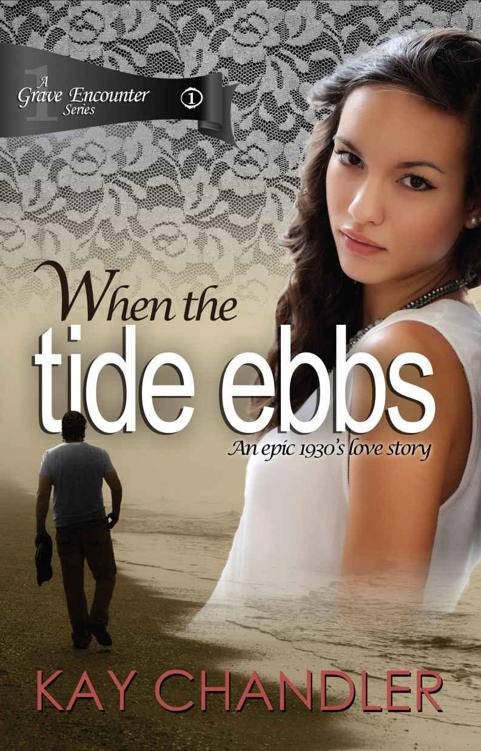

When the Tide Ebbs: An epic 1930's love story (A Grave Encounter)

Read When the Tide Ebbs: An epic 1930's love story (A Grave Encounter) Online

Authors: Kay Chandler

When the Tide Ebbs

GRAVE ENCOUNTERS

Book I

A 1930s Epic Love Story

KAY CHANDLER

A multi-award winning author

This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or used factiously.

Scripture taken from the King James Version of the Holy Bible

Cover Design by Chase Chandler

Copyright © 2015 Kay Chandler

All rights reserved.

ISBN:

ISBN-13

For

Camille, Keith,

Chad, Stephanie,

Chase and Jennifer

PROLOGUE

PROLOGUE

I was only eight years old the day the church ladies came calling—but the bitter memory left a lingering, raunchy taste in my mouth as sour as a green persimmon.

Mama’s hazel eyes lit up like a neon Packard sign when she peered out the window and saw them coming down the road, all dressed up in their go-to-meeting clothes. She spat on her fingers and dabbed at a smudge on my face before jerking her long auburn hair up into a twist, securing it with a comb. We were about to have company and it was important to Mama that we make a good impression. She yanked off her apron and took a quick glance in the cracked mirror, which hung on a nail above the oak washstand.

“Kiah,” she said, parting my hair with her hand, “when our guests knock on the door, use your manners. Be a gentleman. Invite them in and offer the older lady the rocking chair.” There were only two chairs in our quarters on the Poor Farm—a ladder back and a rickety old rocker Mama salvaged from the dump.

“Well, I reckon they’ll just have to take turns sitting, Mama, since there are three of ’em.” But it wasn’t hard to tell which one was the oldest. Or the meanest. Mrs. Ola Mae Dobbins. She was my Sunday School teacher and I wasn’t fond of the old goat.

I didn’t tell Mama, but the woman didn’t like me from the first day I walked in her class. In fact, I heard her tell her prune-faced husband I was a little buzzard. Or at least, that’s what it sounded like to me at the time, and I was old enough to know a buzzard wasn’t something people admired. I was eleven before I learned from a bully in the schoolyard what she really called me. I found out later being called a buzzard wasn’t the worse thing in the world.

Even now, an indigestible rage regurgitates within my gut as I recall the wounded look on Mama’s face when the ladies said the church elected them to inform us we weren’t welcome in their fellowship. Funny word, “fellowship.” In my young mind, I pictured a big white boat reserved for a few hen-pecked men wearing top hats and morning coats and a bunch of nosey old biddies, all appointed by God to check off the passenger list, before setting sail.

I peeked out from behind Mama’s skirt as Mrs. Ola Mae explained the church’s position. Said the Bible warned against mixing with our kind, being as how I didn’t have a daddy. Tears welled in my eyes as I imagined Mrs. Ola Mae sailing toward heaven’s pearly gates on the big fine Fellow Ship—smirking, as she waved goodbye to those of us who missed the boat.

Mama nodded and said she understood. But I knew she didn’t. And neither did I.

Pivan Falls, Mississippi, 1929

The bitterness inside me festered like a painful boil. Looking back, I reckon it was about two months shy of my seventeenth birthday when I decided to make a dual vow to never show myself inside a church building again, nor allow myself to fall for a dame.

I’ll admit such a vow was akin to making a solemn oath never to eat maggot stew. Wouldn’t happen and I knew it. Still, I didn’t believe in taking chances. To be safe, I stayed far removed from anything with a steeple or anyone wearing a skirt. I make no apologies for being cynical. I had my reasons. I’d learned more about love than I cared to know by witnessing its devastation upon Mama. Though she’d never admit it, I was living proof that reckless love had led her to no good end. I would not be so foolhardy.

Let me be clear. I’m a normal, healthy, red-blooded American male, who isn’t immune to having my head turned by the sight of a good-looking chickadee. But I figured if I was stupid enough to put myself in harm’s way, then I deserved any pain inflicted upon me by hoity-toity church folks or silly, conniving females. How was I to know the prettiest girl in the land of cotton—a parson’s daughter, no less—would move to Mississippi and set her sights on the likes of me? I’d never seen a real live angel until the day Zann Pruitt stood at the front of the class beside our teacher, Mr. Thatcher.

He rapped a gavel on his desk. “Class, I’d like to introduce a new pupil.”

Sweat popped out on my brow. She was prettier than a newborn calf. Little in stature, but not frail looking. Her fine features and bones were sculpted to perfection. Her cheeks had a healthy, rosy glow like a ripened peach and thick, fluttering lashes framed big, ebony orbs. Long raven locks fell in folds on her shoulders like shiny black silk, and the form-fitting calico dresses, which she wore so well, were decked out with rows and rows of colorful rick-rack. No doubt about it, the girl was a cool drink of water to thirsty eyes; yet, I figured if I should suffer such an ailment, boric acid was a much safer remedy.

Arnold Evers stood with his hand raised. “Excuse me, Mr. Thatcher, but if the little lady needs help catching up, I’ll be more than happy to assist. I’m available every Saturday night.” Giggles erupted. I grimaced, knowing the kind of assistance he had in mind, and I could look at her and tell she was

not

that kind of girl. Arnold prided himself on being a ladies man and for reasons I couldn’t understand, the girls did seem to go for him. But why should I care? So what if he was three inches taller than me, had hair the color of autumn wheat, wore dungarees that fit and owned store-bought shirts? It didn’t change the fact he was a low-down rascal.

“Thank you, Arnold,” Mr. Thatcher said, “but looking over her records, I don’t think she’ll need your assistance. Miss Pruitt has excellent marks.”

“Then maybe she can help me. I could sure learn a lot from someone like her.”

The class broke out in thunderous laughter, though I failed to grasp the humor.

She looked at Arnold and smiled. Her voice was soft and melodic. “I thank you for your kindness—”

I bristled. Kindness? Was that what she thought? I likened her naïve remark to that of a biddy telling a chicken hawk, “Thanks for offering me a lift.” If only she knew Arnold Evers the way I knew him.

He ran his fingers through his sleek hair. “Just want to make you feel welcome, ma’am.”

Mr. Thatcher’s brow furrowed. “Have a seat, please, Arnold.”

My heart pounded when Mr. Thatcher led her down the aisle and sat her within arm’s reach of my desk. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the smile fade from her lips as she thumbed through her math book. She raised her hand. “Pardon me, Mr. Thatcher, but it seems your class is ahead of me in mathematics. I fear I may need tutoring to catch up.”

Arnold let out a “hot-diggedy-dog,” and winked. “Don’t forget, I chose first, sugar.”

Mr. Thatcher shot a menacing look his way, but didn’t respond. Seemed to me he should’ve made Arnold stay after school for a month or so, for being such an ignoramus. Instead, Mr. Thatcher made his way back down the aisle and gently laid his hand on my shoulder.

“Miss Pruitt, if you need help, this is your man. Kiah Grave is a math genius.”

I made a futile attempt to focus my gaze on the knothole in the pine flooring. My mouth felt as if it had been swabbed with a cotton boll as I slid down in my desk and snuck a peek.

Zann batted long lashes, glanced at me and smiled. “I’ll keep that in mind.”

My head swelled. Not because Mr. Thatcher called me a genius, but he called me a man. Zann’s man. It wasn’t that I had a hankering to belong to any cockeyed female, because I didn’t, but I can’t deny it was a boost to my ego. She was a pretty thing for sure, but so is a young colt or a freshly furrowed field and as many times as I’ve looked at both, I’ve never been tempted to fall in love with either. Yet, even when I tried to keep my eyes glued on the blackboard, it was impossible not to glimpse the poised frame on the other side of the aisle, since her desk was diagonally across from mine. For fear of being misunderstood, love had nothing to do with it. I still had control over my emotions, even though I seemed to have lost control of my eyes, which kept shifting in her direction against my will. Regardless of how many times I reminded myself not to look her way, it was as futile as reminding a yard dog not to suck eggs.

A real dish—the way she sat with her head held high, her shapely legs crossed at the ankles—but she had a strange habit, which I found most annoying. She’d glide her pencil slowly across her mouth, yet she never gripped it between her teeth. Never. She sort of slid it, playful like, over perfect-shaped pink lips, then she’d tap it lightly against the wooden desk. Why it bothered me, I can’t explain, but I wanted to reach across the aisle, grab that stupid pencil and yell, “What’s wrong with you? Go ahead and sink your teeth into it, or let it be. Stop teasing it.”

I swallowed hard. There was nothing wrong with her, but there was definitely something wrong with a fellow who’d fixate on a wooden pencil until he was ready to turn loose of his senses and make a blubbering idiot of himself. Suppose I really did scream out in class?

I’d remember to ask Mama if insanity ran in the family. I shrugged. What would Mama know about my paternal bloodline, the aristocratic Lancasters, who checked out before I was born? My lip curled at the amusing notion that I could’ve possibly inherited something from my highfalutin ancestors, if nothing but lunacy.

I did my dead-level best to discourage any romantic notions Zann might have, but from the first day she walked into our little two-room school building, she stuck to me like a tick on a hound’s ear. When she slipped me a note in class, I raised my upper lip and snarled. I wanted her to notice I didn’t read it, so I made a show of wadding it up and cramming the paper into the top pocket of my overalls. I glanced over to make sure she saw me. I expected her to be furious. Instead, she flashed those pearly white teeth and her wide eyes transformed into tiny slits, as if she knew I couldn’t wait to get home and smooth out the crumpled note. I’d never met anyone so exasperating.

To complicate matters, her daddy was the Baptist preacher in Pivan Falls. He was also the Methodist preacher. I reckon you might say he was also the Presbyterian preacher, since he was the only preacher for miles around. When anyone in the community married, died, or had need for a man of the cloth, they called on Zann’s father, Parson Pruitt.

Of all the boys in school, I had the least going for me. I was shy, slow to make friends, and I had curls. Yeah, curls. Tight, kinky ringlets that looked like thick wool on an unsheared sheep. What was the girl thinking? Me, a penniless, gangly, curly-haired loser. Not that being poor in 1929 put me in a unique category. There was poor--and

dirt

poor. We were at the bottom of the second category.

I owned two pair of overalls. One, so short the legs barely touched the top of my brogans. The other, Mama bought at a rummage sale for a quarter. The day I tried them on, her jaw dropped. But being the optimist she was, she lifted her brow and said, “Maybe they’re a little large, son, but look on the bright side. There’s growing room in them.”

“You’re right about that, Mama,” I smarted back. “I could grow a nice-sized family in size 38 overalls. The little wife and I could occupy one leg, and there’s ample room in the other leg for half-dozen kiddies.”

Mama paid me no mind. She yanked the straps up until the bib reached my chin. I reckon she figured a fellow with no plans to choose a bride would have no cause to worry about where he’d raise a family. I pulled them off and slung them on the floor.

“Mama,” I growled, “I can’t wear these to school.”

But I did. I didn’t have to be a Harvard scholar to understand I had a serious problem when I showed up wearing my big-man britches and Zann Pruitt continued to follow me around.

She was like fly paper. I couldn’t seem to free myself from her. When she entered the room, my hands got all sweaty and I hassled like an ol’ coon dog who’s trailed his prey ‘til his tongue hangs out. However, it didn’t mean I was ready to change my mind about love. I wasn’t. To look was one thing, but falling in love or getting religion was entirely different.

I had plenty of reasons for feeling as I did and it was all Mama’s fault. Not that she meant to turn me against love, but she did, just the same. She’d lean back in her chair and with a starry-eyed expression, repeat the familiar, grating words.

“My, my, Kiah, I do declare, son, if you ain’t the spittin’ image of Will Lancaster.”

I knew what came next and jerked back to keep her from running her fingers through my hair.

“You have his dark curls, blue eyes and deep dimples. Built like him, too. Long arms, trim waist and broad shoulders. Ah, what a handsome man. Your daddy was such a—”

Hearing her call the man my daddy made me want to puke. Any man who’d skedaddle after bringing a child into the world, leaving it nameless to be ridiculed and labeled by pious snobs wasn’t worth the Mississippi mud caked on the bottom of his shoe. Nevertheless, I supposed with his money and fancy duds, he could cruise into heaven on the big fine Fellow Ship with Mrs. Ola Mae and all her cronies.

Well, I’d prove to all the religious do-gooders that buzzards have wings and can fly same as an eagle. I was bright and I knew it. I had dreams of becoming a Harvard Professor, though I shared my ambitions with no one. After all, who’d believe a poor Mississippi buzzard could soar to such heights?

Although Zann never asked about the man who sired me, I was sure she’d heard the gossip about Mama and me. Yet strangely enough, she treated me like I was good as the next fellow. Maybe, even better. She waited for me before school, after school and at lunch. When I saw she wasn’t going to leave me alone, I quit trying so hard to get rid of her.

Before I knew what was happening, she began to grow on me. Sort of like a seed wart I once had. I tried every remedy in the book to rid myself of the unwanted growth on my hand. Nothing worked. Then one day, I realized I still had the wart, but it didn’t bother me anymore. I’d gotten accustomed to seeing it there. It became as much a part of me as the five fingers on that hand. And that’s how it was with Zann. Without my approval she attached herself to me, but I eventually became accustomed to having her around.

Zann wasn’t only beautiful, she was smart. She never missed a single question on history exams, and there wasn’t a word in the dictionary she couldn’t spell. That’s why I was surprised when she approached me one morning before school with a proposition. It was almost time for the bell, and I’d just walked up to the pump for a drink of water. I was in serious pain. I must have grown three inches overnight. I had on my short overalls and they were so tight they were cutting me in two. If I bent down to drink, I was likely to come up twins. Nevertheless, I was thirsty enough to try it. Should my body divide, I’d let my brother have the girl

and

the overalls, then maybe Mama would see the need to buy me a new pair.

“Hi Kiah,” Zann said in a near whisper, swaying from side to side. Her porcelain-like hands clasped together tightly near her tiny waist.

Relieved that neither I nor my britches had split on the way down, I straightened, and with the back of my hand, wiped water from my lips.

“Whatcha want, Zann?” My left eye twitched when she smiled. My knees knocked. The girl was a picture of everything lovely, balled up and neatly packaged in flesh and blood. I ran my hands through my tousled hair, as she stood batting those thick lashes. My face heated up. I could only imagine how I must look to her, wearing patched overalls, three sizes too small, and a tacky, hand-made shirt with a frayed collar.

Mama did the best she could when she stitched up the unbleached muslin shirt, but a seamstress she was not. I could hardly wait for cooler weather when I could pack away the horrid shirt that made me look like a throwed-away scalawag, and pull out my red flannel store-bought shirt, which made me feel like a man. I swallowed. If only I could be wearing the red flannel at this very moment. I shrugged. Why should I care? I wanted to deny it had anything to do with Zann Pruitt.

“Kiah?” She repeated, her smile fading.

I could see she was fretting over something, the way her brows shot up between her eyes, drooping slightly on either end. When her lower lip quivered, I tried to appear unmoved.