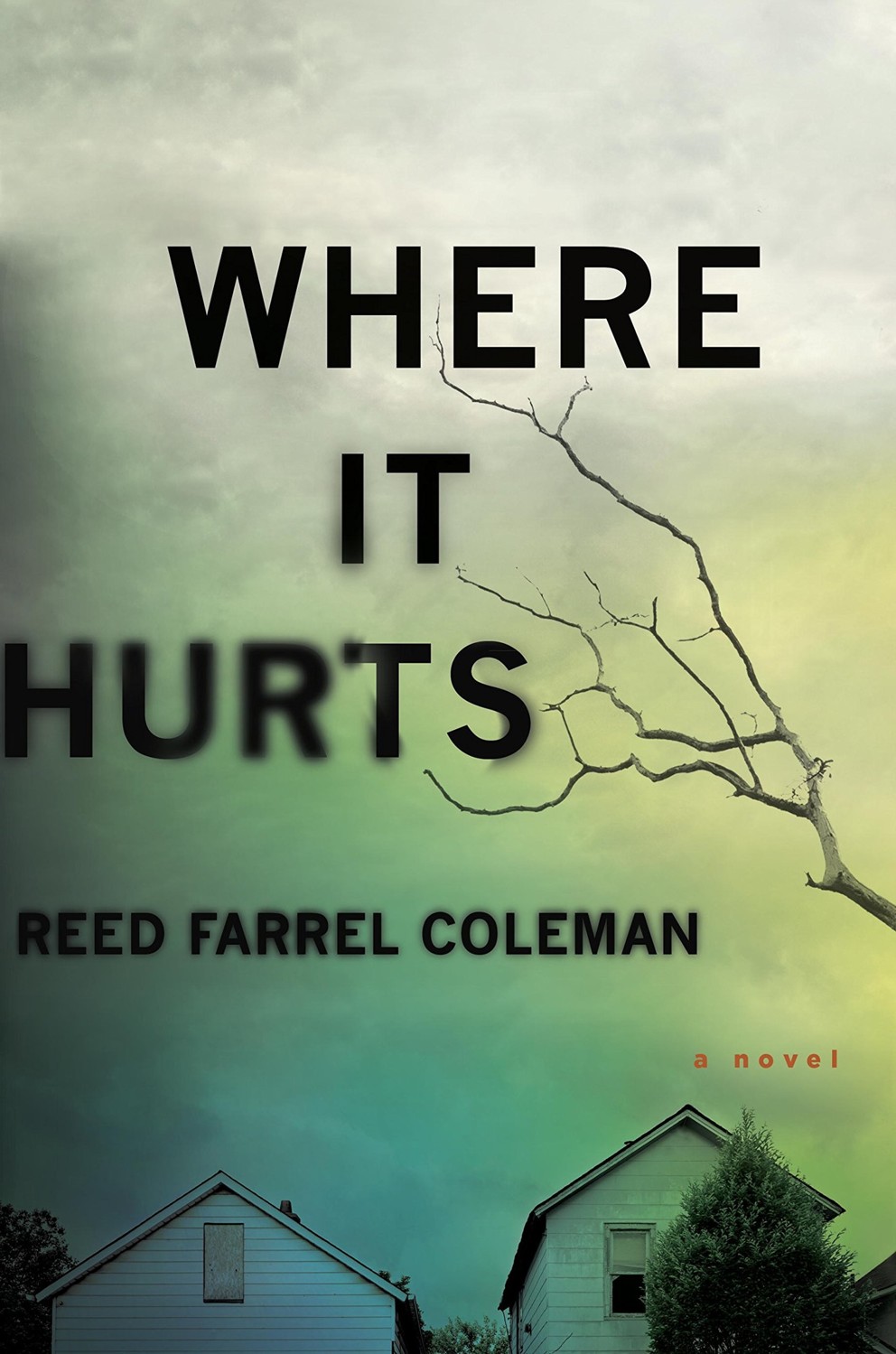

Where It Hurts

Authors: Reed Farrel Coleman

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #United States, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Hard-Boiled, #Private Investigators

ALSO BY REED FARREL COLEMAN

DYLAN KLEIN SERIES

Life Goes Sleeping

Little Easter

They Don’t Play Stickball in Milwaukee

MOE PRAGER SERIES

Walking the Perfect Square

Redemption Street

The James Deans

Soul Patch

Empty Ever After

Innocent Monster

Hurt Machine

Onion Street

The Hollow Girl

JOE SERPE SERIES

Hose Monkey

The Fourth Victim

GULLIVER DOWD SERIES

Dirty Work

Valentino Pier

The Boardwalk

ROBERT B. PARKER’S JESSE STONE

Blind Spot

The Devil Wins

STAND-ALONE NOVELS

Tower

(with Ken Bruen)

Bronx Requiem

(with John Roe)

Gun

Church

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Publishers Since 1838

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright © 2016 by Reed F. Coleman, Inc.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-698-18409-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Coleman, Reed Farrel, date.

Where it hurts : a Gus Murphy novel / Reed Farrel Coleman.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-399-17303-5

I. Title.

PS3553.O47445W48 2016 2015017115

813'.54—dc23

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

For Paul E. Pepe Jr., Evan Lieberman, and Jeff Fisher

—

There is always a cause, but not always a because. And even when there is, the dead are beyond its reach or

caring.

(MONDAY NIGHT)

S

ome people swallow their grief. Some let it swallow them. I guess there’re about a thousand degrees in between those extremes. Maybe a million. Maybe a million million. Who the fuck knows? Not me. I don’t. I’m just about able to put one foot before the other, to breathe again. But not always, not even most of the time. Annie, my wife, I mean, my ex-wife, she let it swallow her whole and when it spit her back up, she was someone else, something else: a hornet from a butterfly. If I was on the outside looking in and not the central target of her fury and sting, I might understand it. I might forgive it. I tell myself I would. But I’d have to forgive myself first. I might as well wish for Jesus to reveal himself in my sideview mirror or for John Jr. to come back to us. At the moment, my wishes were less ambitious ones. I wished for the 11:38 to Ronkonkoma to be on time. I should have wished for it to be early.

I checked the dashboard clock as I pulled into the hotel courtesy van parking spot out in front of the Dunkin’ Donuts shop at the station.

11:30,

eight

minutes

to

spare

. But spare time was empty time and I had come to dread it because empty was pretty much all I was anymore. Two years steeped in emptiness and I still didn’t know how to fill it up. My shrink, Dr. Rosen, says not to try, that I should let myself

fully experience the void. That if I don’t give myself permission to feel the depth of the abyss, the slipperiness of its walls, I’ll never climb out. The thing is, you have to want to climb out, don’t you? Even a spare minute was chance enough to relive the last two years. Took forever to live it. Takes only seconds to live it again. I had tried filling in the fissures, cracks, and cavities with wondering, wondering about the trick of time. That got me about as far as wishing. Nowhere.

I stepped out of the van into the chill night. My breath turned to heaving clouds of smoke as cold as God’s love.

Hail

Mary

,

full

of

shit

,

the Lord

is

with

thee

,

not

me

. I didn’t really want coffee. No man who lives for sleep as I do wants coffee. But I had to sustain my waking trance until six a.m. Then I could turn the van keys over to Fredo and fall into my cool sheet-and-quilt-covered solace. When I was on the job, it was different. Everything was different. I liked the world then and the people in it. Liked the buzz of caffeine. Yeah, that was me once, the cop in a doughnut shop, reinforcing stereotypes. Now I was just occupying my mind, doing something, anything not to sit in the van marking time.

Aziza, the mocha-skinned Pakistani girl behind the counter, nodded at me. Smiled a gap-toothed smile. She no longer asked what I wanted.

Small coffee. Half-and-half. Two Sweet’N Lows.

She made it up for me. Put it on the counter. She no longer gave me the change when I paid. She dropped the change in the paper tip cup with the other careless pennies, quarters, dimes, and nickels. I liked Aziza because she expected nothing of me beyond our routine. We danced our nightly dance and then went back to being strangers. She didn’t expect me to put the pain behind me or to bravely get on with my life.

Khalid, the night manager, a fleshy man with shark eyes and a suspicious face, stared at me as he always did. It was as if he could smell the taint on me. He didn’t like me in the shop. Thought I might sully the place with my taint, or maybe that wasn’t it at all.

I got back to the van as the 11:38 pulled into Ronkonkoma. In the eight minutes that had passed, the usual crowd had descended upon the station. Parents in double-parked SUVs, waiting to pick up their kids.

Bored-looking husbands unhappy at being dragged off their sofas into the cold night because their wives felt like doing Broadway with the girls. Cabbies outside their cars, their flannel-shirted bellies flopping over their belt lines, smoking cigarettes, talking shit to each other. I placed the coffee inside the van and took out my Paragon Hotel placard on which the words W

ESTEX

T

ECHNICAL

were written in black marker.

I was scheduled to pick up a party of three from Westex and bring them back to the Paragon. The Paragon Hotel of Bohemia, New York, was paragon of nothing so much as proximity, proximity to Long Island MacArthur Airport. And MacArthur Airport, an airport of three airlines, was nothing so much as an unfulfilled promise, the little airport that couldn’t. The Paragon was a way station, a place to pass through on the way to or from the airport. There was the occasional foreign tourist who’d fixated on the room rate instead of the distance to New York City or had neglected to convert kilometers into miles.

The three Westex guys were what I expected, what most of my passengers were: tired, hungry, distracted. When I got back into the van after loading their bags into the rear, all of them were busy with their phones or tablets. They kind of grunted to themselves and one another. I was glad of that, happy to be ignored. I had trouble with the chatty ones, the ones who wanted to be your pal. When I was on the job, I understood nervous chatter because the uniform made people nervous. I also had empathy for the compulsively polite. Not anymore. Who in their heart of hearts really wanted to be the van driver’s buddy? It was all so much bullshit, a way to pass time from point to point. I was in on the lie of passing time, so I never spoke first. Never asked where anyone was from. Never asked if they had enjoyed the city. Never asked what they did for a living, or about their families. Never asked where they were headed. I knew where they were headed. We were all headed there, eventually.

I put the van in drive, looked in my sideview for oncoming cars or the Second Coming. And not seeing either, I pulled the wheel hard left and made a sweeping U-turn west onto Railroad Avenue. As we went, I sipped at my unwanted coffee, thinking of my dead son.