Where Wizards Stay Up Late (27 page)

The USPS, like AT&T earlier, never really broke free of the mindset guarding its traditional business, probably because both were monopolistic entities. Eventually the U.S. Justice Department, the FCC, and even the Postal Rate Commission opposed any significant government role in e-mail services, preferring to leave them to the free market.

No issue was ever too small for long discussion in the MsgGroup. The speed and ease of the medium opened vistas of casual and spontaneous conversation. It was apparent by the end of the decade to people like Licklider and Baran that a revolution they had helped start was now under way.

“Tomorrow, computer communications systems will be the rule for remote collaboration” between authors, wrote Baran and UC Irvine's Dave Farber. The comments appeared in a paper written jointly, using e-mail, with five hundred miles between them. It was “published” electronically in the MsgGroup in 1977. They went on: “As computer communication systems become more powerful, more humane, more forgiving and above all, cheaper, they will become ubiquitous.” Automated hotel reservations, credit checking, real-time financial transactions, access to insurance and medical records, general information retrieval, and real-time inventory control in businesses would all come.

In the late 1970s, the Information Processing Techniques Office's final report to ARPA management on the completion of the

ARPANET

research program concluded similarly: “The largest single surprise of the

ARPANET

program has been the incredible popularity and success of network mail. There is little doubt that the techniques of network mail developed in connection with the

ARPANET

program are going to sweep the country and drastically change the techniques used for intercommunication in the public and private sectors.”

To members of the MsgGroup, electronic mail was as engrossing as a diamond held to the light. MsgGroup members probed every detail. They were junkies for the technology. The issue of time and date stamps, for example, was classic. “My boss's boss's boss complains of the ravings of the late-nighters,” someone said. “He can tell from the time stamp (and the sender's habits) how seriously to take the message.”

“Perhaps we should time-stamp with the phase of the moon in addition to date and time,” said another. (Before long someone wrote an e-mail program that did just that.)

“I really like seeing an accurate time stamp,” said someone else. “It's nice to be able to unravel the sequence of comments received in scrambled order.”

“Some people use it blatantly as a kind of one-upmanship. âI work longer hours than you do.'”

MsgGroup members could argue about anything. There were times when you'd swear you had just dropped in on a heated group of lawyers, or grammarians, or rabbis. Strangers fell casually into the dialogue or, as someone called it, the “polylogue.” As the regulars became familiar to one another, fast friendships were cemented, sometimes years before people actually met. In many ways the

ARPANET

community's basic values were traditionalâfree speech, equal access, personal privacy. However, e-mail also was uninhibiting, creating reference points entirely its own, a virtual society, with manners, values, and acceptable behaviorsâthe practice of “flaming,” for exampleâstrange to the rest of the world.

Familiarity in the MsgGroup occasionally bred the language of contempt. The first real “flaming” (a fiery, often abusive form of dialogue) on the

ARPANET

had flared up in the mid-1970s. The medium engendered rash rejoiners and verbal tussles. Yet heavy flaming was kept relatively in check in the MsgGroup, which considered itself civilized. Stefferud almost single-handedly and cool-headedly kept the group together when things got particularly raucous and contentious. He slaved to keep the MsgGroup functioning, parsing difficult headers when necessary or smoothing out misunderstandings, making sure the group's mood and its traffic never got too snarly. About the worst he ever said, when beset by technical problems, was that some headers had “bad breath.”

By comparison, there was a discussion group next door (metaphorically speaking), called Header People, reputed to be an inferno. “We normally wear asbestos underwear,” said one participant. Based at MIT, Header People had been started by Ken Harrenstien in 1976. The group was unofficial, but more important, it was unmoderated (meaning it had no Stefferud-like human filter). Harrenstien had set out to recruit at least one developer from every kind of system on the

ARPANET,

and in no time the conflicts in Header People raised the debate over headers to the level of a holy war before flaming out. “A bunch of spirited sluggers,” said Harrenstien, “pounding an equine cadaver to smithereens.” The two mail-oriented groups overlapped considerably; even in civilized Msg-Group company, tempers flared periodically. The acidic attacks and level of haranguing unique to on-line communication, unacceptably asocial in any other context, was oddly normative on the

ARPANET

. Flames could start up at any time over anything, and they could last for one message or one hundred.

The

FINGER

controversy, a debate over privacy on the Net, occurred in early 1979 and involved some of the worst flaming in the MsgGroup's experience. The fight was over the introduction, at Carnegie-Mellon, of an electronic widget that allowed users to peek into the on-line habits of other users on the Net. The

FINGER

command had been created in the early 1970s by a computer scientist named Les Earnest at Stanford's Artificial Intelligence Lab. “People generally worked long hours there, often with unpredictable schedules,” Earnest said. “When you wanted to meet with some group, it was important to know who was there and when the others would likely reappear. It also was important to be able to locate potential volleyball players when you wanted to play, Chinese-food freaks when you wanted to eat, and antisocial computer users when it appeared that something strange was happening on the system.”

FINGER

didn't allow you to read someone else's messages, but you could tell the date and time of the person's last log-on and when last he or she had read mail. Some people had a problem with that.

In an effort to respect privacy, Ivor Durham at CMU changed the

FINGER

default setting; he added a couple of bits that could be turned on or off, so the information could be concealed unless a user chose to reveal it. Durham was flamed without mercy. He was called everything from spineless to socially irresponsible to a petty politician, and worseâbut not for protecting privacy. He was criticized for monkeying with the openness of the network.

The debate began as an internal dialogue at CMU but was leaked out onto the

ARPANET

by Dave Farber, who wanted to see what would happen if he revealed it to the outer world. The ensuing flame-fest consumed more than 400 messages.

At the height of the

FINGER

debate, one person quit the Msg-Group in disgust over the flaming. As with the Quasar debate, the

FINGER

controversy ended inconclusively. But both debates taught users greater lessons about the medium they were using. The speed of electronic mail promoted flaming, some said; anyone hot could shoot off a retort on the spot, and without the moderating factor of having to look the target in the eye.

By the end of the decade, the MsgGroup's tone, which had begun stiffly, was an expansive free-for-all. Stefferud always tried to get newcomers to introduce themselves electronically when they joined the group; when leaving, some bid farewell only to turn up again later at other sites; only one or two people huffed off, quite ceremoniously, over a flame-fest or some other perceived indignity.

One of the MsgGroup's eminent statesmen, Dave Crocker, sometimes probed the Net with a sociologist's curiosity. One day, for example, he sent a note to approximately 130 people around the country at about five o'clock in the evening, just to see how fast people would get the message and reply. The response statistics, he reported, were “a little scary.” Seven people responded within ninety minutes. Within twenty-four hours he had received twenty-eight replies. Response times and numbers on that order may seem hardly noteworthy in a culture that has since squared and cubed its expectations about the speed, ease, and reach of information technology. But in the 1970s “it was an absolutely astonishing experience,” Crocker said, to have gotten so many replies, so quickly, so easily, as that.

On April 12, 1979, a rank newcomer to the MsgGroup named Kevin MacKenzie anguished openly about the “loss of meaning” in this electronic, textually bound medium. Unquestionably, e-mail allowed a spontaneous verbal exchange, but he was troubled by its inability to convey human gestures, facial expressions, and tone of voiceâall of which come naturally when talking and express a whole vocabulary of nuances in speech and thought, including irony and sarcasm. Perhaps, he said, we could extend the set of punctuation in e-mail messages. In order to indicate that a particular sentence is meant to be tongue-in-cheek, he proposed inserting a hyphen and parenthesis at the end of the sentence, thus: -).

MacKenzie confessed that the idea wasn't entirely his; it had been sparked by something he had read on a different subject in an old copy of

Reader's Digest.

About an hour later, he was flamed, or rather, singed. He was told his suggestion was “naive but not stupid.” He was given a short lecture on Shakespeare's mastery of the language without auxiliary notation. “Those who will not learn to use this instrument well cannot be saved by an expanded alphabet; they will only afflict us with expanded gibberish.” What did Shakespeare know? ;-) Emoticons and smileys :-), hoisted by the hoi polloi no doubt, grew in e-mail and out into the iconography of our time.

It's a bit difficult to pinpoint when or whyâperhaps it was exhaustion, perhaps there were now too many new players in the MsgGroupâbut by the early 1980s, note by note, the orchestra that had been performing magnificently and that had collectively created e-mail over a decade, began abandoning the score, almost imperceptibly at first. One key voice would fade here, another would drift off there. Instead of chords, white noise seemed to gradually overtake the MsgGroup.

In some sense it didn't matter. The dialogue itself in the Msg-Group had always been more important than the results. Creating the mechanisms of e-mail mattered, of course, but the MsgGroup also created something else entirelyâa community of equals, many of whom had never met each other yet who carried on as if they had known each other all their lives. It was the first place they had found something they'd been looking for since the

ARPANET

came into existence. The MsgGroup was perhaps the first virtual community.

The romance of the Net came not from how it was built or how it worked but from how it was used. By 1980 the Net was far more than a collection of computers and leased lines. It was a place to share work and build friendships and a more open method of communication. America's romance with the highway system, by analogy, was created not so much by the first person who figured out how to grade a road or make blacktop or paint a stripe down the middle but by the first person who discovered you could drive a convertible down Route 66 like James Dean and play your radio loud and have a great time.

A Rocket on Our Hands

Bob Kahn left BBN and went to work for Larry Roberts in 1972. He had deferred his arrival in Washington for a year to stay in Cambridge and plan the ICCC demonstration. Having spent six uninterrupted years focused on computer networking, he was now ready to make a clean break. He did not want to run a network project. So he and Roberts agreed that Kahn would set up a new program in automated manufacturing techniques. But Congress canceled the project before Kahn arrived. By now, ARPA had been changed to DARPAâthe Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. As Kahn once put it, the

D

had always been there, but now it was no longer silent. The name

ARPANET

remained.

With the manufacturing project gone, Kahn was called back to the field in which he had grown expert. But he wanted to work on the newest experiments.

The early 1970s were a time of intense experimentation with computer networking. A few people were beginning to think about new kinds of packet networks. The basic principles of packet-switching were unlikely to be improved upon dramatically. And the protocols, interfaces, and routing algorithms for handling messages were growing more refined. One area still to explore, however, was the medium over which data traveled. The existing AT&T web of telephone lines had been the obvious first choice. But why not make a wireless network by transmitting data packets “on the air” as radio waves?

In 1969, before Bob Taylor had left ARPA, he set up funding for a fixed-site radio network to be built at the University of Hawaii. It was designed by a professor named Norm Abramson and several colleagues. They constructed a simple system using radios to broadcast data back and forth among seven computers stationed over four islands. Abramson called it

ALOHA

.

The

ALOHANET

used small radios, identical to those used by taxicabs, sharing common frequency instead of separate channels. The system employed a very relaxed protocol. The central idea was to have each terminal transmit whenever it chose to. But if the data collided with somebody else's transmission (which happened when there was a lot of traffic), the receivers wouldn't be able to decode either transmission properly. So if the source radio didn't get an acknowledgment, it assumed the packet had gotten garbled; it retransmitted the packet later at a random interval. The

ALOHA

system was like a telephone service that told you, after you tried to speak, and not until then, that the line was busy.

Roberts and Kahn liked the general idea of radio links between computers. Why not do something still more challenging: devise small portable computer “sites” carried around in vehicles or even by hand, linked together in a packet-switching network? In 1972 Roberts outlined the scheme. He envisioned a network in which a central minicomputer situated in a powerful radio station would communicate with smaller mobile computer sites. Roberts asked SRI to study the problem and work out a practical system.

The concept of mobile computer sites held obvious appeal to the Army. Battlefield computers installed in vehicles or aircraftâmoving targetsâwould be less vulnerable and more useful than fixed installations. Still, destruction of the single most crucial elementâthe stationary master computer in a centralized systemâwould take out a whole network. The need to defend against that danger was what had led Paul Baran to devise distributed networks in the first place. So from the standpoint of survivability and easy deployment, the packet radio network was conceived as a wireless version of the

ARPANET

, distributed rather than centralized. Over the years, the packet radio program was deployed at a handful of military sites, but technical problems made it expensive, and it was eventually phased out.

The limited range of radio signals made it necessary for packet-radio networks to use relay sites no more than a few dozen miles apart. But a link above the earth would have no such constraints. Such a relay would “see” almost an entire hemisphere of the earth. While overseeing the packet-radio projects, Kahn began to think about networks linked by satellites accessible over broad domainsâto and from ships at sea, remote land-based stations, and aircraft flying almost anywhere in the world.

By the early 1970s, many communications satellitesâmost of them militaryâwere in orbit. Appropriately equipped, such a satellite could serve as a relay for communication. With the huge distances involved in satellite communications, signals would be delayed. The average trip for a packet to its destination would take about one third of a second, several times longer than host-to-host delays on the

ARPANET

. As a result, packet-satellite networks would be slow.

Still, the idea that packet-switched networks and their attached computers could be linked by radio waves bounced from a satellite was appealing, not only to the American government but also to Europeans, because transatlantic terrestrial circuits at the time were expensive and prone to error. The satellite network was dubbed

SATNET

. Researchers in the United States were joined by British and Norwegian computer scientists, and before long satellite links were established to Italy and Germany as well. For a while,

SATNET

did well. In time, however, the phone company upgraded its transatlantic lines from copper to high-speed fiber-optic cable, eliminating the need for the more complicated

SATNET

link.

The technical lessons of radio and satellite experiments were less significant than the broader networking ideas they inspired. It was obvious there would be more networks. Several foreign governments were building data systems, and a growing number of large corporations were starting to develop networking ideas of their own. Kahn began wondering about the possibility of linking the different networks together.

The problem first occurred to him as he was working on the packet-radio project in 1972. “My first question was, âHow am I going to link this packet-radio system to any computational resources of interest?'” Kahn said. “Well, my answer was, âLet's link it to the

ARPANET

,' except that these were two radically different networks in many ways.” The following year, another ARPA effort, called the Internetting Project, was born.

By the time of the 1972 ICCC demonstration in Washington, the leaders of several national networking projects had formed an International Network Working Group (INWG), with Vint Cerf in charge. Packet-switching network projects in France and England were producing favorable results. Donald Davies's work at the U.K.'s National Physical Laboratory was coming along splendidly. In France, a computer scientist named Louis Pouzin was building Cyclades, a French version of the

ARPANET

. Both Pouzin and Davies had attended the ICCC demonstration in Washington. “The spirit after ICCC,” said Alex McKenzie, BBN's representative to the INWG, “was, âWe've shown that packet-switching really works nationally. Let's take the lead in creating an international network of networks.'”

Larry Roberts was enthusiastic about INWG because he wanted to extend the reach of the

ARPANET

beyond the DARPA-funded world. The British and the French were equally excited about expanding the reach of their national research networks as well. “Developing network-interconnection technology was a way to realize that,” said McKenzie. The INWG began pursuing what they called a “Concatenated Network,” or

CATENET

for short, a transparent interconnection of networks of disparate technologies and speeds.

The collaboration that Bob Kahn would characterize years later as the most satisfying of his professional career took place over several months in 1973. Kahn and Vint Cerf had first met during the weeks of testing at UCLA in early 1970, when they had forced the newborn

ARPANET

into catatonia by overloading the IMPs with test traffic. They had remained close colleagues, and now both were thinking extensively about what it would take to create a seamless connection among different networks. “Around this time,” Cerf recalled, “Bob started saying, âLook, my problem is how I get a computer that's on a satellite net and a computer on a radio net and a computer on the

ARPANET

to communicate uniformly with each other without realizing what's going on in between?'” Cerf was intrigued by the problem.

Sometime during the spring of 1973, Cerf was attending a conference at a San Francisco hotel, sitting in the lobby waiting for a session to start when he began doodling out some ideas. By now he and Kahn had been talking for several months about what it would take to build a network of networks, and they had both been exchanging ideas with other members of the International Network Working Group. It occurred to Cerf and Kahn that what they needed was a “gateway,” a routing computer standing between each of these various networks to hand off messages from one system to the other. But this was easier said than done. “We knew we couldn't change any of the packet nets themselves,” Cerf said. “They did whatever they did because they were optimized for that environment.” As far as each net was concerned, the gateway had to look like an ordinary host.

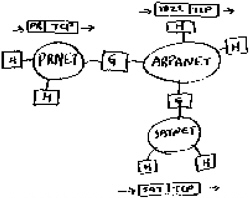

While waiting in the lobby, he drew this diagram:

Reproduction of early Internet design ideas

“Our thought was that, clearly, each gateway had to know how to talk to each network that it was connected to,” Cerf said. “Say you're connecting the packet-radio net with the

ARPANET

. The gateway machine has software in it that makes it look like a host to the

ARPANET

IMPs. But it also looks like a host on the packet-radio network.”

With the notion of a gateway now defined, the next puzzle was packet transmission. As with the

ARPANET

, the actual path the packets traveled in an internet should be immaterial. What mattered most was that the packets arrive intact. But there was a vexing problem: All these networksâpacket radio,

SATNET

, and the

ARPANET

âhad different interfaces, different maximum packet sizes, and different transmission rates. How could all those differences be standardized in order to shuttle packets among networks? A second question concerned the reliability of the networks. The dynamics of radio and satellite transmission wouldn't permit reliability that was so laboriously built into the

ARPANET

. The Americans looked to Pouzin in France, who had deliberately chosen an approach for Cyclades that required the hosts rather than the network nodes to recover from transmission errors, shifting the burden of reliability on to the hosts.

It was clear that the host-to-host Network Control Protocol, which was designed to match the specifications of the

ARPANET

, would have to be replaced by a more independent protocol. The challenge for the International Network Working Group was to devise protocols that could cope with autonomous networks operating under their own rules, while still establishing standards that would allow hosts on the different networks to talk to each other. For example,

CATENET

would remain a system of independently administered networks, each run by its own people with its own rules. But when time came for one network to exchange data with, say, the

ARPANET

, the internetworking protocols would operate. The gateway computers handling the transmission couldn't care about the local complexity buried inside each network. Their only task would be to get packets through the network to the destination host on the other side, making a so-called end-to-end link.

Once the conceptual framework was established, Cerf and Kahn spent the spring and summer of 1973 working out the details. Cerf presented the problem to his Stanford graduate students, and he and Kahn joined them in attacking it. They held a seminar that concentrated on the details of developing the host-to-host protocol into a standard allowing data traffic to flow across networks. The Stanford seminar helped frame key issues, and laid the foundation for solutions that would emerge several years later.

Cerf frequently visited the DARPA offices in Arlington, Virginia, where he and Kahn discussed the problem for hours on end. During one marathon session, the two stayed up all night, alternately scribbling on Kahn's chalkboard and pacing through the deserted suburban streets, before ending up at the local Marriott for breakfast. They began collaborating on a paper and conducted their next marathon session in Cerf's neighborhood, working straight through the night at the Hyatt in Palo Alto.

That September, Kahn and Cerf presented their paper along with their ideas about the new protocol to the International Network Working Group, meeting concurrently with a communications conference at the University of Sussex in Brighton. Cerf was late arriving in England because his first child had just been born. “I arrived in midsession and was greeted by applause because word of the birth had preceded me by e-mail,” Cerf recalled. During the Sussex meeting, Cerf outlined the ideas he and Kahn and the Stanford seminar had generated. The ideas were refined further in Sussex, in long discussions with researchers from Davies'and Pouzin's laboratories.