Which Way to the Wild West? (4 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

Eight-year-old Enrique Esparza was sleeping in a small room in the church at the Alamo. He was jolted awake by a blast of gunfire. “It was so dark that we couldn't see anything,” he remembered.

“Gregorio, the soldiers have jumped the wall,” Enrique's mother said to his father. “The fight's begun.”

Enrique watched his father get up, grab his gun, and run out to join the battle. “I never saw him again,” Enrique said.

E

nrique and his mother, and about fifteen other women and children, huddled in the corners of the room as the battle for the Alamo grew louder. “We could hear the Mexican officers shouting to the men,” Enrique said, “and the men were fighting so close that we could hear them strike each other.”

nrique and his mother, and about fifteen other women and children, huddled in the corners of the room as the battle for the Alamo grew louder. “We could hear the Mexican officers shouting to the men,” Enrique said, “and the men were fighting so close that we could hear them strike each other.”

Susanna Dickinson was in a nearby room, clutching her baby daughter, wondering how the fight was going. “The struggle lasted more than two hours when my husband rushed into the church where I was with my child,” she said.

“Great God, Sue, the Mexicans are inside our walls!” shouted Almeron Dickinson. “All is lost! If they spare you, save my child.”

Almeron was rightâall was lost. By 6:30 that morning, the badly outnumbered Texans were forced to surrender. Santa Anna's soldiers killed all 183 Texas soldiersâstabbing many of them with bayonets after they had surrendered.

Later that March, Mexican soldiers defeated another small American army near the town of Goliad, Texas. About four hundred Americans were taken prisoner. Following Santa Anna's orders, Mexican soldiers marched the prisoners to an open field, shot and bayoneted all of them, and set the bodies on fire.

Enraged Texans promised payback. As one young soldier in the Texas army explained: “The boys were continually talking about the butchery at the Alamo and the slaughter at Goliad; and vowing to avenge the cold-blooded murder of their countrymen.”

T

he job of getting revenge belonged to the volunteers of the Texas armyâabout eight hundred men under the command of Sam Houston. Some doubted that Houston was the right man for the job. While serving as governor of Tennessee a few years back, he had quit suddenly, refusing to give a reason. He had gone to live with the Cherokees, who soon nicknamed him “Big Drunk” (he was six foot two, and often drunk).

he job of getting revenge belonged to the volunteers of the Texas armyâabout eight hundred men under the command of Sam Houston. Some doubted that Houston was the right man for the job. While serving as governor of Tennessee a few years back, he had quit suddenly, refusing to give a reason. He had gone to live with the Cherokees, who soon nicknamed him “Big Drunk” (he was six foot two, and often drunk).

On the plus side, Houston had the ability to remain cool under pressure. And he had a good plan. He began retreating east across Texas, forcing Santa Anna's larger army to chase him two hundred miles. All the while, he watched and waited for the perfect moment to turn and strike.

Houston saw his opportunity near the San Jacinto River on April 21, 1836. “Let us fight fast and hard,” he told his men. “We must win or die.” The Texans charged forward shouting, “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!”

Sam Houston

The attack surprised the entire Mexican army, especially its commander. “I was in a deep sleep when I was awakened by the firing and noise,” confessed Santa Anna. He jumped up from his nap, put on his red slippers, stepped out of his tentâand immediately burst into a panic.

“I saw His Excellency running about in the utmost excitement, wringing his hands, and unable to give an order,” recalled a Mexican officer.

The Texans won the battle in just eighteen minutes. And they did remember the Alamo and Goliadâmaybe too well. It took Houston's officers a while to get the Texans to stop killing Mexican soldiers. When it was all over, nearly six hundred Mexicans were dead, compared with only nine Texans.

Texas soldiers caught Santa Anna (he was trying to escape disguised as a Mexican private), and the Mexican leader agreed to pull his troops out of Texas. So that was thatâTexas had its independence. Some Texans were hoping to join the United States, but for now Texas was an independent country. We'll keep an eye on the situation.

Meanwhile, since we're speaking of land that was not yet part of the United States â¦

I

t was a busy week for Narcissa Prentiss. This young schoolteacher from a small New York town got married on February 18, 1836. The next day, she and her husband, Marcus Whitman, set out for their new home in the Oregon Countryâon the other side of the continent.

t was a busy week for Narcissa Prentiss. This young schoolteacher from a small New York town got married on February 18, 1836. The next day, she and her husband, Marcus Whitman, set out for their new home in the Oregon Countryâon the other side of the continent.

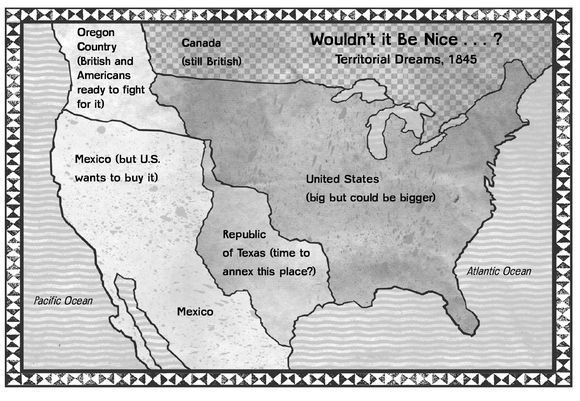

The Oregon Country (the area that now makes up Oregon, Washington, and Idaho) was a huge section of land claimed by both Great Britain and the United States. Both basically said,

I saw it first!

But aside from a few mountain men, no one from Britain or the United States was actually living there. The Whitmans were about to help change that. Their plan was to settle in Oregon and work as missionaries, teaching Christianity to the Walla Walla, Spokane, Nez Perce, and other Native Americans of the region.

I saw it first!

But aside from a few mountain men, no one from Britain or the United States was actually living there. The Whitmans were about to help change that. Their plan was to settle in Oregon and work as missionaries, teaching Christianity to the Walla Walla, Spokane, Nez Perce, and other Native Americans of the region.

In her journal Narcissa called the trip to Oregon “an unheard of journey for females.” She was right. No American woman had ever made this 2,400-mile trek across the Great Plains and over the Rocky Mountains.

As if it were not going to be difficult enough, Narcissa found out at the last second that she and her husband would be traveling with two other missionaries: Henry Spalding and his new wife, Eliza. Henry had asked Narcissa to marry him a few years before, and she had turned him down. He was still bitter about it. So Narcissa knew there would be some awkward moments as the two couples shared a tent for months on their way west.

Luckily, the challenges of the trip kept everyone pretty busy. Buzzing clouds of mosquitoes and fleas surrounded the couples as their wagons bounced across the plains. There were no trees, which

meant no shade from the burning sun, and no wood to make fires. In a letter to her sister, Harriet, and brother, Edward, Narcissa explained how they managed to cook:

meant no shade from the burning sun, and no wood to make fires. In a letter to her sister, Harriet, and brother, Edward, Narcissa explained how they managed to cook:

“Our fuel for cooking ⦠has been dried buffalo dung. We now find plenty of it and it answers a very good purpose, similar to the kind of coal used in Pennsylvania. I suppose Harriet will make a face at this, but if she was here she would be glad to have her supper cooked at any rate.”

Narcissa Whitman

Their food was mainly buffalo meat, which everyone got sick of after a few weeks. “I thought of Mother's bread and butter many times,” Narcissa wrote. The only really dangerous moment came when Eliza's horse took a wrong step. “Yesterday my horse became unmanageable in consequence of stepping into a hornets' nest,” Eliza explained. She was thrown from the horse, but that wasn't the worst part. “My foot remained a moment in the stirrup, and my body dragged some distance,” she said.

You had to be tough to cross the continent, and Eliza obviously wasâshe was back on the trail the next day.

After six long months of traveling, the Whitmans and Spaldings reached the Oregon Country. We'll check back with them later. For now, the important thing to know is that their journey helped show Americans that women and families could travel safely to Oregon. The route they had taken became known as the Oregon Trail. And over the next few years, thousands of families set out on the trail, hoping to claim a piece of rich Oregon farmland.

B

y 1840 Americans knew about the Rocky Mountains from mountain men and had heard all about New Mexico from traveling merchants. Settlers in Texas and Oregon sent back letters describing land that was fertile and cheap. Many Americans began to think,

Wouldn't it be nice if all that land were ours?

y 1840 Americans knew about the Rocky Mountains from mountain men and had heard all about New Mexico from traveling merchants. Settlers in Texas and Oregon sent back letters describing land that was fertile and cheap. Many Americans began to think,

Wouldn't it be nice if all that land were ours?

Lots of them believed it should be. Some were convinced that God wanted it that wayâthat it was God's plan to have the American style of democracy spread across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. This idea was summed up by the journalist John O'Sullivan: “The American claim is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty.”

The phrase

manifest destiny

soon became famous (

manifest

means “clear to see” or “obvious”). O'Sullivan was saying that it was clearly the destiny of the United States to spread from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Was he right? James K. Polk thought so.

manifest destiny

soon became famous (

manifest

means “clear to see” or “obvious”). O'Sullivan was saying that it was clearly the destiny of the United States to spread from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Was he right? James K. Polk thought so.

W

hen leaders of the Democratic Party met to choose a presidential candidate in 1844, they couldn't agree on anyone they really liked. So they decided to compromise on someone they sort of likedâa former Tennessee governor named James K. Polk.

hen leaders of the Democratic Party met to choose a presidential candidate in 1844, they couldn't agree on anyone they really liked. So they decided to compromise on someone they sort of likedâa former Tennessee governor named James K. Polk.

The leaders of the Whig Partyâthe other major political party in the United States at that timeâwere thrilled to be running against this guy. The Whigs' campaign motto was “Who is James K. Polk?”

He may not have been too famous, but Polk was very clear about

what he would do if elected. A strong believer in manifest destiny, Polk insisted that the United States should immediately annex Texas (make it part of the United States, in other words).

Then,

he said,

we should force Great Britain to give up its claims to Oregon. Then we'll buy the rest of the West from Mexico.

what he would do if elected. A strong believer in manifest destiny, Polk insisted that the United States should immediately annex Texas (make it part of the United States, in other words).

Then,

he said,

we should force Great Britain to give up its claims to Oregon. Then we'll buy the rest of the West from Mexico.

These popular ideas helped Polk win a close election (at forty-nine, he was the youngest president to be elected up to that point). He took over as president in March 1845, getting right to work on his plans to expand the United States. In fact, he worked so quickly that in just a few days he nearly started two wars.

First the United States annexed Texas, which brought cheers from Texas and howls of anger from the Mexican capital. Many Mexicans still thought of Texas as part of their country, and they considered the American annexation a cause for war.

James K. Polk?

British leaders, meanwhile, refused Polk's demands that they give up claims to Oregon. The British government started making threats and preparing to fight.

Polk's reply? He was ready to fight both countries at once.

Other books

Another Rib by Marion Zimmer Bradley, Juanita Coulson

There Was a Little Girl: The Real Story of My Mother and Me by Brooke Shields

Tales Of Lola The Black by A.J. Martinez

House of Ashes by Monique Roffey

Chase (ChronoShift Trilogy) by Mason, Zack

Rocked in the Dark by Clara Bayard

THREE DROPS OF BLOOD by Michelle L. Levigne

Jordan (Season Two: The Ninth Inning #5) by Lindsay Paige, Mary Smith

Rapids by Tim Parks

The Archived by Victoria Schwab