Whiskey Bottles and Brand-New Cars (26 page)

Read Whiskey Bottles and Brand-New Cars Online

Authors: Mark Ribowsky

That

was the Wallace with whom Van Zant related. “To me,” Ed King says, “Ronnie was a proud, working-class southern man, and George Wallace represented proud, working-class southern people. To Ronnie, Wallace was not just a man who wouldn't let blacks into a college, he was a man who spoke for poor, uneducated people who didn't have a voice. It's right there in [âSweet Home Alabama'].” Still, it was never easy to split hairs when it came to Wallace. The “Gov'nor” so loved the song that when Skynyrd and the Charlie Daniels Band played a gig in Tuscaloosa, Wallace appeared on stage to present Skynyrd with plaques making them honorary lieutenant colonels in the Alabama State Militiaâanother symbol of racial grievance, since the militia had imposed martial law during the civil rights marches. Rather than steering clear of the “honor,” they eagerly jumped at the chance to be deputized. Indeed, agreeing with King, Charlie Daniels recalls that Van Zant “had great respect for George Wallace. Ronnie was a southerner, man [and when] they got plaques from the governor ⦠they were just tickled to death about it.”

Yet here too Ronnie had to backtrack, calling the interlude a “bullshit gimmick thing,” neglecting to say that the band kept that hardware and their “commissions” in the militia. And decades later, when the song

was made into the state motto, no one in the band calling itself Lynyrd Skynyrd threw

that

fish back either. Al Kooper tells of the time when, during the recording of

pronounced

, he brought to the studio a guitar that had been given to him by Jimi Hendrix. Someone he identifies only as “one of the Skynyrd boys” began fooling with it, saying, “Hey, Al, this guitar plays nice.” From across the room, Ronnie said, “That guitar used to belong to Jim Hendrix,” whereupon the guy, Kooper says, “let it fall out of his hands onto the couch. â

OOOO⦠I just got some nigger on me!'

he screamed irreverently.”

“You better pick that guitar up,” Ronnie said, “and see if you can get some

more

of that nigger on ya.”

Naturally, such palaver was meant in jest, but it did show how easy it was for men of the South to fall into racially offensive dialogue odious to northerners and progressive southerners. One Yankee journalist, Jaan Uhelszki, who was sent to write a piece about Skynyrd for

Creem

, claimed the experience made her feel like she needed to be deloused. After meeting Rossington, she said she expected him to tell her “some juicy tales of nigger skinnings.” Mark Kemp, then a southern music journalist and later an editor at

Rolling Stone

and vice president at MTV, wrote in his 2004 book

Dixie Lullaby

of visiting Ed King and asking if anyone in the band had ever uttered racist thoughts. “When King's wife, who was sitting at the table with us, chimed in, saying, âOh, please, I remember Gary making a comment just a few years ago,' King immediately interrupted her.” Choosing his words carefully, King then told Kemp, “I don't have any personal experience with that. But I can tell you this: unlike the Allman Brothers, we never had any black people hanging around Lynyrd Skynyrd at all. At all. I mean, none at all.”

Yet, as if King himself had been bitten by the routine, quotidian expression of racism during his time with the band, he too betrayed some rather acrid opinions during the highly charged debate surrounding the Trayvon Martin killing in 2013. King wrote on his Facebook page that young black men were “lazy,” “thugs,” “killers,” and “thieves,” and that blacks in America have “had their reparations.” Kemp, who had believed King was the “enlightened” one in Skynyrd, took that label back.

“I thought he had more insight than other right-wing rockers. I was wrongâ¦. Who the hell does this ex-southern rocker think he is to

moralize so generically and condescendingly about âblacks' he doesn't even know?” (King later scrubbed the offensive remarks from his page.)

As much as Ronnie craved black recognition for Skynyrd, a few bluesy numbers did little to ameliorate centuries of cultural and racial conditioning.

While MCA had gotten down with the flag and was feasting on “redneck chic,” fashioning the band's name in promotional materials and record jackets out of pieces of the Confederate flag, Ronnie began to feel the heat over it. Asked to explain what the flag meant to the act, he did his damndest to deflect the issue by folding it into his general beef about the “establishment”âthe “gimmick”-hungry record company. “It was useful at first,” he allowed, “but by now it's embarrassing.” Years later,

Rolling Stone's

John Swenson bought into this construct that by flying the flag Skynyrd was actually making their own antiestablishment stand, the Old Confederacy being among that establishment. The flag, he wrote, had “some kind of complex relationship to the Confederacy, but it's not about states' rights or slavery; it's something very personal. It's closer to the whole idea of the Declaration of Independence. This was their version of it, being a rebel.”

It was a tortuous rationale, assuming a whole lot, but it did make some sense given the Skynyrd inferiority complex that would never end; as high as they got, they always saw themselves as muttsâdirty dogsânever accepted as anything more by the cultured rock Brahmins and thus never under any obligation to act like anything else. It was a self-serving prophesy and shield, giving them license to act like dogs. If the problem areas of the flag and “Sweet Home Alabama” were thorny, Skynyrd might deflect criticism but embrace the notoriety. In fact, rather than merely let the flag be an avatar, they went even further. Soon their sound equipment was painted battleship gray, a “Confederate” hue that blended in with the backdrop of the flag. Ronnie even strode onto the stage one night clad in a Confederate officer's coat and hatâthough he later laughed it off as a “showbiz stunt,” his way of sending up the whole kerfuffle about the flag.

With so much at stake, all they could do was follow along with it and hope that lame clarifications about the “gimmicks” would keep the

fallout off their backs. However, as time went on they almost became

prisoner

to that flag, even consumed at times by it. The first time Skynyrd took their show across the pond to Europeâa two-month trek beginning in mid-November 1974 with dates in Glasgow and Edinburgh, two weeks in England, three days in Germany, one day each in Belgium and France, and the finale at the Rainbow Theatre in London on December 12âthe flag came too, though Europeans had not the slightest notion of the mortal insult it was to African Americans. As Ronnie reported, patrons such as those the band played for at venues like Britain's Saint George's Hall, Theatre Royal, the Kursaal, Theater An Der Brienne Strasse, Jahrhunderthalle, and Ancienne Belgique “really like all that [Confederate] stuff because they think it's macho American”âwhich of course it was in a good part of America as well.

On one night during the well-attended and well-received tour, Ronnie happened to drop the flag onto the floor; he freaked out, as if he had committed a great sin against the motherland. Reaching for the phone, he called Charlie Daniels back home. The rotund fiddler, who himself had taken to wearing jumpsuits at his concerts covered with the Stars and Bars, recalled that the band had gone as far as to take the flag out to an alley and burn it, in accordance with antebellum protocol for flag desecration.

“Do you think it would be all right if we went on without the flag?” Ronnie asked him. “Certainly,” Daniels replied.

Ronnie sighed in relief. The symbol he insisted was a gimmick and an embarrassment had not been sullied on foreign soil after all. The honor of the South lived on.

The one-story wood-frame house that Lacy Van Zant built for his brood at 1285 Mull Street in “Shantytown,” the hardscrabble neighborhood on the west side of Jacksonville, stands pretty much as it did when Ronnie Van Zant was young.

CAMERON SPIRITAS

Here, at Robert E. Lee High School, which still stands stately on South McDuff Avenue, the Shantytown boys ran afoul of crusty gym coach Leonard Skinner for wearing their hair too long, which earned them suspensions and inspired a ready-made name for their band.

CAMERON SPIRITAS

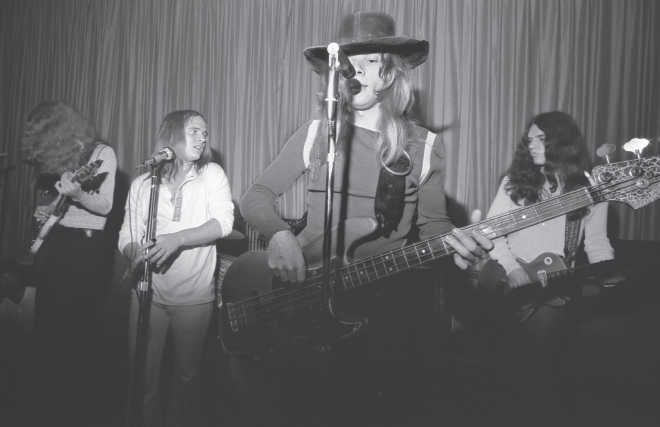

In perhaps the first-known photo of Lynyrd Skynyrd, the bandmates play onstage at Atlanta's dingy Funochio's club on July 21, 1972, with bass man Leon Wilkeson singing lead, while Ronnie Van Zant looks on. Gary Rossington strikes a chord while Allen Collins, his face hidden by hair, focuses on his own guitar.

CARTER TOMASSI

Few would know that a slice of rock history was made in this drab warehouse at 2517 Edison Avenue, which in the early 1970s housed the Little Brown Jug, where Ronnie was inspired to write “Gimme Three Steps,” the semitrue tale of a flirtation gone very wrong.

CAMERON SPIRITAS