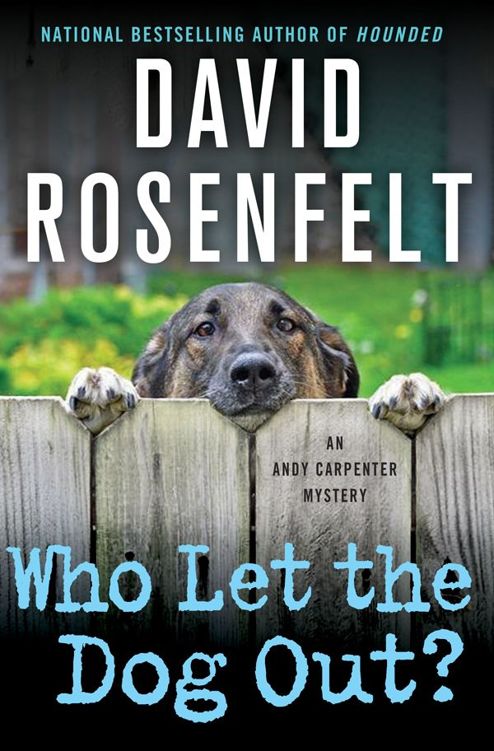

Who Let the Dog Out?

Read Who Let the Dog Out? Online

Authors: David Rosenfelt

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #United States, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Thrillers & Suspense, #Suspense

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click

here

.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

For Riley and Oliver

This was not going to take a master thief. The difficulty of robberies, Gerry Downey knew, was directly proportional to the fear and expectation that the targets had of being robbed. No one goes to extremes to protect property unless they think someone might want to take that property. That’s why banks and jewelry stores are tougher targets than hot dog stands and city dumps.

It’s Robbery 101.

That was why Downey, who over time had accumulated enough real-world robbery credits to earn his master’s, had no concerns about his current job. But that did not mean he was careless about it. He was a pro, and knew it was the easy ones that could occasionally throw you a curve. Which is why he had staked this one out for three days. After all, he was a professional and would act like one, despite the demeaning nature of this particular job.

Of course, the job wasn’t just demeaning; it was also strange. Downey had never stolen anything like this before, and likely never would again. But if the payoff was always going to be this good, he’d happily sign on for a repeat performance anytime.

The building was on Route 20 in Paterson, New Jersey, a heavily trafficked road that had a number of commercial businesses on it. Part of that time he had been watching from a hamburger place across the road, which turned out to be bearable because the burgers were charcoal broiled and damn good and the French fries were crisp.

The guy who ran the place he was watching, Willie Miller, left with his wife most days at around five o’clock in the evening, sometimes a little later. The exact timing seemed to depend on whether they were there alone, or whether a customer was on site. But so far neither Willie nor anyone else had come back once they left, and Downey had watched until eight o’clock each night.

Downey had gone inside the target building the previous morning, pretending to be a customer himself. He needed to learn whether there was a burglar alarm (there was) and whether there were indoor cameras (there were). Neither would cause him any concern.

On this day Miller and his wife didn’t leave until five-fifteen, so Downey waited twenty minutes and then drove over. There was no reason not to do it in daylight. If for any reason anyone was watching, a car pulling up to that building would seem more natural then than at night. And besides, he would only be there a few minutes.

Downey picked the lock in less than ten seconds, and went inside. He knew the silent alarm would be going off, but he’d be out long before anyone could respond. He pulled his jacket up over his head and headed for the electrical box to turn off the cameras. This was accomplished in a few seconds as well.

The only thing that was annoying Downey at that moment, other than the indignity of having to do such an easy job, was the noise. The barking was deafening; he had no idea how Miller could stand it every day.

Downey went directly to the dog runs, stopping at the fourth one on the right. Inside was a large dog, matching the photo he had been given. He didn’t know what kind it was, and didn’t care. Dogs didn’t interest him one way or the other, and it amazed him how some people talked about them like they were human.

He opened the cage, pulling the leash out of his pocket. The dog seemed friendly enough and not inclined to attack, which was a plus, since if Downey had to shoot her, it would have defeated the purpose of his being there.

But her tail was wagging, and she came over and lowered her head, as if she wanted Downey to pet her. That sure as hell wasn’t going to happen, so Downey just put the leash on her and led her out.

Downey took her to his car and she hopped right in. The entire thing hadn’t taken more than three minutes, a very profitable three minutes at that.

“The man is pure evil. He must be stopped.”

“That might be overstating it a bit,” Laurie Collins says. “He’s a baseball coach, working with nine-year-olds.”

I point toward the field. “Do you see where Ricky is? Do you?” I’m talking about our recently adopted son, currently positioned in the outfield.

“Of course I do. He’s in right field.”

I nod vigorously. “Exactly! Right field! That’s where they put the losers, the guys they’re trying to hide. Nobody good plays right field.”

“Ruth, Aaron, Kaline, Clemente, Frank Robinson, Andre Dawson…” The only team sport that Laurie likes is baseball; she loves the history and tradition, and she’s a student of it. If I don’t interrupt, she’ll name fifty great right fielders.

“Believe me, those guys didn’t play right field in Little League,” I say. “They pitched or played shortstop. In the majors, right field is fine; in Little League it’s Death Valley. This coach has no idea what he’s doing.”

“Don’t talk to him, Andy. Don’t be one of those parents.”

The coach is Bill Silver, and since he’s at least six-two and 210 pounds, there’s no way that I, Andy Carpenter, am going to confront him. I can’t be one of “those parents,” as Laurie put it, because “those parents” usually aren’t cowards.

Laurie and I have been married five months, and we adopted Ricky at the same time. It was too late to get him involved in peewee football, so this is my first chance to see him on an athletic field.

The next batter hits a fly ball to right field. Ricky doesn’t panic, just circles under it, waiting patiently for it to come down. And it does in fact come down, about eight feet to the right of where Ricky is standing. Displaying keen baseball instincts, he runs over and picks it up, then throws it to no one in particular, but in the general area of the infield. And it almost reaches the infield by the time it stops rolling.

“Good try, Rick!” Laurie calls out.

“He’s a shortstop,” I say to no one in particular. “Shortstops don’t catch fly balls. You put Derek Jeter out there, and he embarrasses himself. You ever see Cal Ripken try to catch a fly ball? Pathetic.”

“Andy, Ricky’s having fun.”

“You don’t get to the majors by having fun,” I say.

“Majors?” Laurie says, her voice both incredulous and disapproving. “Is that your plan?”

“Why not? I could have made it to the majors myself, if I had the breaks, and the dedication, and the ability. Why can’t Ricky make it?”

“Well, for one thing, maybe he isn’t good enough.”

“That’s because he’s not focused on baseball. You need to stop bothering him, cluttering his head with that other stuff.”

“What other stuff?”

“You know … like reading and math. When is he going to need that junk in his life? Nobody reads anymore; everything is video.”

“Andy…” I’ve got a hunch that the next words out of Laurie’s mouth are not going to be “I agree with you completely.” But I don’t get to hear them, because my cell phone rings and she stops in midsentence.

Caller ID tells me that it’s Willie Miller, my former client and current partner in the Tara Foundation, our dog rescue operation. Willie and his wife, Sondra, are completely dedicated to finding loving homes for the dogs we bring in.

“What’s up?” is the way I answer the phone.

“We’ve had a robbery,” he says.

“At your house?”

“No, at the foundation. Sondra and I went to get something to eat after work, and when we got home I noticed that the alarm had gone off. So I came down here to see what was going on. There was a break-in.”

I’m a little confused, because there is really nothing to steal there. We don’t keep money or valuables in that building, just dogs. “What did they steal?”

“The shepherd mix. Cheyenne.”

“I’ll be right there,” I say to Willie, and then turn to Laurie, who has overheard my end of the conversation. “Somebody stole a dog from the foundation.”

“That’s bizarre,” she says, which is true. These are dogs up for adoption; there should be no reason for someone to steal one. “You go down there; I’ll get a ride home with Sally.”

Sally Rubenstein is our neighbor, and her son Will is on the same team as Ricky. They are best friends, but unfortunately, Will is playing shortstop, and he fields grounders like Ozzie Smith.

“Okay. If you get a chance after the game, talk to Coach Silver about Ricky.”

“What do you want me to say?” she asks.

“Tell him Ricky should play in the infield or pitch. Don’t overtly threaten him, but make sure he sees your gun.” Laurie is an ex-cop and the private investigator for my law practice, and she carries a handgun.

“Good-bye, Andy.”

“The guy shut the cameras off. And he picked the lock. He knew what he was doing.”

I have to agree with Willie on his assessment, though it seems to make very little sense. Why would an accomplished thief come in and take a stray dog that was already up for adoption?

“You look at the tape?” I ask. “We get anything before he shut it off?” The cameras were not designed to capture thieves in action; we never contemplated that there might be a need. They were actually set up as a webcam, so Willie can see from his home what’s going on with the dogs, in case any are sick. Cheyenne’s run would therefore be within view of one of the cameras.

“Nah. He had his head covered with his sweatshirt; from some kind of college, I think. But we’ve got the GPS, unless the guy removed it.”

They make inexpensive GPS devices that are small and attach to dogs’ collars. We started using them about six months ago, when one of the dogs we adopted out escaped from his new owner. We searched for three days before we found the poor dog. If a dog is going to get away, it is likely to be before he or she is acclimated to the new home, so now we do the GPS thing as a service to protect both the dog and the adopter.

“Let’s take a look.”

We go into the office, and Willie takes the tracking machine out of the cabinet. He turns it on, and we wait the few seconds until it’s ready. Once it is, Willie punches in the number that identifies Cheyenne’s collar.

“We got it,” he says. “Twenty-sixth Street, off Nineteenth Ave. Let’s go.”

“We should call the police,” I say. “Have them meet us there.”

“The police? For a stray dog? We can handle this.”

Willie is a black belt in karate and one of the toughest people I’ve ever met. He can also be very nice, as evidenced by the fact that he used the pronoun “we.” He knows very well that if there is any “handling” to be done, I’ll be of little use.