Why do Clocks run clockwise? (22 page)

Read Why do Clocks run clockwise? Online

Authors: David Feldman

These numbers are impressive, but let’s face it: making the same paper bags day in and day out is not the most exciting job in the world. So many manufacturers have decided that, in order to promote pride and a sense of responsibility in the workers, employees would “sign” their work.

166 / DAVID FELDMAN

In most cases, the name you see on the bottom of the bag (usually just a first name) is that of the person who actually made the bag.

Sometimes it is the name of the inspector responsible for supervising the production of the bags by other workers. While inspection certificates in clothing (such as “Inspected by No. 7”) are there to monitor quality control, the names on grocery bags are intended solely to add to the esprit de corps.

At the Stone Container Corporation, many of the workers who run the bag machines have their full names on the bag, preceded by the words, “Produced with Pride by:” If most manufacturers included that inscription, this Imponderable wouldn’t exist, and the mystique of “Toms,” “Dicks,” and “Harriets” on the bottom of shopping bags wouldn’t linger.

Submitted by Kathi Sawyer Young, of Encino, California

.

WHY DO CLOCKS RUN CLOCKWISE? / 167

Why Do Chinese Restaurants Use Monosodium

Glutamate? Other Ethnic Restaurants Don’t Use

It And It Certainly Is Not a Traditional Part of the

Native Cuisine.

Actually, you are just as likely to encounter MSG in a Japanese or Indian restaurant as in a Chinese restaurant. And MSG

has

been a traditional part of Chinese cuisine. Sort of.

Glutamate has been used by Oriental cooks for more than two millennia, but not glutamate out of a shaker. Chefs noticed that soup stock made from

Laminaria japonica

, a certain seaweed, tasted better.

They didn’t know at the time that what was special about this strain of seaweed was that it contained large amounts of natural glutamate.

The discovery of the links between seaweed, monosodium glutamate, and flavor is credited to Professor Kikunae Ikeda of 168 / DAVID FELDMAN

the University of Tokyo, who, in 1908, isolated the specific component of

Laminaria japonica

that enhanced flavor. While Western scientists believed there were only four basic tastes—sweet, sour, salty, and bitter—Ikeda believed in what the Japanese call

umami

, or tastiness, as a separate component. The mystery of

umami

is what the professor was trying to discover by unraveling the composition of the seaweed.

Dr. Ikeda was so enthusiastic about the power of MSG that commercial production of the substance was soon undertaken in Japan. MSG is essentially a concentrated form of sodium. It is extracted from seaweed in the Orient and from seaweed, beets, and grains in the West. Bean curd and soy sauces also tend to contain MSG.

Japan and China are still the largest consumers of MSG, but it is used throughout the world (about 200,000 tons of it annually), and the United States, which didn’t start producing it until the 1940s, eats its share—not only in Chinese and Japanese restaurants, but in many prepared foods.

One of the reasons many people associate MSG with Chinese food is the dreaded “Chinese restaurant syndrome,” whose sufferers insist that they have strong allergic reactions to the chemical. One Chinese restaurant in New York City was so beset by requests from Occidentals to omit the ingredient from its food that all the waitresses donned white aprons with large block letters emblazoned with the immortal words, “No MSG.”

The Glutamate Association (yes, there is a trade organization just for glutamate producers) insists that MSG is perfectly safe. They argue that MSG is no different from the glutamate that is liberated by our bodies when we eat food protein, and that MSG added to food represents only a small fraction of the glutamate contained naturally in most foods. For example, most recipes call for half a teaspoon of MSG per pound of meat. With these proportions, the MSG in a serving of chicken would constitute less than 10 percent of the glutamate already found in the chicken.

While the U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists MSG as

“Generally Recognized as Safe,” a category that includes other WHY DO CLOCKS RUN CLOCKWISE? / 169

common food additives such as salt, pepper, and sugar, many Americans feel that any food that can cause intense allergic reactions must be harmful, and despite its advocacy even the Glutamate Association cites the World Health Organization’s recommendation to limit MSG consumption to a maximum of one-third of an ounce a day (far more than the average American eats). So the question persists: why do restaurateurs and food packagers insist on including an additive that many people don’t want and can’t really distinguish by taste even if included?

MSG’s greatest attribute is its ability to blend flavors well, especially the flavor of mixed spices, which is a reason why Indian cooks, so spice-conscious, tend to use MSG in great quantities. MSG tends to soften the astringent qualities of some foods. Tomatoes taste less acidic with MSG; potatoes less earthy; onions less strong.

For many of the same reasons, a number of chefs disdain MSG, believing that it deadens the taste of foods and is too often used to compensate for inferior products. Others feel there is a thin line between “blending” and “harmonizing” tastes and making all foods taste the same. Some object, in principle, to the idea of using any additive (even a naturally derived one) to enhance the natural taste of a meat, though this same argument could be made against using salt or pepper.

Many consumers confuse MSG with meat tenderizers (which often contain MSG as an ingredient). MSG does not act as either a spice or a tenderizer. Tenderizers act through the use of purified papain, a protein-splitting enzyme extracted from the juice of unripe papayas.

It is confusion between MSG and tenderizers that is often the cause of nervous confrontations in Chinese restaurants. The waiters think that the Americans are being oversensitive to MSG, particularly because, more often than not, MSG will be contained in the base of sauces even if your “no MSG” orders are followed—your request will merely prevent additional MSG from being sprinkled on. The customer is sure that MSG is an ingredient the sole purpose of which is to

170 / DAVID FELDMAN

reduce tough, rubbery meat into something edible, while the cook is likely to dash a few more sprinkles of MSG on his own food if he has the chance.

Submitted by Ronald C. Semone, of Washington, D.C

.

Why Do Old Men Wear Their Pants Higher Than

Young Men?

We couldn’t find too many clothing or gerontological authorities who specialized in this subject, but just about everyone we contacted was more than happy to offer speculations. So, until the

Encyclopae-dia Britannica

prints an entry on “Pants Height,” we’ll just have to write the definitive treatment ourselves.

The most common explanation we received from clothiers is that as men get older, they lose a little height and the spine curves a bit.

Thus, a pair of pants that might have hung at waist level a few years ago will now creep upward. The one problem with this theory: when old men go to buy new pants, they still buy pants that hang high.

WHY DO CLOCKS RUN CLOCKWISE? / 171

The second most popular explanation of this nagging social problem is the “Paunch Theory,” which postulates that high-riding pants are a pathetic attempt to hide abdominal excesses. While this idea makes eminent sense, it doesn’t explain why younger men with truly awesome beer bellies wear their pants low and let their stomachs hang unfettered.

But one wise man, Fred Shippee, of the American Apparel Manufacturers Association, offered the most logical explanation. Pants were cut relatively high until the jeans craze of the 1960s. Most men above the age of fifty, let alone much older men, never had the experience of wearing pants designed to hang on the hips rather than on the waist, and they feel uncomfortable starting now. To someone used to wearing high-cut pants, hip huggers feel as if they are always on the verge of falling off.

The low cut of jeans (called “low-rise”) truly revolutionized menswear and literally lowered our sights. When we see “high-rise”

pants, we think “old” or “nerd.” While much has been written about the ups and downs of women’s hemlines, we hope that this chapter will stir compassion for men who wear their pants high or low, and eventually bring about world peace.

172 / DAVID FELDMAN

Why Are Oreos Called “Oreos”?

Although the world’s most popular cookie recently celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary, the origin of its name is shrouded in mystery. It was first marketed in Hoboken, New Jersey, on March 6, 1912 as the Oreo Biscuit. In 1921, the name was changed to the Oreo Sandwich. In 1948, the same cookie was renamed the Oreo Creme Sandwich. Ultimately, in 1974, the immortal Oreo Chocolate Sandwich Cookie was born, a name that should last forever or until it is changed again, whichever comes first.

Of course, the lack of definitive facts has not deterred Oreo scholars from speculating on why those four magic letters were thrown together. Michael Falkowitz, a representative of Nabisco WHY DO CLOCKS RUN CLOCKWISE? / 173

Brands Customer Relations, offers two of the more popular theories: 1. Mr. Adolphus Green, first chairman of the National Biscuit Company (founded in 1898 from the consolidation of the American Biscuit Co., the New York Biscuit Co., and the United States Baking Co.) was fond of the classics. The name “Oreo” is Greek for

“mountain.” It was said in early testing that the cookie resembled a mountain.

2. The name was derived from

or

, the French word for “gold.”

The original Oreo label had scrollwork in gold on a pale green background, and the product name was also printed in gold.

After the first printing of this book, we received several letters from Greek readers indicating that the Greek word for “mountain”

is not

oreo

but

oros

. Furthermore, a Greek word that, phonetically, sounds like

oreo

, means “nice,” “attractive,” and even “delicious.”

Could this, and not Nabisco’s “mountain theory,” be the real answer to the origins of our number one cookie?

Submitted by Ronald C. Semone, of Washington, D.C

.

174 / DAVID FELDMAN

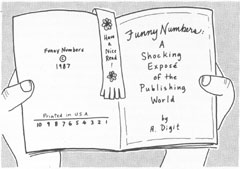

What Are Those Funny Numbers on the Bottom of

Copyright Pages in Books?

Look at the bottom of the copyright page of this book. Unless someone at the typesetter’s has played an elaborate practical joke on us, you should see a row of numbers with a few letters—something like this:

87 88 89 90 ??? 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

These funny numbers are simply a code designed to signify which printing of the book you have purchased. The number farthest to the right is the printing your have bought (in the example above, you would have bought the first printing). Harper & Row and some other publishers also mark the year of the printing, indicated by the number at the far left (in the example above, 1987). This practice is reassuring to paranoid writers, who

WHY DO CLOCKS RUN CLOCKWISE? / 175