Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? (13 page)

Read Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? Online

Authors: David Feldman

O

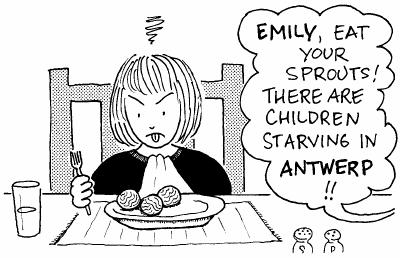

h ye of little faith! You might not be able to find Russian dressing in Moscow or French dressing in Paris, but Belgium is happy to stake its claim on its vegetable discoveries—endive and Brussels sprouts and, for that matter, “French” fries.

Although there have been scattered reports about Brussels sprouts first being grown in Italy during Roman times, the first confirmed sighting of cultivation is near Brussels in the late sixteenth century. We don’t know whether the rumor is true that there was a sudden upsurge of little Belgian children running away from home during that era.

We do know that by the end of the nineteenth century, Brussels sprouts had been introduced across the European continent, and had made the trek across the Atlantic to the United States. Today, most Brussels sprouts served in North America come from California.

Both the French (

choux de Bruxelles

) and the Italians (

cavollini di Bruselle

) give credit to Brussels for the vegetable, and Belgians are so modest about their contributions to the deliciousness of chocolate, mussels, and beer, who are we to argue?

Submitted by Bill Thayer of Owings Mills, Maryland. Thanks also to Mary Knatterud of St. Paul, Minnesota.

R

eader Tim Goral writes:

We live in 2004

A.D.

[well, we did a few years ago], or

anno domini

(the year of our Lord); the time period of human history that supposedly began with the birth of Jesus Christ. The historical references before that are all “

B.C

.” (or sometimes “

B.C.E.

”), so my question is: How did the people that lived, say 2500 years ago, mark the years? I understand that we count backward, as it were, from 2

B.C

. to 150

B.C

. to 400

B.C

., etc., but the people that lived in that time couldn’t have used that same method. They couldn’t have known they were doing a countdown to one. What did they do? For example, how did Aristotle keep track of years?

In his essay, “Countdown to the Beginning of Time-Keeping,” Colgate University professor Robert Garland summarized this question succinctly: “Every ancient society had its own idiosyncratic system for reckoning the years.” We’ll put it equally succinctly and less compassionately: “What a mess!”

Since we couldn’t contact ancient time-keepers (a good past-life channeler is hard to find), this is a rare Imponderable for which we were forced to rely on books. We can’t possibly cover all the schemes to mark time that were used, so if you desire in-depth discussions of the issue, we’ll mention some of our favorite sources at the end of this chapter.

Our calendar is a gift from the Romans, but because early reckonings were based on incorrect assessments of the lunar cycles, our system has changed many times. “

A.D.

” is short for

Anno Domini Nostri Iesu Christi

(“in the year of our lord Jesus Christ”); the years before that are designated “

B.C.

” (before Christ). Obviously, the notion of fixing a calendar around Jesus did not occur immediately on his birth. Religious scholars wrestled with how to fix the calendar for many centuries.

In the early third century

A.D.

, Palestinian Christian historian Sextus Julius Africanus attempted to fix the date of creation (he put it at what we would call 4499

B.C.

, but he had not yet thought of the

B.C./A.D.

calendar designation). In the sixth century, Pope John I asked a Russian monk, Dionysius Exiguus, to fix the dates of Easter, which had been celebrated on varying dates. Exiguus, working from erroneous assumptions and performing errors in calculation, was the person who not only set up our

B.C./A.D.

system, but helped cement December 25 as Christmas Day (for a brief examination of all of the monk’s mistakes see http://www.westarinstitute.org/Periodicals/ 4R_Articles/Dionysius/dionysius.html). Two centuries later, Bede, an English monk later known as Saint Bede the Venerable, popularized Exiguus’s notions. Christians were attempting to codify the dates of the major religious holidays, partly to compete with Roman and Greek gods and the Jewish holidays, but also to make the case for a historical Jesus.

Although the world’s dating schemes are all over the map (pun intended), most can be attributed to one of three strategies:

1. Historical Dating.

Christian calendars were derived from the calendars created by the Roman Empire. The early Romans counted the years from the supposed founding of Rome (

ab urbe condita

), which they calculated as what we would call 753

B.C.

The ancient Greeks attempted to establish a common dating system in the third century

B.C.

, by assigning dates based on the sequence of the Olympiads, which some Greek historians dated back as far as 776

B.C.

2. Regnal Dating.

If you were the monarch, you had artistic control over the calendar in most parts of the world. In the ancient Babylonian, Roman, and Egyptian empires, for example, the first year of a king’s rule was called year one. When a new emperor took the throne—bang!—up popped a new year one. Although Chinese historians kept impeccable records of the reign of emperors, dating back to what we would call the eighth century

B.C.

, they similarly reset to year one at the beginning of each new reign. In ancient times, the Japanese sometimes used the same regnal scheme, but other times dated back to the reign of the first emperor, Jimmu, in 660

B.C.

3. Religious Dating.

Not surprisingly, Christians were not the only religious group to base their numbering systems on pivotal religious events. Muslims used hegira, when Mohammed fled from Mecca to Medina in 622

A.D.

to escape religious persecution, to mark the starting point of their calendar. In Cambodia and Thailand, years were numbered from the date of Buddha’s death. Hindus start their calendar from the birth of Brahma.

Looking over the various numbering schemes, you can’t help but notice how parochial most calendar making was in the ancient world. Even scholars who were trying to determine dates based on astronomical events often ended up having to bow to political or religious pressure. And modern society is not immune to these outside forces—some traditionalist Japanese activists are trying to reintroduce a dating system based on the emperors’ reigns.

Submitted by Tim Goral of Danbury, Connecticut.

For more information about this subject, one of the best online sources can be found at http://webexhibits.org/calendars/index.html. Some of the books we consulted include

Anno Domini

:

The Origins of the Christian Era

by George Declercq;

Countdown to the Beginning of Time-Keeping

by Robert Garland, and maybe best of all, the

Encyclopaedia Britannica

section on “calendar.”

W

hen we posed this Imponderable to reader Ken Giesbers, a Boeing employee, he wrote:

I understand this one on a personal level. On one of the few occasions that I flew as a child, I had the good fortune of getting a window seat, but the misfortune of sitting in one that lined up with solid fuselage between two windows. Other passengers could look directly out their own window, but not me. I would crane my neck to see ahead or behind, but the view was less than satisfying. Why would designers arrange the windows in this way?

From the airplane maker’s point of view, the goal is clearly, as a Boeing representative wrote

Imponderables,

to

provide as many windows as they reasonably can, without compromising the integrity of a cabin that must safely withstand thousands of cycles of pressurization and depressurization.

But the agenda of the airlines is a little different. Give passengers higher “seat pitch” (the distance between rows of seats) and you have more contented passengers. Reduce the seat pitch and you increase revenue if you can sell more seats on that flight. In 2000, American Airlines actually reduced the number of rows in its aircraft, increasing legroom and boasting of “More Room Throughout Coach” in its ads. When the airline started losing money, it panicked and cut out the legroom by putting in more rows.

In 2006, when soaring fuel prices are squeezing the airlines’ costs, there isn’t much incentive to offer more legroom. Their loads (percentage of available seats sold) are high; if they reduce the number of seats available on a flight, there is a good chance they have lost potential revenue on that flight. And passengers who are concerned with legroom might spring for more lucrative seats in business or first class. On the other hand, the more you squish your passengers, the more likely you are to lose your customer to another airline who offers higher seat pitch (the downsizing of American Airline’s legroom in coach lost them one

Imponderable

author to roomier Jet-Blue). Web sites such as SeatGuru.com pinpoint the exact pitch dimensions of each aircraft on many of the biggest airlines, heating up the “pitch war.”

A few inches of legroom can have huge consequences. Tens of millions of dollars can be involved in such decisions. Cabin seats can be moved forward or backward on rails fairly easily, but the costs are not just for equipment and the labor involved in reconfiguring the planes, but in downtime while they are reconfigured.

As you might guess, the sight lines of window passengers aren’t uppermost in the minds of the airlines. If you happen to have a clear shot at the window from your seat, consider it serendipity.

Submitted by Alex Ros of New York, New York. Thanks also to John Lai of Billerica, Massachusetts; and Kevin Bourillon, of parts unknown.

N

ow that cassette decks in automobiles have been largely replaced by CD players and satellite radios, it’s easy to forget that the auto-reverse function on cassette players was introduced in cars to allow drivers to keep their hands on the steering wheel instead of the stereo. The auto-reverse feature is reliable because it is so simple. It turns out that the reverse kicks in when a sensor “knows” that the sprockets (the two protrusions in which you click in the holes of the cassette) have stopped turning.

Robert Fontana, formerly of TDK Electronics Corporation, wrote to

Imponderables:

Auto-reverse cassette decks employ a special playback head and mechanical gears that are governed and switched electronically. When a cassette tape reaches the end of side A, a sensor detects that the cassette hub is no longer revolving. Consequently, a signal is sent to reverse the polarity of both the capstan shaft and reel drive motors so that the cassette tape will travel in a right to left path. Additionally, the head gaps of the playback head are also switched to properly reproduce the left and right channels of side B. At the conclusion of side B, every parameter is then switched again to playback side A.

Submitted by Ernie Capobianco of Dallas, Texas.