Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? (21 page)

Read Why Do Pirates Love Parrots? Online

Authors: David Feldman

REVVING IS—I HAVE NO IDEA!

Next to those who professed to love the Sound, the most popular answer was: “I don’t know,” but the love of blipping is the expression of an inchoate joy:

We do it because we can, honestly. I sometimes do it in my toy car for the sake of it, but on the motorcycle, it’s one of those, “Hey, I’m here” things. It’s our way to express ourselves while stationary.

I do it. I’m a blipper. I do it for lots of reasons. To be cool, to let others know I’m there and for well, I don’t know. I just do it. I guess that makes me an addict…. the first step in recovery is to admit…I’m a blipping blipper…

THE CASE AGAINST BLIPPING

This Imponderable exposed divisions within all three online communities of bikers. Cyclists are acutely aware of their image among nonriders, and some commented on this schism:

As you may gather from some of the…posts, many riders are quite defensive about this—there is an attitude that they have the right to make noise, and damn any objections. In the motorcycle world, aftermarket mufflers and exhaust systems are commonplace—a lot of guys will install them strictly for loudness, with no concern about performance gains…. And of course, once you’ve spent hundreds or thousands of dollars on a loud exhaust system, you want to hear it—so you’ll sit and rev it at red lights, getting envious looks from any guy within sight and dreamy eyes from the women, as you sneer from beneath your do-rag—but oops, I digress. As I said, some of us ride motorcycles because they’re fun to ride, and don’t feel that annoying the non-riding public with excess noise is required, or politic.

Most of our motorcycle enthusiasts were in the pro-blip camp or the anti-blip minority. Few were sympathetic to both sides. We exchanged a fascinating series of e-mails with “Hawkster,” who is attracted to the scream and the danger of motorcycles and other macho symbols, but is also aware of their pitfalls:

As a former range safety officer and instructor at an outdoor shooting range and as a current riding instructor, I’ve noticed a lot of similarities in the mind-sets of both shooters and motorcyclists. I know that if it’s both noisy and dangerous, it will probably draw my interest!

Many people own either guns or motorcycles because they feel empowered by them. Whether or not this is a good thing is a matter of some debate among instructors. I believe that it ultimately comes back to how a particular object or pursuit makes us feel—I’ve seen the “I’m a bad-ass” look on many a new shooter’s face. Unfortunately, empowerment only comes through proficiency, but most don’t seem to realize that.

Many riders, particularly the newer ones, are under the illusion that they are able to buy into the movie-and television-created “biker mystique” with the purchase of a machine. I call this the “bad-ass by proxy” syndrome…Crash statistics indicate that it doesn’t usually bode well for their riding career.

Much of my time at the shooting range was spent stomping out myths about guns. Oddly, I seem to spend just as much time doing the same during motorcycle classes.

We were impressed with how thoughtful Hawkster was, so we asked him why he’s so attracted to the noise and danger himself. He replied:

As an instructor, I can get all the attention without it becoming socially unacceptable (Are revving bikers straddling that line?). The need for attention is probably a “shadow motive” for many actors, activists, and teachers.

Regarding shooting and riding motorcycles on the street and in competition: I think that some people just function best in a threat-rich environment. I’m that type of person. Many of us have been labeled as ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder). I think it really gets your attention when your life is on the line. We enjoy that. I consider riding to be transpotainment.

I don’t think that anyone ever really grows up. We’re just forced into acting like it by cultural mores. Riding a motorcycle permits us to be (borderline) socially acceptable kids.

The Sound is both the boon and the bane to Harley devotees. A few years ago, when Harley-Davidson celebrated its one-hundredth anniversary, upstart motorcycle manufacturer BMW posted this billboard on the Interstate: “We’d say congratulations on your 100

th

. But you wouldn’t hear us.”

Submitted by Douglas Watkins, Jr. of Hayward, California. Special thanks to all the participants of the Motorcycle USA, GSResources.com, and HarleyZone message boards.

S

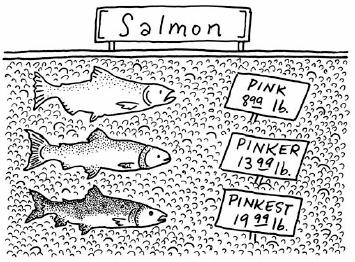

almon are pink for the same reason that lobsters, crabs, crawfish, shrimp, and for that matter, flamingos are pink: They are what they eat. Salmon feast on shrimp, krill, and other small fish that are full of asataxanthin, a carotenoid (much like the beta carotene that give carrots their orange hue) that not only adds the reddish pigment to the salmon’s flesh, but provides plenty of vitamin A.

Skeptical

Imponderables

readers might think this answer is fishy for one big reason. Most salmon we see in supermarkets, fish stores, and restaurants are not wild salmon, but farm-raised. These farm-raised salmon are not pampered with shrimp cocktail feasts—they are given a less expensive commercial feed.

That feed is infused with plenty of asataxanthin for the most compelling of reasons: the color of salmon is a major factor in its consumer appeal. In a paper, “Salmon Color and the Consumer,” Stewart Anderson of Hoffman-La Roche Limited wrote:

Consumers perceive that redder salmon is equated to these characteristics: fresher, better flavor, higher quality, and higher price.

Anderson makes clear that redder salmon doesn’t taste any better and is not any fresher, but the bottom line is clear, which is why you are unlikely to see any pale salmon, from whatever source, in your store or on your plate.

Submitted by Simon Parker-Shames of Ashland, Oregon.

W

ouldn’t it be cool to be lost in the jungles of Belize and have a yellow-headed parrot assist us with a timely: “Hey buddy, bear left!”?

Cool? Yes. Likely? No way. As far as we know, birds, even chatty ones like parrots and mynahs, do not mimic human speech in the wild, but they do imitate other sounds, and especially other birds.

In the wild, birds mimic for a variety of reasons. Depending upon the circumstances, birds feigning the songs of other species can attract members of the opposite sex, fool predators into misidentifying the species of the singer, or ward off competitors for food or territory. Since humans are usually capable of differentiating between the song of a mimic from the song of the bird the mimic is imitating, it’s likely that the impersonation isn’t fooling other birds (whose hearing is much more sensitive than ours) either. But like humans, birds would rather avoid confrontation or competition than face it head on—mimicking clearly works.

Birds are flock creatures. Closeness within its species is crucial to a parrot’s survival in the world: While one parrot focuses on foraging, others look for predators. When taken out of the wild and into a household, birds will imprint with their human owners. Mimicking seems to be a way to foster closeness with their human “flock-mates.” As Todd Lee Etzel, an officer of The Society of Parrot Breeders and Exhibitors, wrote

Imponderables:

The pet bird becomes imprinted with human vocalizations and hence mimicking takes place due to the bird’s desire to be part of the “flock,” even though it is not a natural one. Keep in mind that most species of parrots are highly social and the need for social interaction is so strong that innate behavior is modified to fit the situation.

If pet birds are motivated by social interaction, why do they tend to mimic at least as much when their owners leave the room? Animal behaviorist W. H. Thorpe offers a theory:

as they develop a social attachment to their human keepers, they learn that vocalizations on their part tend to retain and increase the attention they get, and as a result vocal production, and particularly vocal imitation, is quickly rewarded by social contact. This seems an obvious explanation of the fact that a parrot when learning will tend to talk more when its owner is out of the room or just after he has gone out—as if he is attempting, by his talking, to bring him back.

Thorpe’s theory advances the notion that bird psychology differs little from infant psychology, which isn’t farfetched in the least. Dr. Irene Pepperberg, a research scientist at MIT and a professor at Brandeis University, has studied and written about the abilities of African Gray parrots, particularly her oldest bird, Alex. Just as other scientists have proven that primates are capable of complex communication, so Pepperberg has shown that parrots can do far more than mimic. If shown two blocks that are identical except for their hue, and is asked what is different about them, Alex will answer “Color.” He has mastered numbers, and shapes, and locations, and the names of objects, and has learned to ask, or more accurately, demand them: “If he says that he wants a grape and you give him a banana, you are going to end up wearing the banana.” Pepperberg estimates that Alex’s cognitive ability is comparable to a four-to six-year-old child, with the emotional maturity of a two-year-old.

Pepperberg plays a version of the classic shell game with Alex and other parrots, hiding nuts below one of three cups. Alex usually succeeds at spotting the nut, except when the experimenter doesn’t play fair. Sometimes, the scientists will deceive the parrot by sneaking the nut under another cup while distracting him from the subterfuge:

So Alex goes over to where he expects the item to be, picks up the cup, and finds that the nut is not there; he starts banging his beak on the table and throwing the cups around. Such behavior shows that Alex knew that the object was supposed to be there, that it’s not, and he’s giving very clear evidence that he perceived something, and that his awareness and his expectations were violated.

In the wild, parrots use their wits to evade predators and find food and mates. The need to solve problems might be as innate in a parrot as its mimicking skills. If a parrot’s cognitive skills are as great as Alex has exhibited, Pepperberg implores pet owners to provide the proper stimulation:

I try to convince them that you can’t just lock it in a cage for eight hours a day without any kind of interaction. I don’t mean just interpersonal interaction, or having other birds around; parrots have to be intellectually challenged.

Etzel thinks that parrots and other birds mimic our language and other sounds in their environment “simply because they are able to do so. It might even be a form of entertainment for them.” Indeed, parrots might be musing about us while we are “training them”:

Doesn’t my owner look silly constantly repeating “Polly wanna cracker?” Oh well, might as well go through the drill if it’s going to end up with some tasty carbs down my gullet.

Submitted by Wayne Lipe of Long Beach, New York.