Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (20 page)

Authors: Michael Shermer

Tags: #Creative Ability, #Parapsychology, #Psychology, #Epistemology, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #Philosophy, #Creative ability in science, #Skepticism, #Truthfulness and falsehood, #Pseudoscience, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Belief and doubt, #General, #Parapsychology and science

Finally, the sexual component of alien abduction experiences demands comment. It is well known among anthropologists and biologists that humans are the most sexual of all primates, if not all mammals. Unlike most animals, when it comes to sex, humans are not constrained by biological rhythms and the cycle of the seasons. We like sex almost anytime or anywhere. We are stimulated by visual sexual cues, and sex is a significant component in advertising, films, television programs, and our culture in general. You might say we are obsessed with sex. Thus, the fact that alien abduction experiences often include a sexual encounter tells us more about humans than it does about aliens. As we shall see in the next chapter, women in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were often accused of (and even allegedly experienced or confessed to) having illicit sexual encounters with aliens—in this case the alien was usually Satan himself— and these women were burned as witches. In the nineteenth century, many people reported sexual encounters with ghosts and spirits at about the time that the spiritualism movement took off in England and America. And in the twentieth century, we have phenomena such as "Satanic ritual abuse," in which children and young adults are allegedly being sexually abused in cult rituals; "recovered memory syndrome," in which adult women and men are "recovering" memories of sexual abuse that allegedly occurred decades previously; and "facilitated communication," where autistic children are "communicating" through facilitators (teachers or parents) who hold the child's hand above a typewriter or computer keyboard reporting that they were sexually abused.

We can again apply Hume's maxim: is it more likely that demons, spirits, ghosts, and aliens have been and continue to sexually abuse humans or that humans are experiencing fantasies and interpreting them in the social context of their age and culture? I think it can reasonably be argued that such experiences are a very earthly phenomenon with a perfectly natural (albeit unusual) explanation. To me, the fact that humans have such experiences is at least as fascinating and mysterious as the possibility of the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence.

7

Epidemics of Accusations

Medieval and Modern Witch Crazes

I

n the small town of Mattoon, Illinois, a woman says that a stranger entered her bedroom late at night on Thursday, August 31, 1944, and anesthetized her legs with a spray gas. She reported the incident the next day, claiming she was temporarily paralyzed. The Saturday edition of the Mattoon

Daily Journal-Gazette

ran the headline "ANESTHETIC PROWLER ON LOOSE." In the days to come, several other cases were reported. The newspaper covered these new incidents under the headline "MAD ANESTHETIST STRIKES AGAIN." The perpetrator became known as the "Phantom Gasser of Mattoon." Soon cases were occurring all over Mattoon, the state police were brought in, husbands stood guard with loaded guns, and many firsthand sightings were recounted. In the course of thirteen days, a total of twenty-five cases were reported. After a fortnight, however, no one was caught, no chemical clues were discovered, the police spoke of "wild imaginations," and the newspapers began to characterize the story as a case of "mass hysteria" (see Johnson 1945; W. Smith 1994).

Where have we heard all this before? If this story sounds familiar, it might be because it has the same components as an alien abduction experience, only the paralysis is the work of a mad anesthetist rather than aliens. Strange things going bump in the night, interpreted in the context of the time and culture of the victims, whipped into a phenomenon through rumor and gossip—we are talking about modern versions of medieval witch crazes. Most people do not believe in witches anymore, and today no one is burned at the stake, yet the components of the early witch crazes are still alive in their many modern pseudoscientific descendants:

1. Victims tend to be women, the poor, the retarded, and others on the margins of society.

2. Sex or sexual abuse is typically involved.

3. Mere accusation of potential perpetrators makes them guilty.

4. Denial of guilt is regarded as further proof of guilt.

5. Once a claim of victimization becomes well known in a community, other similar claims suddenly appear.

6. The movement hits a critical peak of accusation, when virtually everyone is a potential suspect and almost no one is above suspicion.

7. Then the pendulum swings the other way. As the innocent begin to fight back against their accusers through legal and other means, the accusers sometimes become the accused and skeptics begin to demonstrate the falsity of the accusations.

8. Finally, the movement fades, the public loses interest, and proponents, while never completely disappearing, are shifted to the margins of belief.

So it went for the medieval witch crazes. So it will likely go for modern witch crazes such as the "Satanic panic" of the 1980s and the "recovered memory movement" of the 1990s. Is it really possible that thousands of Satanic cults have secretly infiltrated our society and that their members are torturing, mutilating, and sexually abusing tens of thousands of children and animals? No. Is it really possible that millions of adult women were sexually abused as children but have repressed all memory of the abuse? No. Like the alien abduction phenomenon, these are products of the mind, not reality. They are social follies and mental fantasies, driven by a curious phenomenon called

the feedback loop.

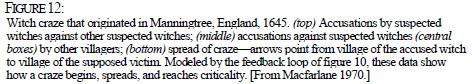

A Witch Craze Feedback Loop

Why should there be such movements in the first place, and what makes these seemingly dissimilar movements play out in a similar manner? A helpful model comes from the emerging sciences of chaos and complexity theory. Many systems, including social systems like witch crazes, self-organize through

feedback loops,

in which outputs are connected to inputs, producing change in response to both (like a public-address system with feedback, or stock market booms and busts driven by flurries of buying and selling). The underlying mechanism driving a witch craze is the cycling of information through a closed system. Medieval witch crazes existed because the internal and external components of a feedback loop periodically occurred together, with deadly results. Internal components include the social control of one group of people by another, more powerful group, a prevalent feeling of loss of personal control and responsibility, and the need to place blame for misfortune elsewhere; external conditions include socioeconomic stresses, cultural and political crises, religious strife, and moral upheavals (see Macfarlane 1970; Trevor-Roper 1969). A conjuncture of such events and conditions can lead the system to self-organize, grow, reach a peak, and then collapse. A few claims of ritual abuse are fed into the system through word-of-mouth in the seventeenth century or the mass media in the twentieth. An individual is accused of being in league with the devil and denies the accusation. The denial serves as proof of guilt, as does silence or confession. Whether the defendant is being tried by the water test of the seventeenth century (if you float you are guilty, if you drown you are innocent) or in the court of public opinion today, accusation equals guilt (consider any well-publicized sexual abuse case). The feedback loop is now in place. The witch or Satanic ritual child abuser must name accomplices to the crime. The system grows in complexity as gossip or the media increase the amount and flow of information. Witch after witch is burned and abuser after abuser is jailed, until the system reaches criticality and finally collapses under changing social conditions and pressures (see figure 10). The "Phantom Gasser of Mattoon" is another classic example. The phenomenon self-organized, reached criticality, switched from a positive to a negative feedback loop, and collapsed— all in the span of two weeks.

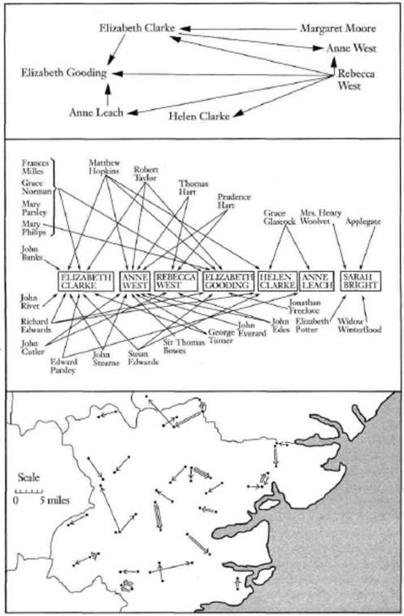

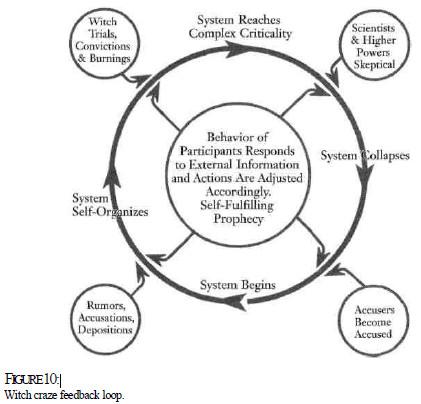

Data supporting this model exist. For example, note in figure 11 the rise and fall of accusations of witchcraft brought before the ecclesiastical courts in England from 1560 to 1620, and trace through the various parts of figure 12 the pattern of accusations in the witch craze that began in 1645 in Manningtree, England. The density of accusation drives the feedback loop to self-organize and reach criticality.

Over the past century dozens of historians, sociologists, anthropologists, and theologians proffered theories to explain the medieval witch craze phenomenon. We can dismiss up-front the theological explanation that witches really existed and the church was simply reacting to a real threat. Belief in witches existed for centuries prior to the medieval witch craze without the church embarking on mass persecutions. Secular explanations are as varied as the writer's imagination would allow. Early in this historiography, Henry Lea (1888) speculated that the craze was caused by the active imaginations of theologians, coupled with the power of the ecclesiastical establishment. More recently, Marion Starkey (1963) and John Demos (1982) have offered psychoanalytic explanations. Alan Macfarlane (1970) used copious statistics to show that scapegoating was an important element of the craze, and Robin Briggs (1996) has recently reinforced this theory by showing how ordinary people used scapegoating as a means of resolving grievances. In one of the best books on the period, Keith Thomas (1971) argues that the craze was caused by the decline of magic and the rise of large-scale, formalized religion. H. C. E. Midelfort (1972) theorizes that it was caused by interpersonal conflict within and between various villages. Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English (1973) correlated it with the suppression of midwives. Linnda Carporael (1976) attributed the craze in Salem to suggestible adolescents high on hallucinatory substances. More likely are the accounts of Wolfgang Lederer (1969), Joseph Klaits (1985), and Ann Barston (1994), which examine the hypothesis that the witch craze was a combination of misogyny and gender politics. Theories and books continue to be produced at a steady rate. Hans Sebald believes that this episode of medieval mass persecution "cannot be explained within a monocausal frame; rather the explanation most likely consists of a multivariable syndrome, in which important psychological and societal conditions are inter-meshed" (1996, p. 817). I agree, but would add that these divers socio-cultural theories can be taken to a deeper theoretical level by grafting them into the witch craze feedback loop. Theological imaginations, ecclesiastical power, scapegoating, the decline of magic, the rise of formal religion, interpersonal conflict, misogyny, gender politics, and possibly even psychedelic drugs were all, to lesser or greater degrees, components of the feedback loop. They all either fed into or out of the system, driving it forward.