Read Why was the Partridge in the Pear Tree? Online

Authors: Mark Lawson-Jones

Why was the Partridge in the Pear Tree? (14 page)

A statue of Wenceslas in Prague.

In the late ninth century, Saints Cyril and Methodius undertook missionary journeys throughout central and eastern Europe amongst the Slavic peoples. The Czech Duke Borivoy and his wife Ludmilla were converted on one of these missions although many people were opposed to the introduction of Christianity, as it threatened the ancient religion practiced in that region. The son of Borivoy and Ludmilla, Prince Vratislav, married Drahomira, the daughter of a pagan tribal chief, who held tenaciously to the ancient beliefs. Their first son, Wenceslas, was born near Prague in 907.

When Wenceslas was thirteen, his father was killed in a battle. Drahomira, his mother, took advantage of the power vacuum and religious animosity to gain support from the powerful pagan nobility whilst Wenceslas was still too young to rule. During that time, his grandmother, Ludmilla, arranged to bring him up; carefully ensuring that he kept his Christian faith, being taught by a priest who was a disciple of St Methodius. This enraged Drahomira, and she conceived a plan to murder Ludmilla, who was strangled shortly after.

Feeling herself now exempt from all Christian duty, the mother reclaimed her son. Secretly, however, Wenceslas continued to practice his Christian faith. Eventually an uprising deposed and banished Drahomira, leaving Wenceslas to take power at the age of eighteen. Wenceslas however, recalled his mother to the castle and forgave her.

There followed stories of great bravery and generosity, as Wenceslas spent much of his wealth supporting the needy in and around the city. There were also stories of miracles, where people were healed from various disabilities. The carol recounts one such incident, where Wenceslas left his bed one night and ordered his trusted knight Podiven to follow him as he delivered alms to the poor. This was a particularly foolhardy endeavour in the snow and ice. At one stage Podiven was about to give up because his feet were numb with the cold, then Wenceslas told him to walk in his footprints, which became miraculously warm. The alms were delivered and the pair returned to the castle. Wenceslas was legendary amongst his people, and considered to be a man of high integrity and morals.

However, it was his ambitious program to build churches that enraged the nobility. The troubles were soon to erupt again in earnest.

Although Wenceslas was reconciled to his mother, his younger brother Boleslas began to challenge him. The birth of Wenceslas’ first son stirred up jealousy, as succession would now pass to him rather than Boleslas. A plan was devised to kill Wenceslas after a church service, that Boleslas was certain he would attend. After the service, Boleslas followed him out and he was hacked to pieces by his servants on the steps of the cathedral.

Wenceslas was considered a saint and martyr immediately after his death, and within a few years hagiographies were written of his life. These ‘biographies’ of the saints had a huge influence of the people of the High Middle Ages. Wenceslas was used to support the belief that legitimate authority does not automatically arise from the divine right of kings, a ruler needs to be able to demonstrate that they are rex justus, a righteous king, stemming not only from great piety but princely vigour.

Referring to these hagiographies, one writer, Cosmas of Prague writing in the year 1119 agrees:

But his deeds I think you know better than I could tell you; for, as is read in his Passion, no one doubts that, rising every night from his noble bed, with bare feet and only one chamberlain, he went around to God’s churches and gave alms generously to widows, orphans, those in prison and afflicted by every difficulty, so much so that he was considered, not a prince, but the father of all the wretched.

On the question of whether Wenceslas was a duke, king or saint, the answer is that he was all three. During his lifetime he was a duke, posthumously the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I made him ‘king’. He was also canonized as a saint due to his martyr’s death, as well as for several purported miracles that occurred after his death. Wenceslas is the patron saint of the Czech people and the Czech Republic and his feast day is 28 September; in 2000 it was declared a permanent public holiday in the Czech Republic, celebrated as Czech Statehood Day.

The story doesn’t end there though, the carol ‘Good King Wenceslas’, written by the eminent English clergyman and author John Mason Neale, has a story all of its own. Neale was born in London in 1818. His father died when he was five years old. When he was fourteen he began to translate the poetical writings of Coelius Sedulius, who wrote around

AD

450, and was thought to be one of the founders of Christian hymn writing. While a student Neale developed an extraordinary interest in church archaeology, especially architecture, and with a few others founded the Cambridge Camden Society in 1839, renamed the Ecclesiological Society, which exercised an immense influence on the architecture and ritual of the English Church, which lasted till 1845.

John Mason Neale.

Neale was a great supporter of ‘Victorian Gothic’ and worked ceaselessly with those who wanted more ritual and religious decoration in churches. This movement was a natural partner to Tractarianism (The Oxford Movement) as both looked back to the Middle Ages as a time when the church met the needs of its’ parishioners both spiritually and aesthetically.

Neale graduated from Trinity College, Cambridge in 1840. He was ordained deacon in 1841 and priest in 1842. 1842 was also the year he met and married Sarah Webster. They moved to Crawley, Surrey, where he became incumbent. Ill health meant that Neale needed to resign within a few months and they went to live in Madeira.

Fortunately for Neale and hymn writing, there was a fine library at the cathedral there, from which he found sources for one of his books

History of the Eastern Church

, and also for his Commentary on the Psalms.

He returned to England in 1845, and from 1846 until his death he was Warden of Sackville College, East Grinstead, Sussex. In fact, the college was an almshouse, a charitable institution for the aged. Neale’s salary was a mere £27 a year. There he wrote furiously; history, theology, travel books, hymns, poems and books for children.

Neale continued to be a traditionalist and a staunch supporter of the Oxford Movement, this attracted criticism from many quarters, as did his outspoken views on the judgment of God that would fall on those clergy who took and destroyed consecrated property from the churches, installing ‘pews’ and other innovations. His criticism of wealthy clergy living in luxurious surroundings and his insistence on traditional church furnishings meant that for the last few years of his life he was censured by his bishop, and prevented from ministering in Church. Working closely with those who had little worldly goods in the ‘college’, supporting antiquarians who were intent on preserving the churches and continuing to act as a minister, it’s quite easy to see how Neale was drawn to the story of Good King Wenceslas.

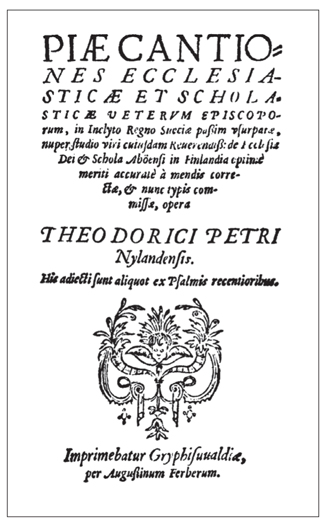

The title page of

Piae Cantiones.

Neale wrote the lyrics for ‘Good King Wenceslas’ to the tune of a thirteenth-century spring song ‘Tempus Adest Floridum’ (‘It is time for Flowering’), which was first published in the a sixteenth century Finnish collection

Piae Cantiones

. The first appearance of the carol in print was in the book

Carols for Christmastide

, which Neale published with Thomas Helmore in 1853. It is highly likely, however, that he had written the carol sometime earlier, possibly when he completed his book

Deeds of Faith

in 1849, which Neale wrote to ‘to lead children to take an interest in Ecclesiastical History’ through sixteen stories of saints and martyrs, including ‘The Legend of St. Wenceslaus’.

Neale says of Wenceslas, on his mission to the poor on the Feast of Stephen:

And so great was the virtue of this Saint of the Most High, such was the fire of love that was kindled in him, that, as he trod in those steps, [his knight Podiven] gained life and heat. He felt not the wind; he heeded not the frost; the footprints glowed as with a holy fire, and zealously he followed the King on his errand of mercy.

Perhaps Neale was drawn to the legend of Wenceslas because they shared the tragic loss of their fathers at an early age? Perhaps he saw the ‘King’ as someone who would uphold the faith in the face of trouble and conflict, as Neale felt he was doing? Whatever the reason, Neale has succeeded in his purpose, to this day people still sing of Good King Wenceslas, the unlikely hero of the poor and needy.

In the Bleak Midwinter

In the bleak midwinter

Frosty wind made moan,

Earth stood hard as iron,

Water like a stone;

Snow had fallen, snow on snow,

Snow on snow,

In the bleak midwinter,

Long ago.

Our God, heaven cannot hold him,

Nor earth sustain;

Heaven and earth shall flee away

When he comes to reign;

In the bleak midwinter

A stable place sufficed

The Lord God incarnate,

Jesus Christ.

Enough for him, whom Cherubim

Worship night and day

A breast full of milk

And a manger full of hay.

Enough for him, whom angels

Fall down before,

The ox and ass and camel

Which adore.

Angels and archangels

May have gathered there,

Cherubim and seraphim

Thronged the air;

But his mother only,

In her maiden bliss,

Worshipped the Beloved

With a kiss.

What can I give him,

Poor as I am?

If I were a shepherd

I would bring a lamb,

If I were a wise man

I would do my part,

Yet what I can I give Him

Give my heart.

Christina Georgina Rossetti was one of the most important women poets writing in the nineteenth century. Born in London on 5 December 1830 to Gabriele and Frances Polidori Rossetti, she was the fourth of five children. Her father was an Italian patriot, exiled from Naples for his political activity, and a Dante scholar who became professor of Italian at King’s College, London, in 1831. At home, Christina would have been fluent in both English and Italian. As part of the large Italian expatriate community in London, they welcomed other exiles, from Mazzini, the famous politician in exile, to chimney sweeps; and although they were certainly not wealthy, Professor Rossetti was able to support the family comfortably.