Why was the Partridge in the Pear Tree? (4 page)

Read Why was the Partridge in the Pear Tree? Online

Authors: Mark Lawson-Jones

A mixture of the Mari Lwyd and wassail customs occurs in the border town of Chepstow in South Wales, every January. A band of English wassailers meet with the local Welsh border morris side, The Widders and the Chepstow Mari Lwyd group on the bridge in Chepstow. They greet each other and exchange flags in a gesture of friendship and unity and celebrate the occasion with dance and song before performing the ‘

pwnco

’, or ‘verbal jousting’ at the doors of Chepstow Castle and several places in the lower part of the town, beginning at the Bridge Inn

and then around the town. Tim Ryan, a member of the group said, ‘It looked like they were marching to war, then all peace broke out.’ Member of the Widders ‘Mick Widder’ said it’s the ‘newest old tradition in Wales’.

In the north of England, more specifically Derbyshire, Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire, the formality of wassailing has given way to something of a phenomenon: Mass singing in the public houses during the second half of November and all of December. It has been described as one of the most remarkable instances of traditional singing in the whole of Britain.

Local people write settings for popular carols, but also the more obscure songs that have been all but forgotten. The participants attend for many reasons; some are Christians, who see this as important as any observance of Christmas held in church; some see it as an event that helps to preserve the historic singing tradition and the ancient hymns that would otherwise be out of print and out of mind; and some attend because they enjoy singing together. Whatever the reason, the pubs are usually packed with people standing with a drink in hand, to deliver their unique repertoire of Christmas songs, both sacred and irreligious, that have become an essential part of Christmas for local people and visitors alike.

In a 1978 article of the magazine

Melody Maker

a reporter travelled to South Yorkshire to experience the event in one of the ‘singing pubs’. The Royal Hotel, on the edge of Sheffield, is situated in Dungworth, a village where then ‘mostly farmers, farmers’ wives and their children live’ and the few others who made the five-mile journey into Sheffield every day.

Carols in a Derbyshire pub.

Even though Dungworth is a small village, it was reported that the people couldn’t remember a time when they didn’t spend their Sundays during the Christmas period gathering at the Royal Hotel, settling down to a pint, and then proceeding to ‘sing their heads off’

with verve and gusto. The singing started on the Sunday after Remembrance Sunday and continued until the Sunday after Boxing Day.

After the article was published in 1978, the tradition had somewhat of a resurgence, attracting fans of folk music and others who wanted to witness a living folk tradition and help to keep it alive. The influx of ‘folkies’

wasn’t wholly popular with some local people, believing that the tradition was sufficiently robust to survive on its own.

The 1978 report noted that the tradition had indeed survived in many of the ‘singing pubs’

in the area, where carols were sung with ‘no airs and graces, roared out with vigour, and at a volume that could strike terror into the hearts of neatly-surpliced choirboys with piping pure voices. Loud and lusty with no time for the sweet, lilting cadences of the carols sung at most Christmas services. The singers in the bar, shoulder to shoulder, pints in hand, mostly singing from memory.’

Singing king on a barrel.

The landlady of the Royal Hotel in the 1970s, quoted in the

Yorkshire Post

, said that they would need ‘Three eighteens for a good sing’, meaning three eighteen-gallon barrels of beer (400 pints). A regular at the carols who was also questioned about the events said, ‘Proper carolers sing and drink, sing and drink, sing and drink’, and that he felt it was ‘almost like church with good feeling and fellowship. It’s like religion with beer’.

More recently, in 2011, Dave Lambert, the current landlord of the Royal Hotel, confirmed that the tradition is still alive and well. He said, ‘Some say that carols have been sung in local pubs for the past 200 years, some say 400.’ Commenting on how unique the carols are, he said, ‘Locally, there are twenty-eight versions of “While Shepherds Watched” with a several of them being sung exclusively in The Royal Hotel with local musical arrangements that have stood the test of time’. The singing still takes place for the same amount of time, the Sunday after Remembrance until the Sunday after Boxing Day. He was also able to confirm that the consumption of beer at these unique events has not diminished either.

The carol singing

attracts upwards of 150 people, many standing outside. People travel from all over England and even further afield to witness this prime example of British culture at its best. Mr Lambert said, ‘A group of people even travelled from Norway and stayed a fortnight to enjoy the singing, they took back ideas to start the practice there’.

One feature of the Yorkshire carols that is reminiscent of the Mari Lwyd

and wassailing

is called ‘fuguing’, a verse and a response pattern of singing. Where people repeat the words at the end of the verses, and musically the bass line answers the melody. ‘Mount Moriah’, ‘Old Foster’ and ‘Egypt’ are three examples of this. Probably the most famous, however, is the musical setting written for ‘While Shepherds Watched’, which was borrowed for the folk song ‘Ilkley Moor B’aht At’.

In some pubs the words are put on a flipchart at the front, in some books are produced, but in many places the people are familiar with many words, although the more idiosyncratic Victorian lyrics continue to produce wry smiles from the assembled carolers.

In response to a suggestion that the Sheffield Carols were dying out, a contributor to an internet forum on local arts maintained that was ‘nonsense’,

stating there are still ‘over fifty versions of ‘While Shepherds Watched’ being sung throughout the region, you just have to know where to look’.

Wassailing, Mari Lwyd or Sheffield Carols are all living and breathing examples of the power of custom and culture. Keeping alive the traditions of the past, bringing people together for important celebrations.

It could have all been so different though. The Puritans had other ideas about singing, drinking, dancing and Christmas.

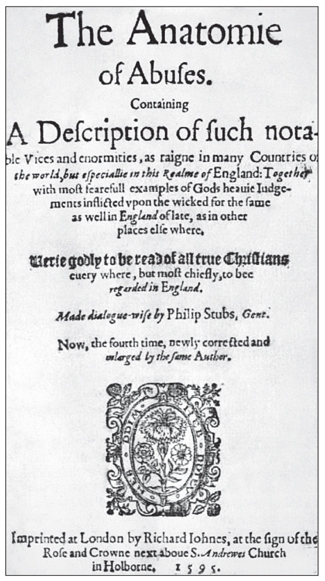

The Puritans Tried to Kill Christmas

During the sixteenth century Christmas was, as it is now, extremely popular, not only as a religious festival, but also as a time for families to take part in a wide range of traditional pastimes. Christmas music had spread from the Church, where it was found in the form of chants, litanies and hymns, to become popular songs performed throughout the land by minstrels, travelling players or wassailers, the Mari Lwyd, or just sung to simple accompaniment in pubs, houses and halls. The first Christmas carols secured the national love for them as the people danced and sang to celebrate Christmas.

The festivities saw homes and public buildings decorated with holly, ivy and rosemary. Church services were widely attended and gifts were exchanged at New Year. Seasonal food and drink would be prepared and stage-plays, concerts and events were organised for everyone. The social function of Christmas was two-fold; firstly, the struggles of a harsh winter could easily be forgotten with this welcome midwinter respite, and secondly; the Christmas season acted as a force for social cohesion, as people rediscovered their interdependence and shared the best of what they possessed. The villages and towns resonated with the sound of merriment with the accompanying stories of drunkenness and debauchery, promiscuity and other forms of excess. The success of Christmas, where the usual norms were suspended for a time of celebration, eventually became its downfall.

The Lords of Misrule.

Towns, villages, colleges and noble houses, and even the royal court often chose a mock king to preside over their Christmas festivities. Temporarily elevated from his ordinary, humble rank to that of ‘king’, he was known by a variety of names, including the Lord of Misrule, the Abbot of Unreason, the Christmas Lord, and the Master of Merry Disports. These colourful titles reflect the kind of madcap revelry associated with these parties.

The duties of the Lord of Misrule varied, as did the type of entertainment offered over the Christmas period. The Lord’s most fundamental duty, however, was to preside over the festivities as a mock king. One wealthy estate owner left a record of the authority he granted to the Lord of Misrule:

I give free leave to Owen Flood, my trumpeter, gentleman, to be Lord of Misrule of all good orders during the twelve days. And also, I give free leave to the said Owen Flood to command all and every person or persons whatsoever, as well as servants as others, to be at his command whensoever he shall sound his trumpet or music, and to do him good service, as though I were present myself, at their perils.

The Lords of Misrule presided over races through churches on hobby-horses during services, dancing through the streets and the consumption of huge amounts of food and drink. The Lord was allowed to order anyone to do anything, and at the end of the season, he was usually sacrificed ceremonially. This image of sacrificial kings who preside over debauchery is an echo of Saturnalia, the Roman festival that was undoubtedly practiced during the period of the Roman occupation.