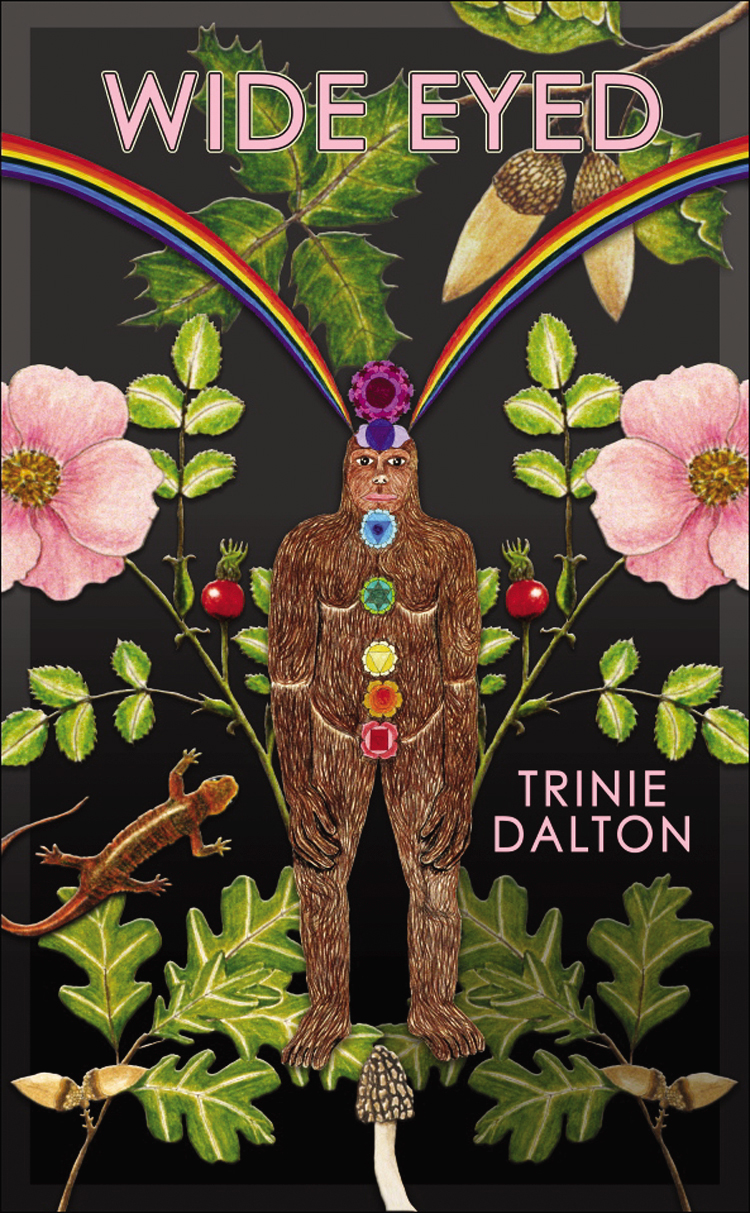

Wide Eyed

Authors: Trinie Dalton

Also from Dennis Cooper’s

Little House on the Bowery

serie

Godlike

by Richard Hell

The Fall of Heartless Horse

by Martha Kinney

Grab Bag

by Derek McCormack

Headless

by Benjamin Weissman

Victims

by Travis Jeppesen

This is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Published by Akashic Books

© 2005 Trinie Dalton

ISBN-13: 978-1-888451-86-5

eISBN-13: 978-1-617750-55-7

ISBN-10: 1-888451-86-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2005925470

All rights reserved

First printing

Printed in Canada

Some of these stories were also published in the following places:

Santa Monica Review, Purple, Textfield, Frozen Tears

(anthology),

Fishwrap, K48, Ab/Ovo

(exhibition catalogue),

Swivel, Suspect Thoughts Magazine, Bennington Review, Court Green, The Dogs

(exhibition catalogue),

Bomb, Punk Planet,

and

Lost on Purpose

(anthology).

The title “The Tide of My Mounting Sympathy” was borrowed from Wayne C. Booth’s phrase “the tide of our mounting sympathy” from his critical essay “Macbeth as Tragic Hero.”

“Extreme Sweets” borrows Laura from

The Glass Menagerie

by Tennessee Williams.

Little House on the Bowery

c/o Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

For Matt Greene

and the Daltons

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sincerest thanks to: Mike Bauer, Molly Bendall, Jesse Bransford, Sue de Beer, Martha Cooley, Roman Coppola, Sean Dungan, David Gates, Amanda Greene, David Hamma, Amy Hempel, Annie Heringer, Lisa Wagner Holley, Peter Kim, Rachel Kushner, Jill McCorkle, Casey McKinney, KC Mosso, Heidi Nelms, Shuggie, David St. John, Gail Swanlund, Johnny Temple, Andrew Tonkovich, Joel Westendorf, and Yucca.

Thanks to Benjamin Weissman and Amy Gerstler for being the ultimate teachers and friends.

Thanks to Dennis Cooper for this book.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Tide of My Mounting Sympathy

The Wookiee Saw My Nipples:

A Week in the Life of Princess Leia

A Giant Loves You

(featuring Marc Bolan)

I’d want a range life

If I could settle down.

If I could settle down,

Then I would settle down.

—Pavement

We were performing a play about this maggot on our kitchen floor who grew until he was squishing out the windows, suffocating us and all those who came into the Ranch House.

The maggot play was meant to be retro, like

Godzilla

or

King Kong

—one of those huge-creatures-dominating-humanity stories. But we were wasted on Xanax, dressed in red dresses and red feather boas, so it had a New Wave feel.

“Don’t eat me, you maggot,” I said to the two-footlong papier-mâché maggot lying on the floor.

“I vill crush you,” said Heidi, in a low, Kruschevian maggot/dictator voice from behind the door. “I am zee maggot.”

That’s the only part I remember. The script was pathetic.

Heidi, Annie, and I—roommates—renamed the

Blue

House the

Ranch

House. It was a one-story, spread out, casual Craftsman-style place.

Everything was decrepit: termites ruined the walls and vines grew in the windows. We spent our time learning Carter Family songs. Sara and Maybelle are easier to imitate than A.P.’s baritone parts. I can still play “Single Girl,” “Wandering Boy,” and “Wildwood Flower” on guitar. We had pie parties and sang to guys we invited over to eat elderberry pie hot out of the oven. The elderberries came from trees in the park because we had no money to buy grocery store ones. Countryfolk wannabes for sure.

My first night in that house I raided the basement and found a shawl, rusty tools, and knitting equipment. I had a spooky meeting with the ghost of the old lady who died there. She was making the rooms cold. Drafts of winter air were leaking through sealed windowsills even though it was summer. I told her to leave because three girls were moving in. I was alone and sensed her in the corner of the den, rocking in her invisible rocking chair. I heard the chair creaking and could smell the stale scent of the elderly. She’d died in the 1970s and no one had lived there since, the realtor told me. It made sense, then, that someone should tell her to beat it.

Back when I was nine my aunt told me that to get rid of a poltergeist, I should be firm. It really works. The Ranch House Ghost departed that night. Our theory was that she’d been buried under the avocado tree in the backyard. It had years of leaf debris piled beneath it, and grew avocados the size of cantaloupes. We figured the human compost had beefed them up. Also, next to the tree was a defunct incinerator— convenient. Her son must have folded her up, shoved her in, fired up the stove, and burned her into an ashen pile, ideal for fertilizer. That’s why our tree kicked ass.

There are a lot of ghosts and good avocado trees in The Echo Park. I didn’t know there was a “the” before Echo Park until I went to the local liquor store, House of Spirits, to get tequila for our “ranchwarming” party. I was talking to the lady behind the counter, telling her I’d just moved back into the neighborhood.

“It’s the only place I feel at home,” I said.

“So many kinds of people. Less old people now. They’re all dying,” she said.

I knew she meant the Echo Park Convalescent Home down the street, where heaps of old people roll around in wheelchairs and smell everything up. No one likes that haunted house.

The guys behind me in line started in.

“You used to live somewhere else?” one asked. He looked tight in his L.A. Dodgers cap, oversized white T-shirt, Dickies shorts, and Nike Cortez sneakers, with white tube socks pulled up over his calves. All his friends looked the same and had shaved heads.

“Yeah. But I missed stuff, like kids setting off fire-works. Or wild dogs,” I said.

“You always come back to The Echo Park,” he said. “You can’t ever leave The Echo Park.” He nodded his head at my tequila bottle.

I saw a dead body while I was living in the Ranch House. Not in the house, down a couple miles in the donut store parking lot. I was walking by, and there was yellow tape all around as if the cops thought people were going to poke the body or something. It was lying in a conspicuously contorted position, legs bent in wrong directions, neck turned too far over. Man, middle-aged. No blood. Almost like he’d been pushed out of the passenger seat by someone driving at high speed and rolled all the way into the parking lot. I associated the body with the donuts and haven’t eaten there since. After all, Ms. Donut is right around the corner. It’s the feminist donut shop.

“What kind of life would you have if you could change yours?” Heidi asked me one afternoon while she washed potatoes in the sink.

I stood leaning on the doorjamb. “A range life,” I said. That was my favorite song. I’d drink gin on the porch and listen to it. I’d gaze at the corn we planted where the lawn used to be and think about settling down. “Why?” I continued. “You sick of me? Just because I refrigerate butter?” Heidi left it out on the counter in a country-style butter dish. I hate soft, hot butter.

“Remember when the cats attacked it?” she asked. Her green gingham apron was spotted with potato bits.

It was Easter morning. We were out hunting colored eggs under the avocado tree. When we shooed the cats away, there was this little pile of butter scalloped into a pyramid shape by lick marks from their sandpapery tongues. Land O’ Lakes, unsalted—with the box where you can tear off the Indian princess and fold her knees into her chest area so she has major hooters.

There were two rules of the house: wear clothes only when necessary, and always burn candles and incense to appease spirits. Nudity made us feel closer to those in nether-regions. Bare skin seemed more ghosty. We weren’t trying to attract ghosts, but we respected them. The Old Lady Ghost was gone, but we still smelled her occasionally. I’d catch a whiff when I opened the medicine cabinet or stepped into the laundry room. She smelled like the nursing home, like musty sweaters and dirty flannel sheets. Ghosts smell pretty much the same as those about to die—which is totally separate from the way dead bodies smell. Ghosts aren’t rotten, but there is a hint of putrefaction that makes me aware of their status: not dead yet, or already dead and separated from the physical body. Why don’t ghosts smell fresh and young? Maybe old people don’t remember how they smelled as kids so neither can ghosts.

There was another old lady next door, alive but barely. She grew candy-striped beets and okra in her front yard. Yet she didn’t smell like she was dying. She prided herself on her odorless house.

“I hate bad smells,” she said as she gave the three of us a tour of her house one day. It was a Craftsmanstyle too, stained dark wood inside, black velvet curtains over the windows. The bank was threatening to take it from her. “Your house smells,” she added.

“Just that one time,” I said. Some zucchinis in the crisper had gone bad. “Myrna, what can get candle wax out of carpet?” A votive candle had burned all night, tipped over, and run between the carpet hairs in our living room.

“An iron and a dish towel,” she said. She showed us the method, making ironing movements in midair.

We fell asleep huddled on the floor around a candle because my mom called and was having visions of a murderer living next door to us, waiting to strike. My mom had psychic powers that we took pretty seriously, not seriously enough to move out that night as she had requested, but seriously enough to burn extra candles and incense, and to keep all the doors locked with the cats inside.

“Why is there so much spiritual drama here?” Annie asked that night. We listened to

Let It Bleed

by the Rolling Stones while locked in.

“Welcome to Echo Park,” Heidi said. I thought again of that old folks’ home down the block, and pictured their garden filled with car exhaust–coated agapanthus and weedy impatiens, barely tended to. The institutional garden, devoid of love.

“Do you two ever get a bad feeling when you walk past that convalescent hospital?” I asked. I kept thinking of that awful place. I took it as a sign, but I didn’t know of what.