Wild Country (31 page)

One advantage in undercover work for the Department of Justice was that, when you needed stylish cover, you could

do

it in style while Uncle Sugar paid the tab. The chief disadvantage was that, whatever your style, you could get yourself seriously killed hunting a man like Felix Sorel. Old Jim Street had told Quantrill the good news first, about the amulet and its price, then followed it with what he called AC-DC news, which might go either way.

To counter the burgeoning black market in used machinery, engine rebuild shops in SanTone Ringcity routinely checked the serial numbers of vehicle engines brought to them for repair. Since Mexico and Canada also had the capacity to build engines, they shared their solutions to the illegal machinery trade, and that sharing was so recent that its international flavor had not yet come to Sorel's attention. Now the registered owner of any vehicle from Saskatoon to San Luis Potosf was a matter of computer record. Billy Ray did not know this. He had scarcely walked out of the ringcity shop on Bandera Road before the shop foreman, having recorded the engine number, found himself staring at a blinker on his terminal screen. Blinkers meant trouble. They sometimes meant rewards, too.

In this case there was no reward, only a husky black dude in plainclothes who visited the shop immediately with an unquenchable interest about whoever had brought in that engine. Its owner of record was one Cipriano Balsas, a Mexican national. There was no report that the engine had been stolen, but Senor Balsas was linked to a known associate that set a blinker flashing in an office of the Texas Western Federal Judicial District headquarters, SanTone Ringcity. Ironically, district HQ was so near that rebuild shop that agents could see its Solarglo sign from their high windows a kilometer away.

Computers and justice departments being what they are, every name that passed through the engine ID program was also matched for whatever interest lawmen might have in certain people. Thanks to his excellent contacts, Sorel had been assured that Mexican records did not connect him with any illegal activity—nor, in fact, with any known illegals. He was not so well connected in the hated country to the north, where Sorel's name and his known associates were on record, including one Cipriano Balsas. According to the records, Senor Balsas did not draw a breath or scratch himself unless Felix Sorel told him to do so. The Department of Justice had outstanding warrants for Sorel. They were also anxious to get his finger, retinal, and tissue prints on file, on the slight chance that some government might bring enough pressure to bear so that Sorel would one day walk around loose again. Cipriano would have died rather than lead

yanquis

to his

patron

, but Cipriano did not have that choice. He had bought the van himself in Monterrey on Sorel's orders, and now the engine of that van was in SanTone. Neither Sorel nor any of his men knew it, but as far as the Department of Justice was concerned, that engine was so hot it glowed in the dark.

Because Billy Ray had not been on the wanted list, he gave his real name to the rebuild shop. And because he was an idiot, he signed the same name on the register of the No Tell Motel six blocks away. Finally, because "no tell" was a transparent lie, the register was made available to the first man flashing a federal shield on his wallet, an hour after Billy Ray signed.

So it was that Billy Ray returned from shopping with one armload of beer and the other arm full of henna redhead to find his motel room already occupied by a black agent with ball bearings for eyes and a persuasive way of displaying armament. After being read his rights Billy Ray immediately proved the fool he was by volunteering that he had been

forced

to shoot his foreman by a rancher who could neither confirm nor deny it because the back of his head had been blown away. The born-again redhead sucked on a molar, fascinated, until the federal agent decided she was guilty only of excessive availability and shooed her back onto the street again. Billy Ray, on the other hand, had earned himself an endless train of free meals and lodging at Huntsville Prison, or worse. Whisked to district headquarters, he was then advised of his wrongs, and the feds seemed to think he was important enough to string up beside his pal Felix Sorel, when they caught him—which they implied was a foregone conclusion. Briefly, Billy Ray played a delaying game.

Agents with doctorates in psychology played the man as if he were a cheap accordion, squeezing him, punching his keys as they pleased. Was Billy Ray a close confederate of Sorel? The answer was vague. Did Billy Ray know the exact whereabouts of Sorel? The answer failed to satisfy. Was Billy Ray, perchance, as queer as his buddy Sorel?

Billy Ray sang like a cageful of mockingbirds.

It soon became clear that the waddie had only the foggiest notions of Sorel's contraband, but a precise idea where that van was stashed. Golden Boy himself had run off, taking his favorites Harley Slaughter and Clyde Longo, to Little Vegas—or so Billy Ray had heard. He wasn't sure about the "little" part.

Feds conferred. The obvious answer was to turn the Nevada sin city inside out, but not so fast: there was a Las Vegas in New Mexico, too. Though not a mecca for drug dealers, the smaller Las Vegas was a place where Spanish-speaking

cimarrones

had been known to congregate. It was also within a reasonable distance of Wild Country. The town of Faro was not even real, in the sense of mayors and tax assessments. Its reality was in its gambling income and its travel connections, and one of Faro's nicknames was "Little Vegas." It was open to the public, and on a map it lay very near the spot Billy Ray had hit with a grimy fingernail, estimating the van's location. By this time. Attorney General James Street was making executive decisions on the matter.

Without knowing how many of his channels were infiltrated, but with what sounded like a monumental drug bust on tap, Jim Street picked only undercover agents under his direct control and split the ten of them up among the likely targets. Five men flew to Nevada, two to Garner Ranch, and two to northern New Mexico. Street already had his tenth man in place near Faro. He personally warned Quantrill against taking direct action unless absolutely certain of his quarry, and then only after obtaining backups. His gut feeling, Street confided, was that Sorel and his men would head for New Mexico. Once positively identified, they could be quietly surrounded by local, state, and federal authorities. Street's last advice was to remember that Felix Sorel was a sidewinder. In Wild Country that meant the man was fast, deadly, aggressive, and would give no warning before he struck. This was no epithet to Quantrill, who had once been a government-run sidewinder himself.

Quantrill rented a gleaming new hovercycle, a Curran with all the comforts of home, and using the credit code number assigned to "Sam Coulter" by Street, obtained a pocketful of crisp new bills from the main hunt lodge. Less than an hour after his scrambled call, wearing his best casual western outfit with the Chiller snugged into his armpit. Ted Quantrill topped a gentle rise and scanned the town of Faro.

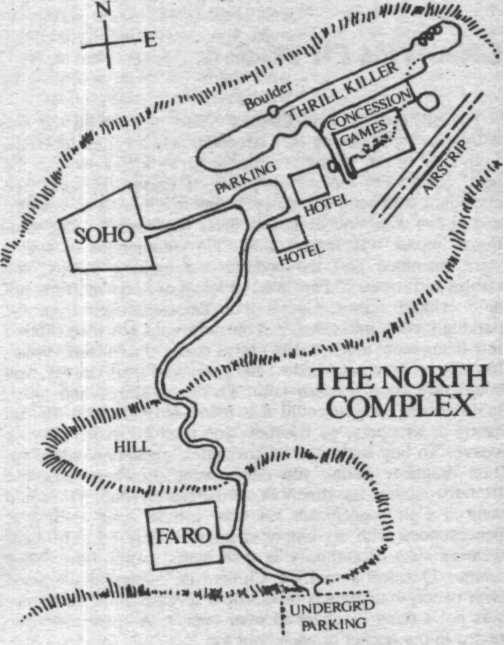

The planners of Wild Country Safari had chosen the site with great care, placing Faro deceptively in a valley separated from sight of the Thrillkiller complex, two klicks away in the next valley. On topping that rise, a visitor saw only the clapboard structures and dusty streets of a frontier township, and guests were encouraged to dress appropriately. Its emotional impact was instant 1885. No automobiles or cycles were permitted past the underground parking facility; the stables and streets of Faro were redolent of horse muffins, not auto exhaust fumes. Guests rode the stagecoach from the parking facility into town, and the cavernous gift shop offered few items more modem than cactus candy. From clerks wearing gaiters, green eyeshades, and garters on their sleeves, you could buy good western garb, Pendleton shirts, and hand-tooled boots, or you could rent them. No beer in bulbs, no candy in wrappers, no Kleenex; you used a kerchief or your sleeve. To buy such stuff as cosmetics, cigarettes, and common drugstore items, you either went elsewhere or chose from the modest assortment at the mercantile shop. You could wear a Colt peacemaker on your hip so long as it was peacebonded with six empty chambers. Only security men, wearing stars of authority in their shirts, were allowed live ammo. Quantrill's muffled Chiller, its magazine crammed with twenty-four rounds of flashless seven-millimeter ammo, was not a thing he chose to wear openly. A spare magazine rested in the pocket of each boot top.

The memory of San Antonio Rose had been flawless. Faro's last chance to take a guest's money was the small, too neat Last Chance Saloon, nearest to the parking facility. Three blocks away across the tic-tac-toe street plan, on the way to the next valley, lay the Early Bird Saloon. The Long Branch occupied the entire center block of Faro, a shingled roof running completely around the building over its broad wooden porch. The many upstairs windows suggested dozens of sleeping rooms, and it was said that you could get your wick trimmed in some of those rooms by petticoated ladies.

It was also said that the meals at the Long Branch could, if you spent much time there, make you as fat as a forty-pound robin. The dinner fare ran to corn on the cob, succulent steaks the diameter of cantaloupe and almost as thick, sourdough biscuits with redeye gravy, and buttermilk in heavy pitchers. Some subtle manager had discovered that a meal like that could give casual gamblers a stronger sense of well-being than three shots of Old Sunny Brook.

Faro's staff spared no effort in keeping the place authentic, including the consumption of coal oil for lamps. The whole town exuded a faint odor of the stuff, reminiscent of diesel fuel and, along with wandering scorpions and rattlers, among the few real dangers in town. Faro's buried water mains were pressure-fed from a more modern installation, a valley and a century removed.

That modem complex lay sequestered in its own long valley, the two hotels and the clinic set mostly underground with huge central atriums like sinkholes walled with glass. At one end of the valley was a romantic, stuffy jumble of structures dubbed "Soho," five hundred meters square, built to resemble downtown London during the Battle of Britain in the year 1941. Its streets, hardly more than alleyways, were mostly cobbled, the buildings sprayed for the look of stone under a coal-smoke patina. Many of the upper windows were broken as if by concussion, some with proper little curtains sadly waving from them like forgotten flags of truce. Visitors entered and left Soho from only one street, Brewer, and were prevented from other exits—and from loss of the illusion—by blockades. Beyond the cordons one could see signs reading "UXB," suggesting an unexploded Nazi bomb, and rubble choking the streets with the acrid tang of cordite turning like knives in the nostrils. Now and then, from behind the barricades at a safe distance, one might see a hunk of masonry, topple from a cornice into the street below.

During daylight hours, Soho's guests could see music hall hijinks or an Agatha Christie play enacted by androids who never fluffed a line and, in a distinct improvement over live actors, gauged their curtain calls to the amount of applause. Or they could buy Harris tweeds, spats, or bowler hats in Soho's shops; devour steak and kidney pie until gout set in; get laid standing up by a delicious android with Eliza Doolittle's own accent and no compunctions about copping a feel; or get viciously insulted in a small philatelist's shop. All in all, patrons of Soho thought a hundred dollars a day was very reasonable for the experience, especially since it included a night's lodging—not that anybody got to sleep much. For one thing, there were the regular percussive announcements by an unseen Big Ben, which began each brief concerto with a catastrophic clatter as if someone were using its gears to grind plate-glass windows. It wasn't precisely authentic, but it added its own brand of charm. And then, of course, there was a good, safe war.

The main show was the London blitz, three nights a week, and it was a multimedia sensation to send the craven sprinting down Brewer Street for the exit. Two WCS pilots of Confederate Air Force vintage flew the pair of half-scale, twin-engined Heinkel bombers, which were invariably picked out by searchlights to reveal the swastikas gleaming on their skins. Because a scaled-down Beaufighter was murderously hard to fly and Hurricanes lacked pizazz, other pilots chased the Heinkels in five-eighths-scale Supermarine Spitfires. Particularly on moonlit evenings, the low moan of sirens, the drone of Heinkels, the hackle-raising howl of Spits in pursuit, and the hammer of distant machine-gun fire made you suspect a time warp. The dopplering whistle of bombs and the concussions made you damn near sure of it. The choreographed march of low-level pyrotechnic flak bursts and the "crash" of a Heinkel just out of sight, complete with fireball, compelled belief.

This kind of mock-up war was expensive, and much of its timing depended on computers. The hidden kilowatt-rated loudspeakers and pyrotechnic machines were so well placed that few people suspected the aircraft were scaled down, flying rather slowly and so low that only an occasional searchlight beam could be seen from Faro. The concussions, when anyone in Faro asked, were said to be blasting operations in a distant mine. In daylight, all this carefully staged flummery would not have fooled a real Londoner for a second, but at night Soho gave added spice to drinking tepid bitter beer in basement pubs or making love in a blacked-out upstairs room. For its sky-high rates, Soho got an astonishing amount of repeat business.